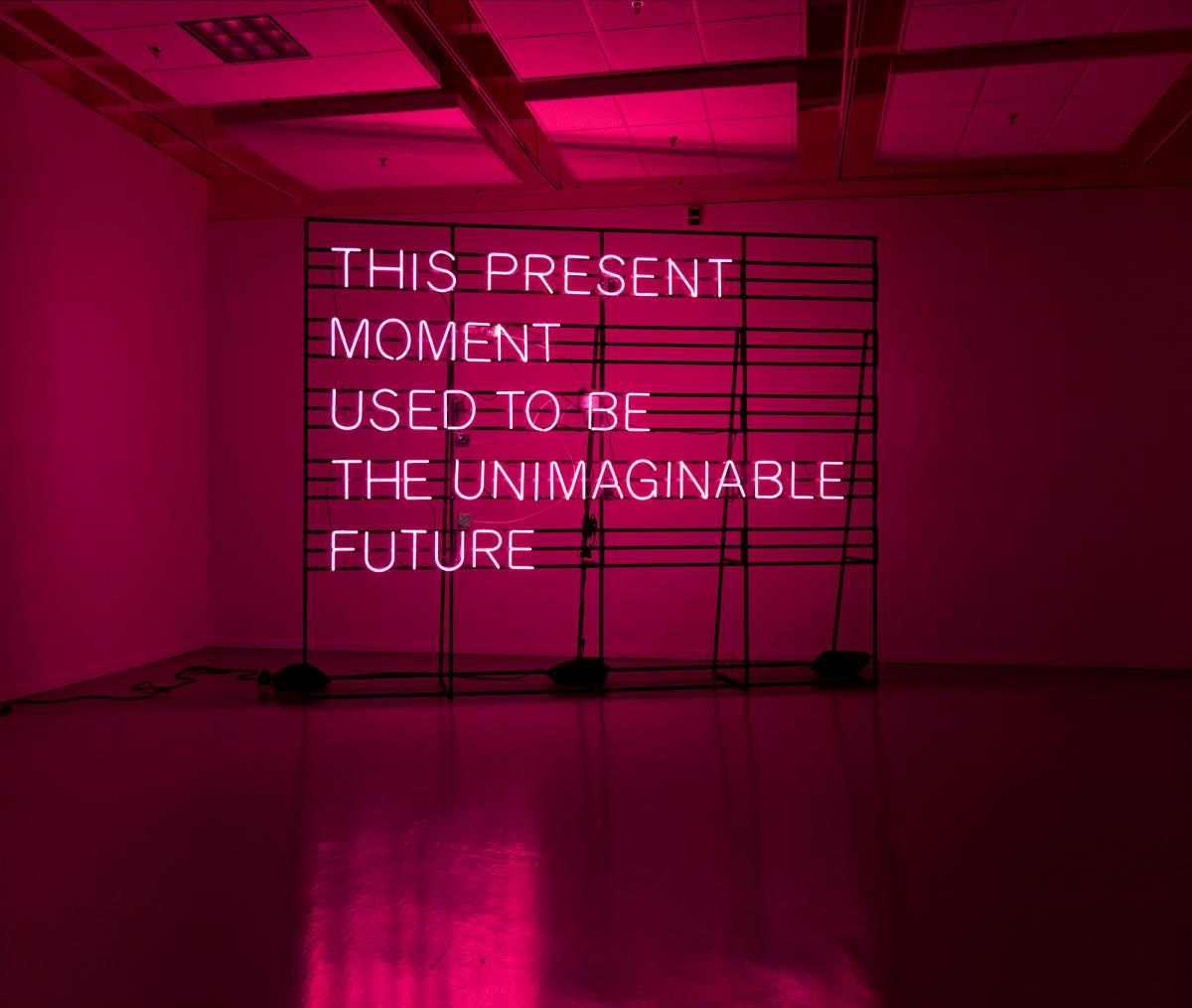

Sculptor Alicia Eggert creates immersive artworks that examine the significance of language and time and how these two powerful, yet invisible, forces shape our perception of reality.

Her neon billboard This Present Moment (2019-2020) is in SAAM’s permanent collection. The artwork, based on a quote from the revolutionary futurist Stewart Brand’s book, The Clock of the Long Now (1999), inspired the title of the exhibition This Present Moment: Crafting a Better World.

“This present moment

Used to be

The unimaginable future.”

— Stewart Brand, The Clock of the Long Now

The quote serves as a manifesto for living intentionally, prompting viewers to become more present and consider our impact on the future. Eggert also adds additional significance to her monumental work by utilizing pink neon, a call out to the #MeToo movement against sexual abuse and harassment.

In the exhibition catalogue for This Present Moment, Alicia Eggert shared her thoughts on the power of the past, present, and “unimaginable future.”

In the summer of 2019, I visited the site of Hutton’s Unconformity at Siccar Point in Scotland. I hiked across a green pasture and down a steep hill to a rocky promontory that is considered the birthplace of modern geology. On that promontory in 1788, James Hutton noticed small ripple marks in the stone that represented a distant moment in history, when that spot was at the bottom of the sea. In Hutton’s time, it was commonly believed that the earth was only thousands of years old, but his observation revolutionized our Western understanding of time. Scientists now believe the true age of the earth to be 4.54 billion years. All because one person looked closely at a rock, noticed the marks made by time, translated their form, and then told a new story.

My experience at Siccar Point continues to resonate with me. It has made me appreciate all the ways Time is made tangible. It’s in the light that takes eight minutes to travel from the sun, whose warmth on my skin reminds me that everything I see in the present moment is technically an image of the past. It’s in the rocks beneath my feet, some of which retain the visible footprints of dinosaurs in a riverbed not far from my home in Texas. And it’s in the leaves that collect in my gutters, which I should clean out more often than I do. I consider myself a conceptual artist, but I don’t think ideas alone are ever enough. I like to give language physical, material forms, because I believe we might be able to understand something more fully if we can experience it physically. I like to think of time as a sculptural medium. Time binds individual moments and actions together to create new forms, in the same way that oil binds particles of pigment together to create paint. Time itself cannot be made, but if time is a medium, what can be made present with it? Can it be stretched and compressed like clay? Can it be turned like wood, carved like stone, bent like glass, or woven like twine? If we use time to make new forms, perhaps those forms can help us tell stories that have previously gone untold. In our daily lives, we tend to think in short terms and see the present moment as narrow and small. But the same laws of nature that formed the ripples in those rocks at Siccar Point millions of years ago are still in operation right now.

And it seems like our collective future might depend on our ability to conceive of “this present moment” as much longer and wider than our narrow field of vision can contain. Perhaps, like Hutton, we just have to look more closely at what we already have the ability to perceive. I wonder, what have we yet to notice? And with time as a medium, I wonder what previously unimaginable futures we can make present.

This Present Moment: Crafting a Better World marks the 50th anniversary of SAAM’s Renwick Gallery by celebrating the dynamic landscape of American craft. The exhibition explores how artists—especially women, people of color, LGBTQ+, and Native artists—have crafted spaces for daydreaming, stories of persistence, models of resilience, and methods of activism that resonate today. In order to craft a better world, it must first be imagined. This story is part of a series that takes a closer look at selected artists and artworks with material drawn from exhibition texts and the catalogue.