Drips of pale brown glaze cascade rhythmically down the sides of a large, bulbous jar by the craftsman David “Dave” Drake (ca. 1800–after 1870) generously donated to SAAM in 2021, by Ann and Tom Cousins.

Drake was an African American potter known for the massive signed stoneware he crafted in nineteenth-century Edgefield, South Carolina. The exceptional scale and heft of Drake’s ceramic jars, and the practice of incising his name and short poems into the sides of them, are distinctive features of his work and make his output unique for the nineteenth-century in the United States’ Deep South.

To be able to form pottery of such magnitude, Drake used a combination of techniques. After turning the bottom portion of his jar on a wheel, he would have added large coils of clay by hand to form the jar’s upper portion. Subtle fissures running horizontally across the jar today reveal the locations where the coils were joined together.

The Edgefield region was a robust, unique site of American pottery, where manufacturing developed in the early nineteenth century. Local clay deposits in the state’s Piedmont region made for a hard, nonporous stoneware, which offered a high quality, low-cost alternative to imported utilitarian ceramics like jars, churns, and pitchers. Lime and wood ash in the “alkaline” glaze produces the light brown or green exterior that became closely associated with ceramics from this area. The Old Edgefield District potteries (which extended across the boundaries of several counties in South Carolina today, including Edgefield) grew strong in part because of natural resources particular to that locale, but also because white manufacturers exploited the unpaid labor of enslaved African men, women, and children originally brought to the area to toil on agricultural plantations.

Drake himself was born into slavery around 1800 and labored in bondage in Edgefield area potteries for most of his life. Although we now know Drake by the surname he adopted after his emancipation, he lived for over six decades as the enslaved often did: without the dignity or humanization of a family name. For this reason, “Dave” is the name we see signed on his jars. Drake was legally freed via the Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863, which freed all those enslaved in Confederate states during the Civil War.

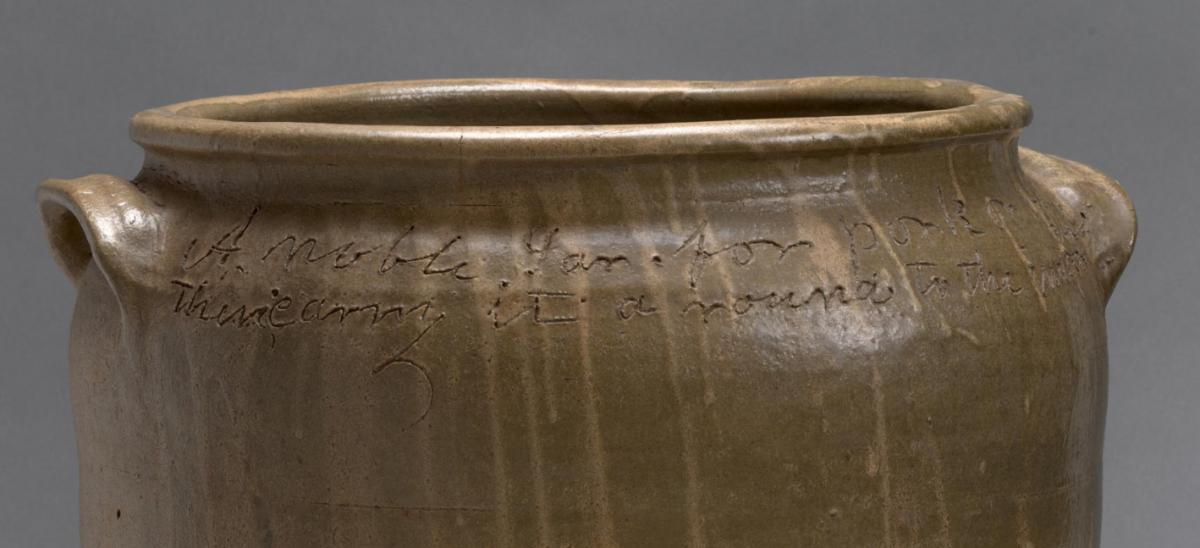

Large vessels like Untitled (Verse Jar) would have likely been used in the store house and kitchen of an area plantation. In this case, Drake inscribed his jar with information about its intended use. While the full meaning of the rhyme’s second line is not known, the first line indicates that this jar was used to preserve and store meats like pork and beef. The meat in this jar may have been salted, smoked, or soaked in brine then sealed with wax or lard for preservation during the winter for use in the summer. A cloth would then have been placed atop the jar and secured with a tie around its curved rim. Additionally, the two parallel hatch marks on the handle of the jar may indicate the capacity of this vessel.

Drake adorned many of his larger storage vessels with short poetic, comical, spiritual, or simply practical inscriptions. His lyricism reflects a unique artistic flourish among Edgefield potters and is a key component of his creative expression.

An 1862 jar by Drake at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History (NMAH) reflects the Christian themes present in some of his poems, reading:

“I made this Jar all of cross,

If you dont repent, you will be, lost”

Another verse on a jar from 1857 in the collection of the Greenville County Museum of Art seems to speak to the poignant separation of families that occurred regularly within the system of slavery:

“I wonder where is all my relation

Friendship to all—and every nation”

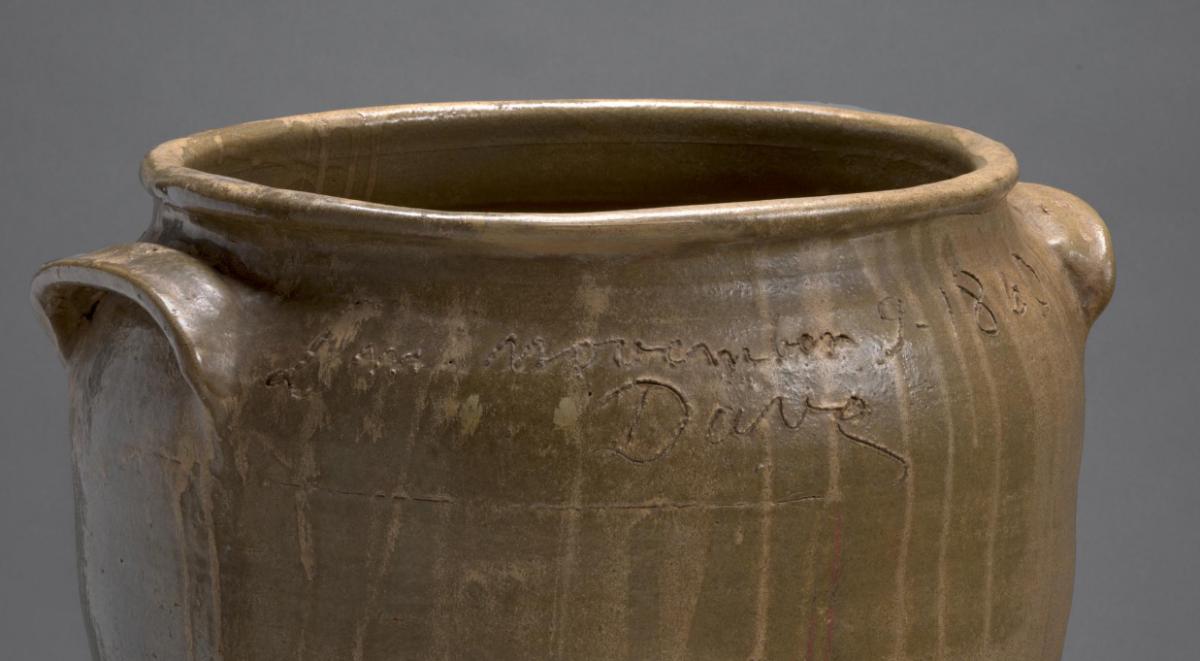

On the other side of the Untitled (Verse Jar), “Dave” prominently identifies himself as its creator—both a rare and transgressive act. Drake is the only Black potter in antebellum Edgefield known to have signed his own work. Even if other enslaved craftsmen who turned, built, glazed, and fired the pottery of Edgefield wanted to sign their work, they would have been unable to do so. In 1834, South Carolina outlawed literacy among its enslaved population as a measure to squash potential organized rebellions. Scholars can only speculate about how David Drake gained his literacy, but he may have learned to read while enslaved by Harvey Drake and working at his partner Abner Landrum’s newspaper, the Edgefield Hive.

Drake’s inscriptions rebuke this racist law and would have openly signaled that resistance to all of the enslaved laborers who encountered his ceramics. His texts have also revealed and acknowledged the work of other ceramicists in Edgefield, like Mark, Abram, and Baddler whose names Drake would sign to jars alongside his own.

More often, pottery in Edgefield bore the stamped mark of an operation’s white owner but not the names of Black artists. Drake hand carved such a mark onto this jar by adding the initials “LM” of his enslaver at the time, Lewis Miles, alongside the date on which the jar was made, November 9, 1860. Carving his own name boldly beneath this line of texts subverts the usually enforced invisibility of enslaved potters.

The alkaline-glazed stoneware made in nineteenth-century Edgefield is a distinctive American ceramic tradition shaped by multiple cultural traditions.

The knowledge of African and African diasporic ceramic practices brought to Edgefield by Black craftspeople actively shaped the objects produced there. Scholars have argued that this influence may be visible in the distinctive small jugs made there that feature decorative faces, which may have continued to facilitate African religious practices in South Carolina.

The recipe for alkaline glazing originated in China, the world’s premier producer of porcelain. The exact way that the method migrated from porcelain manufactories in Jingdezhen to the United States is not known. Additional knowledge of ceramic techniques and object forms came from the European pottery owners who settled in the region.

The relationship of nineteenth-century ceramic manufacturing in Edgefield to the Indigenous inhabitants of the area is unclear, but coiling techniques used in Catawba pottery production (and that of many Native communities) were used in jars like this one.

Want to learn more about David "Dave" Drake, potter and poet? Here's a suggested list for further reading:

- Adrienne Spinozzi, editor. Hear Me Now: The Black Potters of Old Edgefield, South Carolina. New York and New Haven: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, distributed by Yale University Press, 2022.

- Tiffany Momon, Torren Gatson, et al. Black Craftspeople Digital Archive.

- Michael Chaney, editor. Where Is All My Relation? The Poetics of Dave the Potter. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018.

- Cinda K. Baldwin. Great and Noble Jar: Traditional Stoneware of South Carolina. Columbia and Athens: McKissick Museum, University of South Carolina and University of Georgia Press, 1993. Reprinted 2014.

- Leonard Todd. Carolina Clay: The life and legend of the slave potter Dave. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2008.