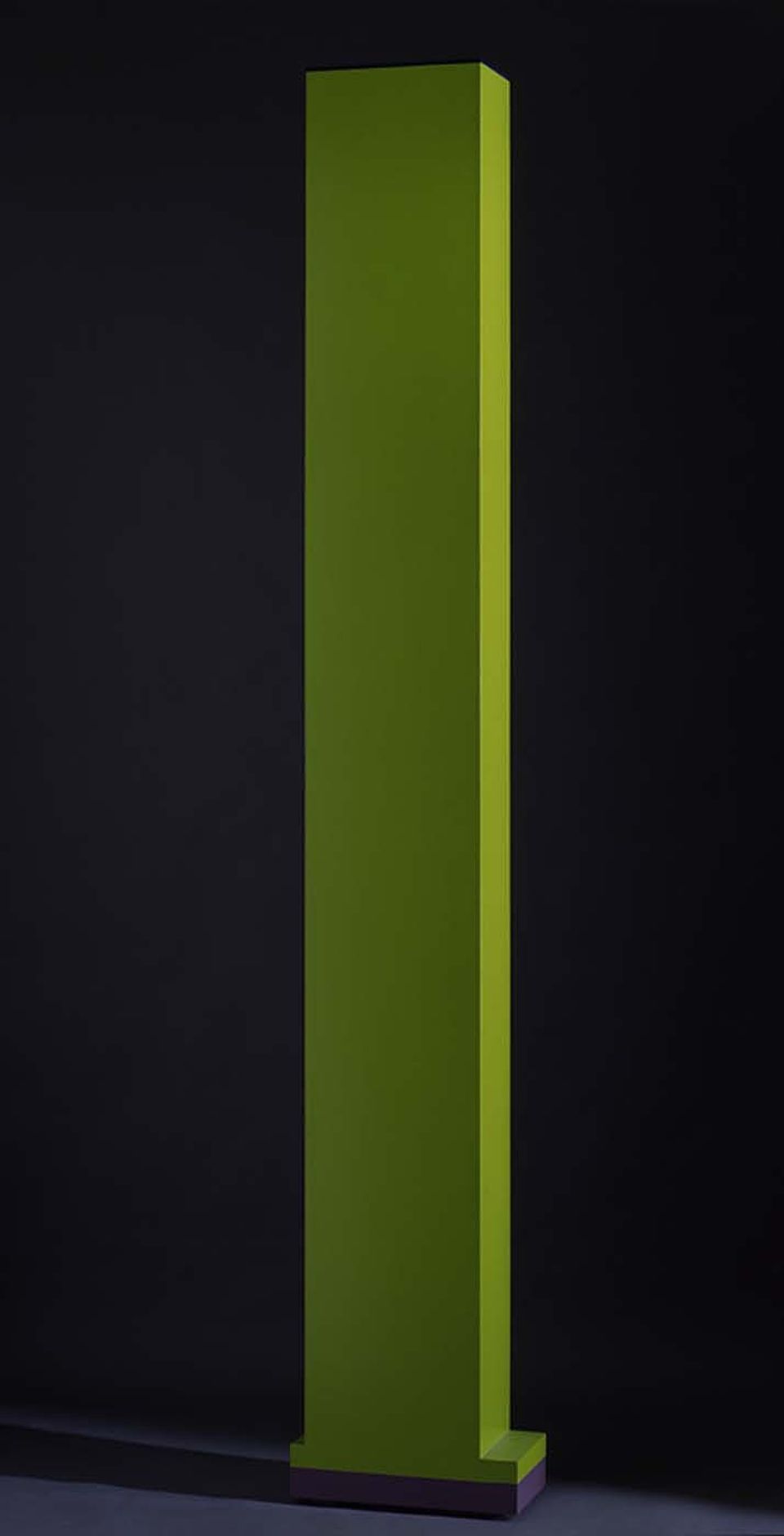

The other day I went searching for a painting on the third floor of the museum—nothing in particular, but something to quench my visual thirst, as it were. I walked into a room with a Helen Frankenthaler and a Morris Louis, and was immediately drawn to the three-dimensional piece that stood out from the other artwork in the room. Ann Truitt’s 17th Summer is a wooden sculpture nearly eight feet tall, painted in the most wonderful shade of green: a green that looks as if all the chlorophyll in every leaf in the world was poured into the vat of its being. Totemic in feeling, the sculpture seems to have a “you are here” quality to it, like an old-fashioned marker on a highway.

I had met Truitt about seven years ago, and had lunch with her at her house in Northwest, Washington, DC. A few years later, I would write a book on John F. Kennedy for young readers, and it turned out that one of Truitt’s children was in the White House nursery with John and Caroline. Truitt told me how all of the mothers took turns helping out, even Jacqueline Kennedy who used to wear a puffy pink sweater because all the children liked to touch it. (So many experiences are saturated in color whether it’s green, pink, blue, or yellow.)

That memory of color and seeing the world as a child came back to me as I stood in front of 17th Summer, thinking how this sculpture was in some way about Truitt’s own daughter Mary, about to embark on adulthood. Green is the color of something new, the color of something about to go out into the world.

Like every interesting work of art you walk right into it, and it somehow manages to walk into you at the same time.

Related Post: Museum Lighting: How We Do It