Last September, an email was forwarded to me with an intriguing subject line: “Photo from Diane Arbus.”

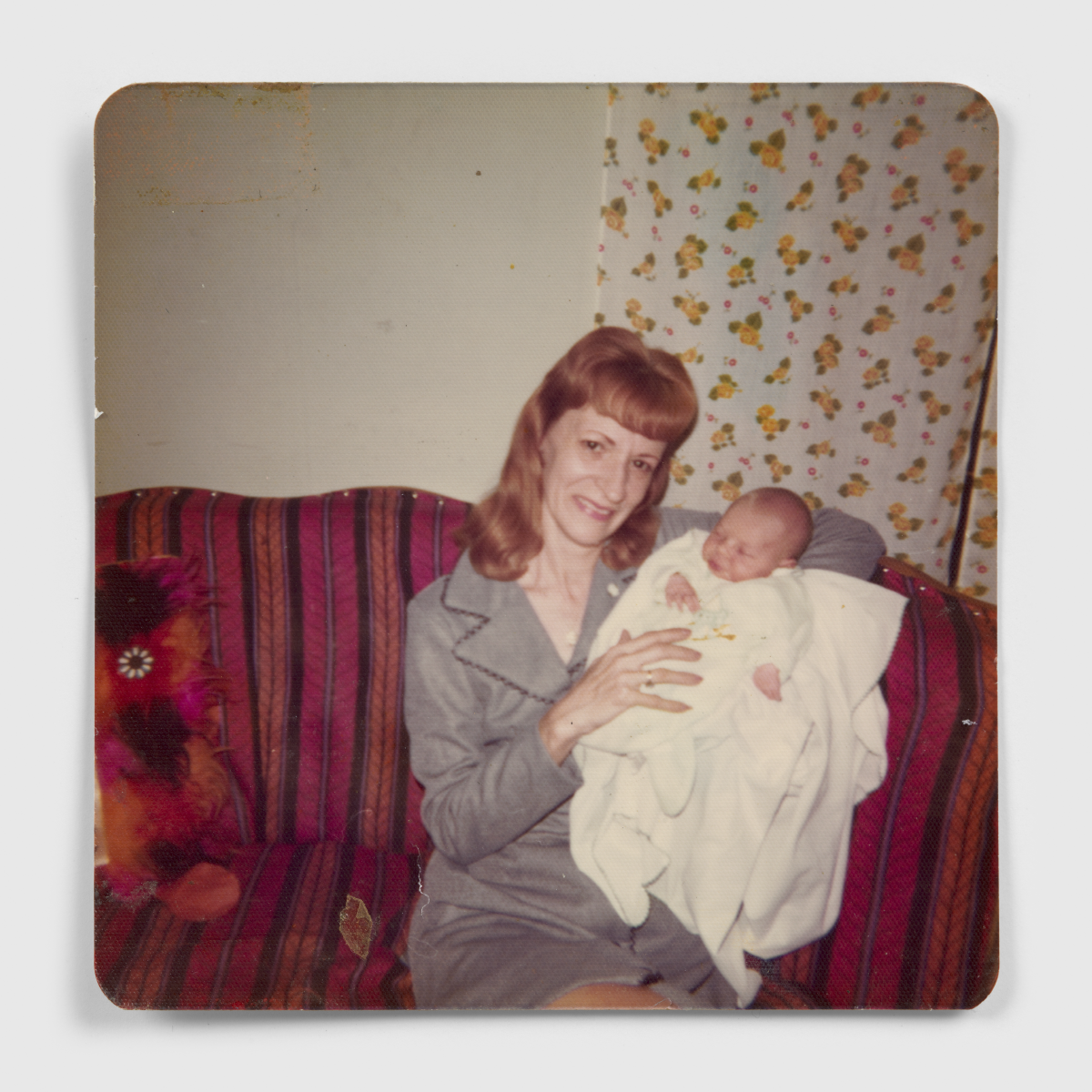

Sender Tina Marie Ulrich-Hodges wrote: “I recently came across a search online with a photo of a lady with a monkey. The photographer was Diane Arbus. The lady holding the monkey was Gladys ‘Mitzi’ Ulrich. She was my grandmother! I’m so blessed to know that her image was seen by so many.” Attached to the email was a snapshot of Gladys Ulrich holding a newborn with Tina Marie’s caption: “Here she is holding me just home from the hospital.” On the verso of the snapshot Gladys Ulrich had written, “This is a picture of Tina. I’m so proud of my granddaughter.”

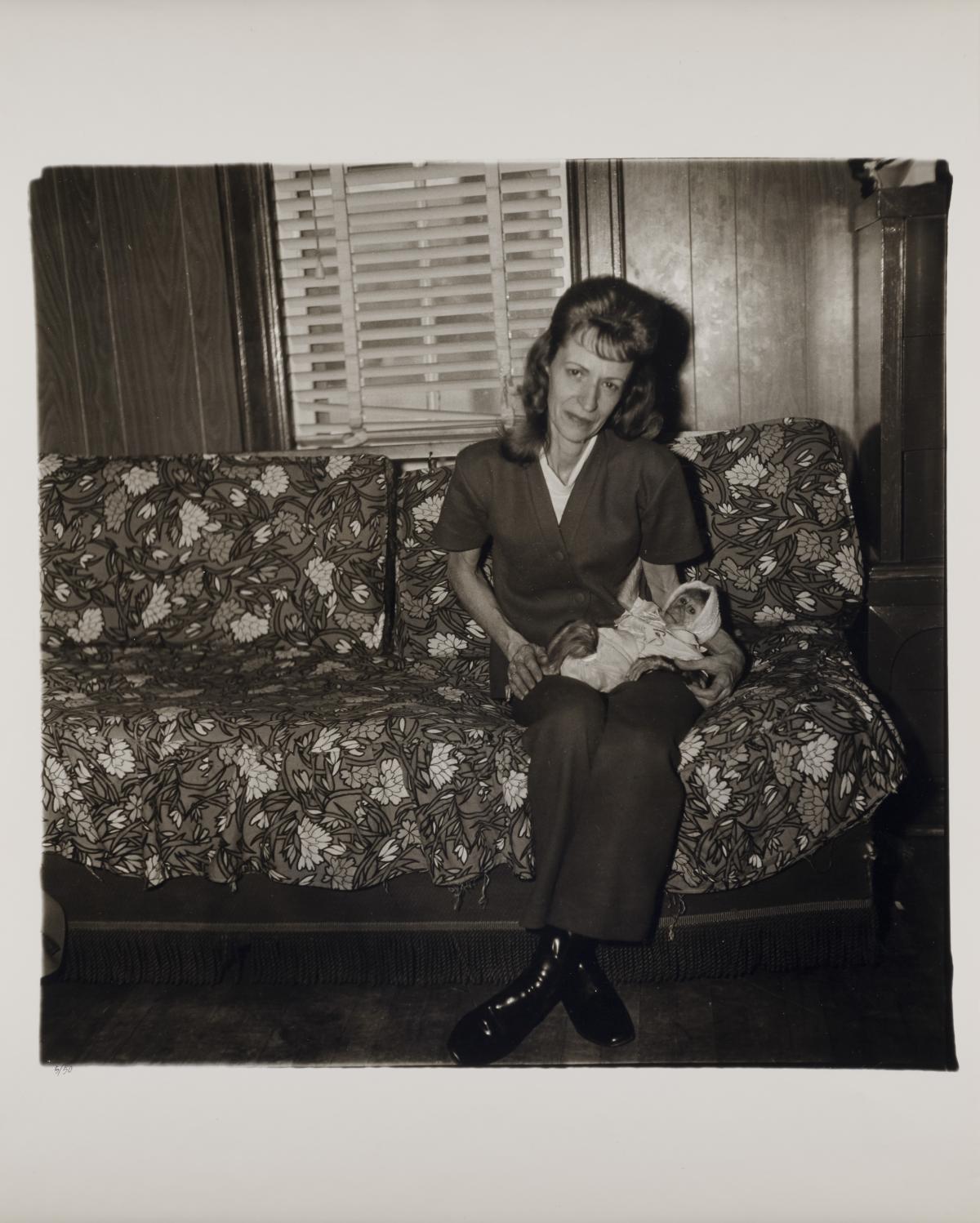

A woman with her baby monkey, 1971, was made for Diane Arbus’s last assignment, for a volume of the popular Time-Life book series Life Library of Photography: The Art of Photography. Drawing mainly from the publisher’s vast picture library, the book also included a special section, “Responding to the Subject: Assignment: Love,” for which photographers including Arbus were commissioned.

According to the editors, skilled practitioners pay attention to their personal responses, what they think or feel about a subject while making a photograph, in order to convey their experience through the image. In the accompanying text to Arbus’s photograph in the book, editors explained she used a flash to simulate the harsh shadows of snapshot photography, “catching a flavor” of total ordinariness. They concluded, quoting Arbus, “And the effect is emphasized by the woman, who ‘seems extremely serious and grave, in the same way you’re grave about the safety of a child.’”

Arbus spoke about A woman with her baby monkey, 1971, to the students in her master class. “Recently I did a picture—I’ve had this experience before—and I made rough prints of a number of them. There was something wrong in all of them. I felt I’d sort of missed it and I figured I’d go back. But there was one that was just totally peculiar. It was a terrible dodo of a picture. It looks to me a little as if the lady’s husband took it. It’s terribly head-on and sort of ugly and there’s something terrific about it. I’ve gotten to like it better and better and now I’m secretly sort of nutty about it.”

Arbus often wrote extended captions that conveyed details beyond the photograph about her encounters with subjects, her thoughts and feelings about those encounters. The caption she submitted with A woman with her baby monkey, 1971, was not published with it: “This is Mrs. Gladys (‘Mitzi’) Ulrich . . . with Sam, the baby, a stump-tailed macaque monkey. . . . The original Sam hung himself by accident. It was hard for her to tell about it. . . . ‘It’s God’s will. If you’re deserving, you’ll find what you’ve lost. I’ve had a wonderful life and a lot of love. I can’t say I’ve missed out on love.’”

Looking at Arbus’s photograph alongside the one sent by her subject’s granddaughter, Arbus’s skill with the snapshot aesthetic is evident. The images are nearly identical. Considered in relation to her late work, A woman with her baby monkey, 1971, was made when she was working on the Untitled series, between 1969 and 1971, photographing at residences for people with developmental disabilities. As her daughter Doon Arbus wrote of that work, “she surrenders precision for lyricism, fixedness for movement, irony for a kind of emotional purity, authority for tenderness.”

A woman with her baby monkey, 1971, is a tender photograph about love. That tenderness is the source of its enduring attraction for me. The editors of The Art of Photography, writing for an audience eager to grasp what goes into the making of a photograph, focused on Arbus’s technique. What draws me to the photograph is not her technique, but her empathy. Its affect, not its effect. What I love about A woman with her baby monkey, 1971, is not the technique of ordinariness, but the metaphor of ordinariness. For Arbus, it was nothing exceptional to love a monkey as one does a child. In making the photograph she surrendered technique for affect, the hallmark of snapshot photography that also characterizes her Untitled photographs. It was this, I think, that Tina Marie Ulrich-Hodges felt when she discovered the photograph, responding to it with the same love and pride for her grandmother that her grandmother had once expressed for her through a photograph.

Thank you for sharing, Tina Marie.