In 2021, SAAM filled a major gap in the museum’s collection of modern and contemporary art when we acquired three works by the acclaimed painter Kay WalkingStick: Two Women II (1973), With Love to Marsden (1995) and Orilla Verde at the Rio Grande (2012). These three paintings reflect the variety and complexity of WalkingStick’s practice and demonstrate how she has been a part of the fabric of American art for more than fifty years. All three come directly to the museum from the artist.

WalkingStick, a citizen of the Cherokee Nation, first began exhibiting in the late 1960s and is still creating new artworks today. She is celebrated for her powerful landscape paintings, which imbue depictions of place with spiritual significance and cultural memory.

WalkingStick’s work has moved through many phases. Over her multi-decade career, she has engaged with Native history, feminism, minimalism, and other key artistic movements. What has remained constant is her deep dedication to the practice of painting; an abiding interest in exploring, through this medium, the power of embodied and spiritual experience—in particular, in relation to place.

WalkingStick created Two Women II when she was in her thirties. She had married soon after graduating from college in 1959 with a degree in painting, and she and her husband quickly started a family. But despite moving from New York City to the New Jersey suburbs and the demands of raising two young children while her husband commuted into the city for work, WalkingStick never wavered in her identity or determination as an artist. She remained plugged in to the happenings and ideas of the art world, and in her home studio, she made a remarkable body of hard-edged figural paintings.

These bright acrylic paintings combine the smooth, alluring surfaces and exacting execution of an abstract painter like Ellsworth Kelly with the candy colors and vivid effects of pop art. The subject matter is figural and notably sensual. Produced against the cultural backdrop of the sexual revolution, the works celebrate bodily ease and pleasure among both women and men, using a visual language of simplified planar forms.

WalkingStick had first been inspired to take this approach when she observed her cast shadow while walking on the beach – she was struck by how her shadow was an abstract yet utterly recognizable version of herself. In Two Women II, she depicts two figures—one at bottom in bright green, the other above and to the left in tangerine orange—both unselfconsciously nude. With legs bent, feet touching, they seem to relax on the floor and mirror one another in their poses. This is an especially playful work, with many non-systematic color choices and shapes enlivening the composition beyond the two women. As the artist put it to me, she wanted to “jazz” the colors—to activate their relationships—as much as possible.

WalkingStick also described this painting to me as a joyful declaration of female autonomy. It reflects a breakthrough moment when feminist artists were endeavoring to make works expressly from and about a woman’s point of view. In WalkingStick’s case, as a painter, she was knowingly working in counterpoint to the long history of male painters regarding and depicting the female nude.

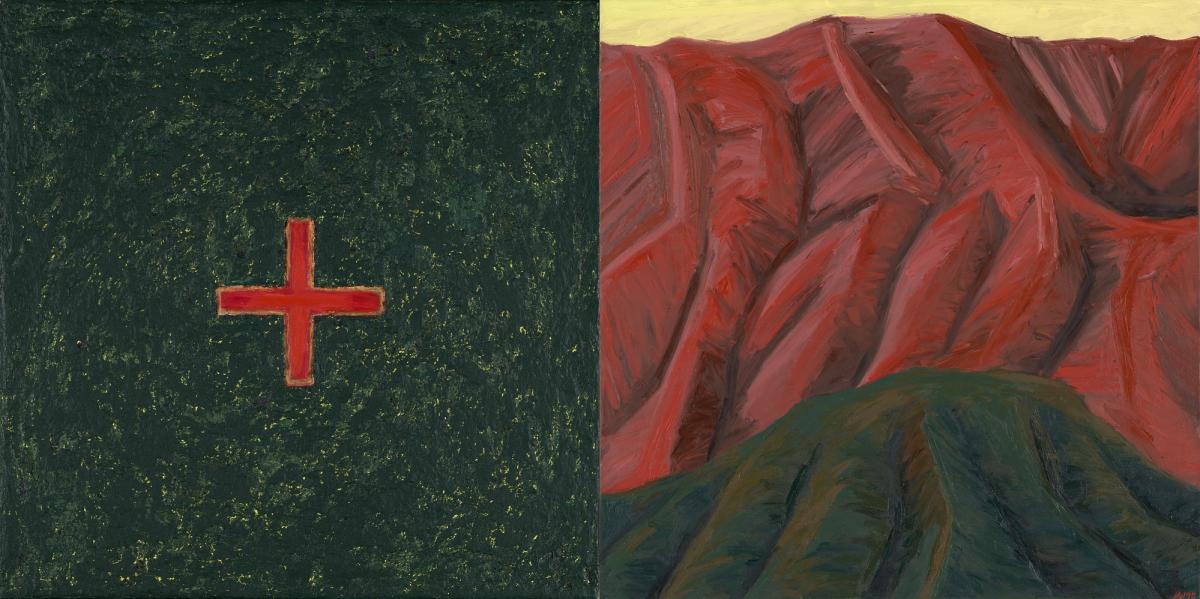

The second work, With Love to Marsden, was created twenty years after Two Women II. By this time, WalkingStick was a nationally recognized artist and a tenured professor at Cornell University. It was in fact diptych paintings like this one that earned WalkingStick widespread critical attention beginning in the mid-1980s, and they remain among her most celebrated bodies of work. Walkingstick painted With Love to Marsden when she was an artist-in-residence at the Heard Museum in Phoenix, Arizona, where she was inspired by the features of the land.

The title refers to the great early American modernist painter, Marsden Hartley who also painted the U.S. southwest, as well as Mexico. The painting consists of two square canvases put side by side, showing two representations of the same place. WalkingStick uses this paired format to propose an inextricable relationship not just between abstraction and representation, but between spirit and matter; the eternal and the temporal; between what is felt and what can be seen; between the soul and the body. The left-hand canvas features an equilateral cross, a symbol WalkingStick has featured in many works because it can be read in multiple ways: such as a reference to Native American belief systems invoking the Four Directions or as a reference to the Christian cross.

Orilla Verde at the Rio Grande continues WalkingStick’s fascination with the format of two panels and with the landscape form. In these more recent works, she creates images that span the two sides – and they are unabashedly beautiful and reverent.

The creative process behind these landscape paintings is two-fold. First, WalkingStick seeks out landscapes that inspire her, spending time in different locations across the country – in this case, in the Orilla Verde area along the banks of the Rio Grande River and within the steep-walled Rio Grande Gorge in New Mexico. She wants the paintings to relate directly to specific and recognizable locations, so while on site, she fills notebooks with sketches and takes photographs. Second, she researches the Native history and art of the places that she paints. In this case she found in the collection of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian, several Ancestral Pueblo pots that were collected at the turn of the twentieth century and which originate from around the same area along the Rio Grande.

From this research, she creates the one element of abstraction that persists in her landscape works. Her final touch on each piece is to stencil an Indigenous pattern—borrowed, in this case, from the Ancestral Pueblo pots—across the surface of the canvas, literally marking the depicted land as Native land. It is a declaration of Indigenous presence and persistence.

This assertion of Indigeneity is all the more welcome and significant within an American art collection such as SAAM’s that includes many paintings representing the European American landscape painting tradition—a tradition that has historically denied the presence of Native people.