Curator Melissa Ho reflects on what drew her to the subject matter for her upcoming exhibition exploring how American artists responded to the turbulence of the Vietnam War.

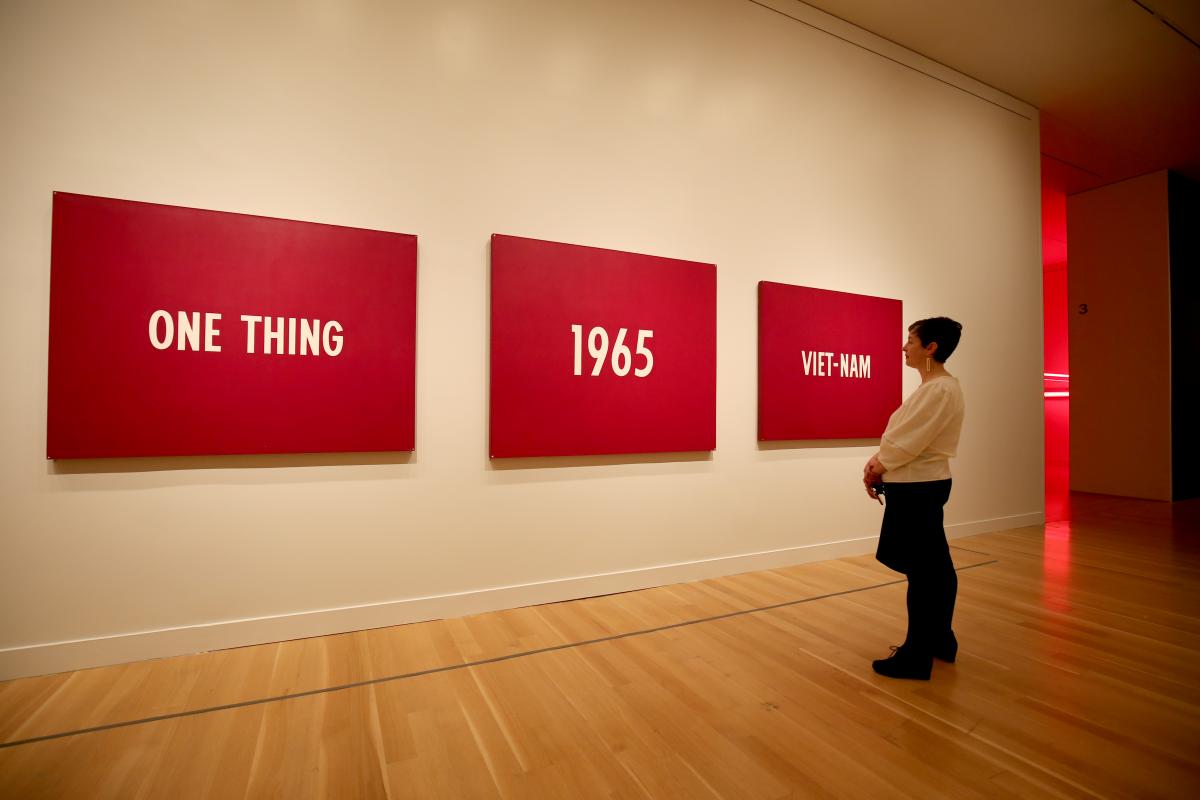

When I first encountered On Kawara’sTitle nearly ten years ago, I had never seen a photograph of the painting or heard of its existence. The work hung by itself, highlighted on an oversized wall at the entrance to the National Gallery of Art’s display of modern and contemporary art. Title consists of three canvases, each a field of deep magenta punctuated by neatly lettered white text and—upon close inspection—tiny adhesive stars, one adorning each corner. Taken in at a glance, the words ONE THING / 1965 / VIET-NAM are immediately striking.

Created the year after Kawara settled in New York, Title was a breakthrough for the Japanese-born artist. It marked a turning point in his practice, initiating an engagement with time as subject matter that he pursued for the rest of his life. Following the triptych, Kawara embarked on his Today series of date paintings; he completed his last, of hundreds, in 2013. Each of these works records the date of its making on a monochromatic ground of gray, red, or blue and is free of overt emotional or topical content. The carefully rendered works refer again and again to “today,” conveying the shape and experience of time, how it cycles and accumulates, more than imparting the particulars of any historical moment.

Title, however, is endowed with powerfully specific connotations. Unique within Kawara’s oeuvre, it names a place, “VIET-NAM,” in combination with the year it was made, “1965.” In 1965—and still for many Americans even today—the country of Vietnam was associated with one thing only: war. For the Vietnamese, the war being waged there was both a complex civil conflict and a chapter in a much longer history of armed struggle against foreign domination, fought previously against the Chinese, the Japanese, and the French. For Americans, 1965 ushered in a new phase in the fight against communist North Vietnam, which the United States had been involved in since the early 1950s. After years of providing massive economic and military support, first to France and subsequently to the state of South Vietnam, the United States took the consequential step of committing ground troops to the south and beginning a bombing campaign against the north.

At the time he created Title, Kawara could not have guessed that the war in Vietnam would continue another ten years, claiming millions of lives and resulting in a mass migration of refugees from Southeast Asia. Yet he understood enough of the human and geopolitical stakes to employ the words “ONE THING,” a phrase that seems to anticipate the overwhelming presence the Vietnam War would soon have in the public consciousness. As the war widened and casualties mounted, more observers in the United States would become alarmed by developments in Southeast Asia. That Kawara was already alert to the trauma unfolding there is perhaps unsurprising; he had direct experience of war—and of the force of U.S. military power—having been a twelve-year-old in Japan when atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The brushwork in Title is uninflected and tidy. Yet the painting, through its understatement, broadcasts a strong sense of moral urgency. Kawara is well-known for his reticence. For most of his career—in fact, since 1965—he refused to grant interviews or make public statements. That such a self-effacing, reserved artist created a painting that so pointedly references a current event seemed to me remarkable upon first sight. It was evidence of how intensely the war in Vietnam was experienced even from afar. And it made me wonder, were there other unexpected traces of the Vietnam War to be found in the art of its time?

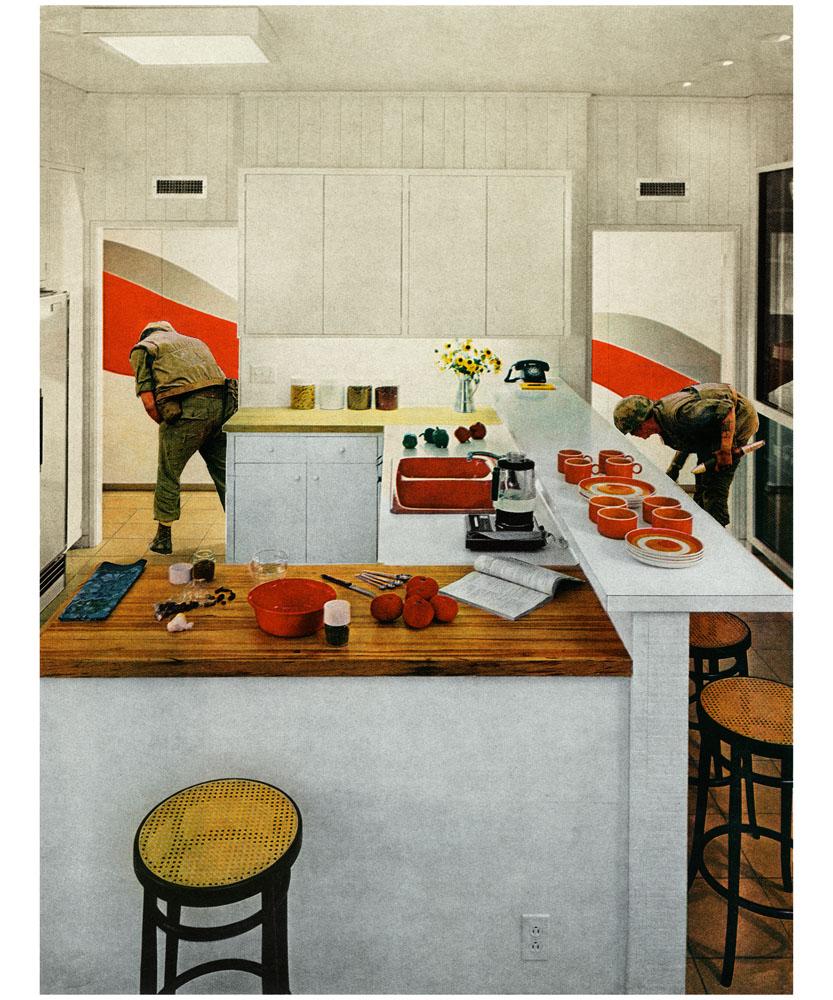

The 1960s had begun dominated by American art movements considered cool and autonomous. It ended with a small but influential wave of artists choosing to engage—with their present moment, with politics, and with the public sphere. Though far from the only social factor, America’s war in Vietnam profoundly influenced this shift from ideals of aesthetic purity toward a realm of shared conscience and civic action. Due to the military draft, unprecedented media coverage of combat, and mounting evidence of a “credibility gap” in the government’s account of events, the Vietnam War had pervasive impact. Indeed, by the late 1960s, the war loomed, for many Americans, as the “one thing.” Among visual artists, there was no consensus about how best to address the war through art, or even whether this was an appropriate goal. Some sought in their work to raise political consciousness about the Vietnam War and thus, it was hoped, to help end it. Many others, while not explicitly activist in their practice, produced work steeped in the iconography and emotions of the conflict.

As we trace how the effects of the war interacted with broader developments in American art between 1965 and 1975, we see a revival of openly affective imagery, a widespread preoccupation with the body and its vulnerability, and an embrace of facts or information as material for art. New artistic genres, all oriented toward narrowing the gap between art and life, emerged—such as body art, institutional critique, documentary art. So too did an ever greater range of artistic voices, as people of color and women demanded to have their perspectives on the war heard.

This essay is an excerpt from the exhibition catalogue, published by the Smithsonian American Art Museum in association with Princeton University Press. The catalogue and exhibition bring together both well-known and rarely discussed works, making vivid an era in which artists endeavored to respond to the turbulent times and openly questioned issues central to American civil life.

Artists Respond: American Art and the Vietnam War, 1965-1975, brings together nearly 100 works by fifty-eight of the most visionary and provocative artists and artist groups of the period, including Asco, Corita Kent, Edward Kienholz, Rupert García, Leon Golub, Hans Haacke, David Hammons, Kim Jones, Yoko Ono, Martha Rosler, Carolee Schneemann and Nancy Spero. Galvanized by the moral urgency of the Vietnam War, these artists reimagined the goals and uses of art, affecting developments in multiple movements and media: painting, sculpture, printmaking, performance and body art, installation, documentary art, and conceptualism.

Artists Respond is presented in conjunction with an installation by internationally acclaimed artist Tiffany Chung. Tiffany Chung: Vietnam, Past is Prologue, which also opens on March 15, probes the legacies of the Vietnam War and its aftermath through maps, videos, and paintings that highlight the voices and stories of former Vietnamese refugees.

On Friday, March 15, from 9 a.m. to 5:30 p.m., join us for a day of discussions and lectures on topics related to Artists Respond. The morning session features a group of distinguished scholars who provide insights into how artists of the Vietnam War era sought to engage. In the afternoon, artists whose works are in the exhibition—including Rupert García, Hans Haacke, and Martha Rosler—address their varied experiences of the war period. More information, including the conference program, webcast link, and speakers bios, can be found on the symposium page.