Patent Models, War, and Poets, 1829–1865

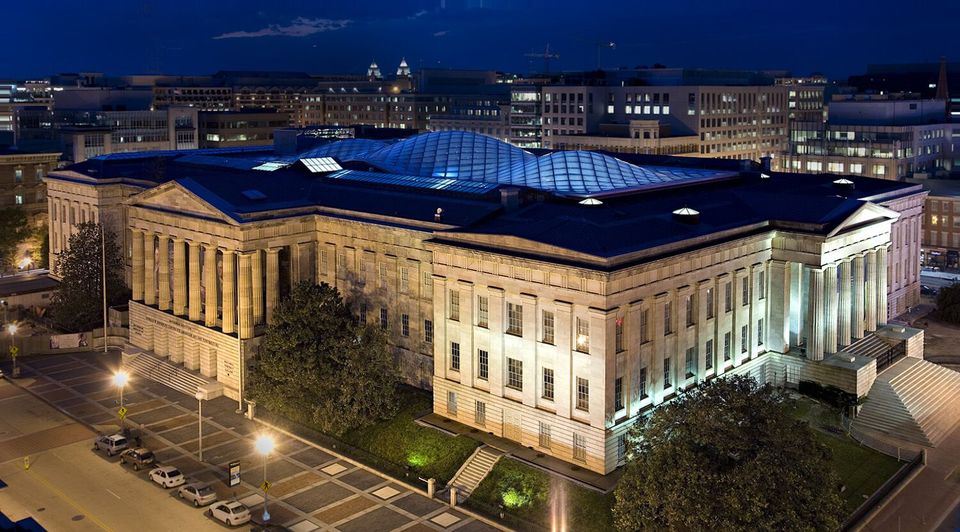

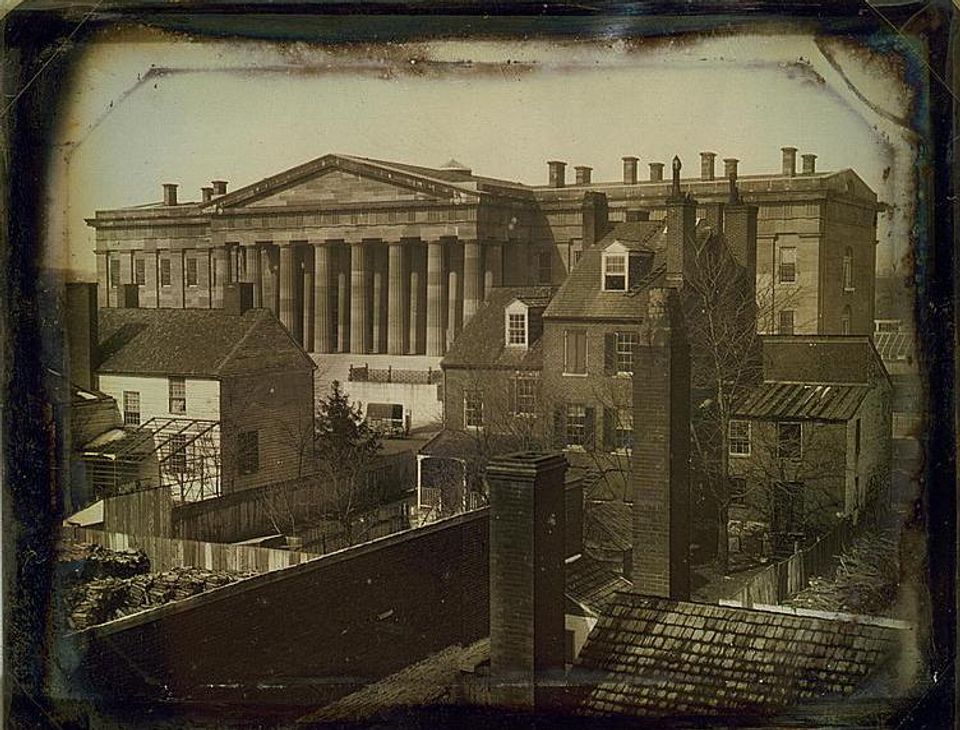

Praised by Walt Whitman as “that noblest of Washington buildings,” the former Patent Office building in the nation’s capital, has been SAAM’s home for nearly fifty years. Considered one of the finest examples of Greek Revival architecture in the United States, the building was designed by several prominent architects of the day, including Robert Mills (1781-1855), then architect of public buildings. Begun in 1836 and completed in 1868, it is one of the oldest public buildings constructed in early Washington, and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Pierre L’Enfant’s original plan for the capital included a designated site, at 8th and F streets N.W., for a national, nondenominational church or pantheon for the nation’s heroes. On July 4, 1836, President Andrew Jackson authorized the construction of a fireproof patent office. The building was designed to celebrate American invention, technical ingenuity, and the scientific advancements that the patent process represents.

Under the direction of Mills, the south wing was begun in 1836. Mills is credited with many of the building’s structural innovations, such as the brick vaults and solid masonry construction, and graceful details, such as the curved double staircase and the soaring, light-filled Lincoln Gallery, now a showcase for SAAM's contemporary artworks.

The Patent Office moved into the south wing in 1840; it was completed two years later. The building was always intended for public display of patent models that were submitted by inventors. In addition to the models, the government’s historical, scientific and art collections, including the Declaration of Independence and George Washington’s Revolutionary War camp tent, were exhibited on the third floor.

From 1849 to 1855, work continued on the east wing that was initially overseen by Robert Mills, who was replaced in 1851 by Thomas U. Walter, architect of the Capitol. This wing is the only portion of the building that remains today as originally built. Construction followed on the west wing (1852–1857) and the north wing (1856–1868).

From 1849 to 1917, the building also housed various bureaus of the Department of the Interior. During the Civil War, it was used as a barracks and military hospital, where both Walt Whitman and Clara Barton cared for the wounded soldiers. In March 1865, it was the site of President Abraham Lincoln’s inaugural ball. A fire in 1877 badly damaged the upper floors of the north and west wings, and much of the third floor was restored by Adolf Cluss in the popular ornamented Victorian style of the time.

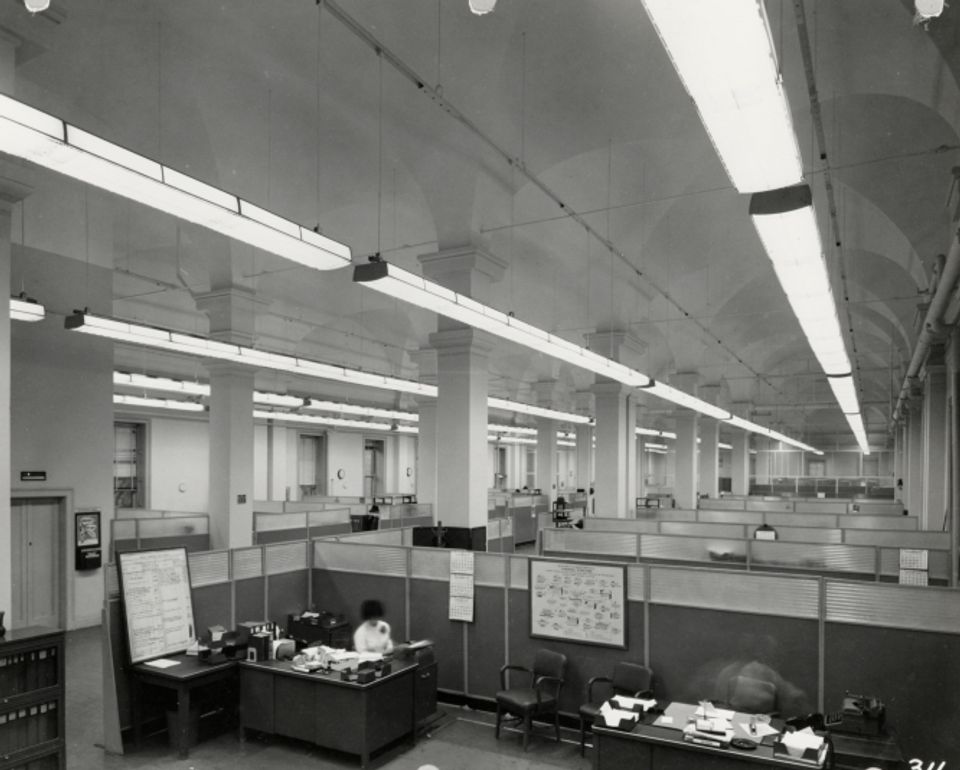

Challenges and Triumphs, 1932-1968

After the Patent Office moved out of the building in 1932, the Civil Service Commission occupied offices in the building. In the 1950s, the building was scheduled for demolition, but the nascent historic preservation movement championed its cause and eventually convinced President Dwight D. Eisenhower to spare it in 1955. Congress then transferred it to the Smithsonian in 1958 for use as a permanent home for the Smithsonian American Art Museum and the National Portrait Gallery. In 1965, it is designated a National Historic Landmark. After an extensive renovation (1964-1968), the building opened to the public as Smithsonian museums in January 1968.

To learn more about this period, see Plans for a Permanent Home

A Museum for the Twenty-first Century, 1990-2006

In the 1990s, the Smithsonian embarked on a plan to restore the building, and to create innovative new public facilities through a public-private partnership. The renovation took place from 2000 to 2006, and revealed the building’s exceptional architectural features, such as the porticos modeled after the Parthenon in Athens, a curving double staircase, colonnades, vaulted galleries, large windows, and skylights as long as a city block. New preservation technologies and the re-use of historic materials aided in the building's restoration.

In addition, two innovative and new public spaces opened to museum visitors in 2006: the Lunder Conservation Center and the Luce Foundation Center for American Art. The Nan Tucker McEvoy Auditorium and the Robert and Arlene Kogod Courtyard also comprised major enhancements that make this a destination museum for the 21st century.