When the landmark exhibition Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists opened at the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s Renwick Gallery in February 2020, the exhibition featured a ceramic sculpture by Christine Nofchissey McHorse (Navajo), Robster Claw (2016), a black shimmering sculpture with a twisted base and a spiky pinnacle “claw” that folds back into itself. Her ochre-colored Lizard Pot (ca. 1990) also was on public display in the permanent collection galleries. The reunion of the two artworks demonstrated the tremendous range in McHorse’s art over time and her inclusion in Hearts of Our People as a leading force in ceramics.

Over the course of her more than fifty-year career, McHorse continually experimented with designs, materials, and firing techniques. During an interview she explained, “To me, it is all about change…if you are set and rigid, you can’t bend.” Her dynamic and experimental artworks exhibit that philosophy of embracing adaptation and metamorphosis.

On February 17, 2021, devastating news reached across the Native American art world and among ceramic circles; McHorse passed away from complications due to COVID-19 at the age of 72. Garth Clark, art historian and her gallerist, reflected, “Her forms were unprecedented; complex, architectonic volumes that interlocked to create totemic vessels. Her art had as much to do with Constantin Brâncuși, Jean Arp, and Antonio Gaudí as they had to do with Native American pottery.”

Born in Morenci, Arizona, in 1948, McHorse was the fifth of nine children born to Mark and Ethel Yazzie Nofchissey. During the summers she traveled away from the mining town to visit with her grandmother, a weaver and a skilled horsewoman, on the Navajo reservation. In the tenth grade, she entered the Institute of American Indian Arts, an art school for Native students in New Mexico. McHorse took courses in silverwork, foundry arts, painting, and design but “always gravitated back to the clay.”

McHorse spent time with her husband’s grandmother, Lena Archuleta, a Taos potter. Archuleta saw that her daughter-in-law had a talent for ceramics and instructed her in Pueblo pottery using micaceous clay, a local clay that shimmers due to the high mica content. She taught McHorse to gather and process clay, coil build, burnish, and pit fire. First, McHorse created clay figurines and then cooking pots before shifting to thinner walled, decorative ceramics. As she told a reporter, “my pottery got a little bigger, a little better. The types of pottery I did grew. And then I started trying different styles, different techniques of building.” McHorse also conducted research on Navajo pottery with its use of piñon tree pitch on the surface as a natural lacquer and waterproofing sealant. She incorporated various ceramic techniques and materials to create her signature work.

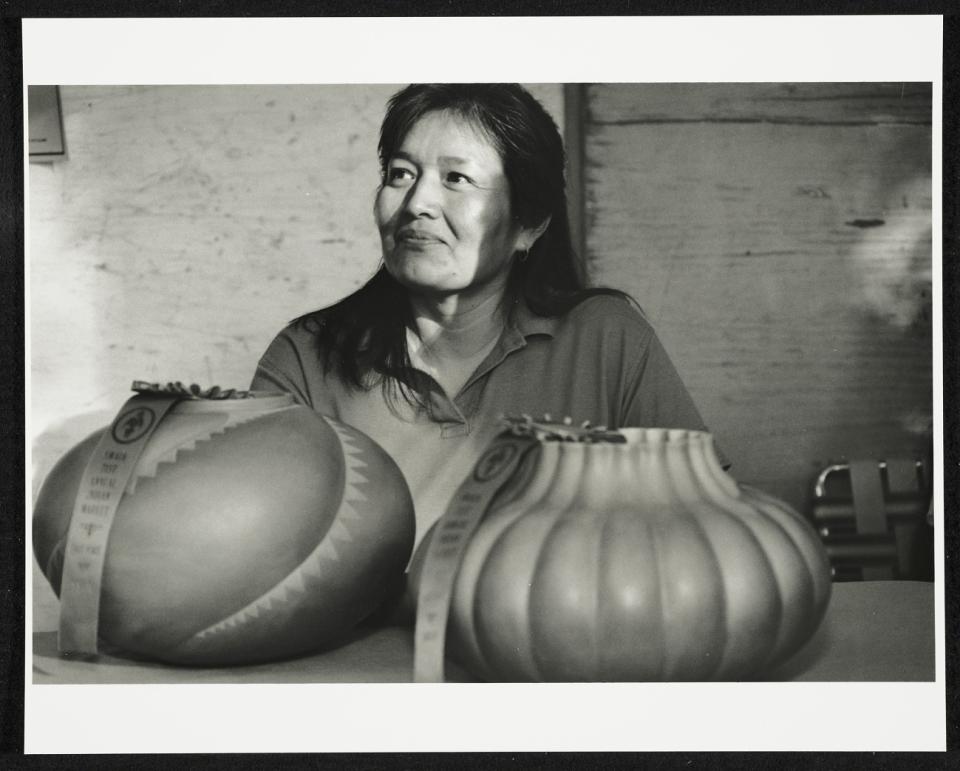

The Smithsonian American Art Museum’s collection features three works by McHorse—all partial gifts from the prominent folk art collectors Chuck and Jan Rosenak—that date from 1988 to 1991 and represent McHorse’s Pueblo and Navajo hybrid pieces. Wolves Courting at Full Moon (1988) is a highly polished globular pot made from micaceous clay and then covered in piñon pitch. She added a scene of two wolves chasing each other around the moonlike rim.

Lizard Pot, is also made from micaceous clay and then covered in piñon pitch. Instead of a continuous rim, McHorse carved out step designs and added lizards on two sides, evoking lizards climbing on an adobe building. The interior of the pot is highly polished and reveals a warm ochre color.

Crow Pot (1991), uses micaceous clay and piñon pitch as well. The pot has a long neck with a base in the shape of a pumpkin or gourd. The neck contains a wraparound scene of a crow in a corn field with rain designs at the top. While the crow is in black, the rest of the pot is in an autumnal butternut squash color.

McHorse commented that she could look into the clouds or across the land and a piece of pottery would come into her mind. Likewise, she said, “There’s a period where I gain as much of the craft as I can, and then I start exploring structure — how far I can push the shape or how much extension I can get without losing the strength of the clay.” She continued to be innovative and test what the clay could do. During this time, McHorse had been selling her art at the Santa Fe Indian Market, an annual art market that brings millions of visitors and collectors to New Mexico. She also exhibited at other art markets and museums in the Southwest, such as the Inter-tribal Indian Ceremonial in Gallup. McHorse participated at the Santa Fe Indian Market until 2005, receiving a total of thirty-eight awards over twenty-three years.

In 2002, McHorse’s work was included in the Changing Hands: Art Without Reservation, Contemporary Native American Art from the Southwest exhibition at the American Craft Museum (now the Museum of Arts and Design) in New York. Gallerists Garth Clark and Mark Del Vecchio noticed her ceramic pieces in the show and remarked, “they were among the freshest and most exciting contemporary ceramics we had seen in years.” Clark and Del Vecchio contacted McHorse and then carried her art in their galleries and in shows across the globe. McHorse was the subject of a solo exhibition, Dark Light: The Ceramics of Christine Nofchissey McHorse, that toured from 2013 to 2015 to numerous locations including Houston, Kansas City, Norman (Oklahoma), Santa Fe, and the Navajo Nation. “Dark Light” was the title of an ongoing series of her black micaceous works built into highly architectural forms, like Robster Claw.

Ceramicist Jane Osti (Cherokee Nation), whose Tall Squash Pot (2020) was acquired by the Smithsonian American Art Museum last year, reflected that, “Her art was so wonderful, just exquisite, and she spoke about it so eloquently and with such ease…Her beauty and the beauty of her work will live on in my heart and mind. She was truly a creative genius.”