E. Carmen Ramos became the Smithsonian American Art Museum's curator of Latino art last fall. Now that she's had a chance to get settled, we caught up with her to ask about her interests and the rich holdings of Latino art in the museum's permanent collection.

Eye Level: Can you define Latino art for me? That's probably a tall order!

E. Carmen Ramos: That is a very good, basic question, which ironically is hard to answer. Latino art is an imperfect umbrella category that refers to artworks created by what I like to call American artists of Latin American descent. Artists from diverse generations, backgrounds, and experiences can fall into the category: Puerto Ricans, Mexican-American and Chicanos, Cuban-Americans, Dominican-Americans, and the list goes on. While it would seem that the term encompasses art works by immigrant artists from Latin America, it's a lot more complicated than that. Historically speaking, not all Latino groups have immigrant roots. Many Mexican-American communities trace their origins to the Southwest when this part of the United States was Mexico. Therefore, they did not migrate, but rather became Americans overnight when the border was redrawn as a result of the Mexican American War of 1848. Puerto Ricans are another group who are not immigrants. The island became incorporated into the United States after the so-called Spanish-American War of 1898, and since 1917, Puerto Ricans have been citizens of the United States. And this is the tip of the iceberg; every group encompassed by the category "Latino" has its own nuanced history. And we haven't fully broached the art part of your question.

EL: Tell me something about Latino art in the collection of American Art. What is the time span? What are some of the strengths, and what are some of the gaps that you are hoping to fill?

ECR: The Latino collection is very broad in terms of chronological span and media. It includes important examples of colonial paintings and sculpture from the southwest and Puerto Rico that speak to the Hispanic origins of life on this continent and in the Americas. Actually, the oldest work in all of American Art's collections is a small religious painting, Santa Barbara, done sometime between 1680 and 1690 by an unidentified Puerto Rican artist that came into the museum's collection through Teodoro Vidal. Thanks to a gift from the Chicano scholar Tomás Ybarra-Frausto, we have an excellent collection of Chicano graphics from the 1960s and on. The collection is also strong in work by artists who rose to prominence before and during 1980s and 1990s such as Carlos Almaraz, Frank Romero, Pepón Osorio, Ana Mendieta, Carlos Alfonso, Amalia Mesa-Bains, and Luis Jiménez. As I consider new works for the collection, I'm eager to challenge audience expectations of what is considered Latino art. Along these lines, we recently acquired works by three exciting East Coast-based artists: several film-based works from the late 1950s by Rafael Montañez Ortiz, who was a key member of the international avant-garde movement known as Destructivism, and several paintings by Freddy Rodríguez and Paul Henry Ramirez, two artists from different generations that both engage notions of the body through hard-edged, geometric and abstract imagery. What I'm seeking to do is to capture the diverse vitality of Latino art. The field does not confine itself to any one mode of aesthetic production.

EL: Do you have any personal heroes, people who helped to shape your views on art, or your opinions as a curator?

ECR: Even though I've mostly been affiliated with large, mainstream museums, my curatorial outlook was influenced by the activities of alternative and culturally-specific museums in my hometown of New York City, such as the Studio Museum in Harlem or El Museo del Barrio, which mounted pioneering exhibitions and programs devoted to artists traditionally left out of the canon. There are many individuals who I saw as role models from Kinshasha Holman Conwill, (now Deputy Director of the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture), to Susanna Leval and Luis Cancel. The challenge for scholars of my generation is to develop models that successfully transfer that kind of alternative energy into a different historical moment and context. What kind of work can be done here within the national space that is the Smithsonian? I'm also intrigued by that fact that the Smithsonian's audience is very different than that of a culturally-specific museum. We have a unique opportunity to educate a broad public and expand their understanding of what constitutes American art and culture.

EL: Tell me a little about the exhibition you're putting together at the museum for 2013? Do you have a title for it yet?

ECR: The exhibition will be drawn primarily from our permanent collection and will frame Latino art from a different perspective. I'm fascinated with how the history of Latino art has been largely told in culturally-specific exhibitions, most of which have been presented at culturally-specific institutions. This history—which speaks to how Latino art has been marginalized from the category of American art—has placed Latino art in a kind of bubble, separated from the aesthetic and national context in which it was born. What does it mean to seriously consider Latino art as what it is, American art? How does this work complicate, or shift our understanding of American art and culture? I'm still not set on a title for the exhibition. One rather minimal option is América, or America spelled in Spanish. This title at once affirms the American-ness of Latino art, yet also suggests that Latino art changes what we understand America to be.

EL: In terms of works currently on view at the museum, can you choose a few that would be on your "do not miss" tour?

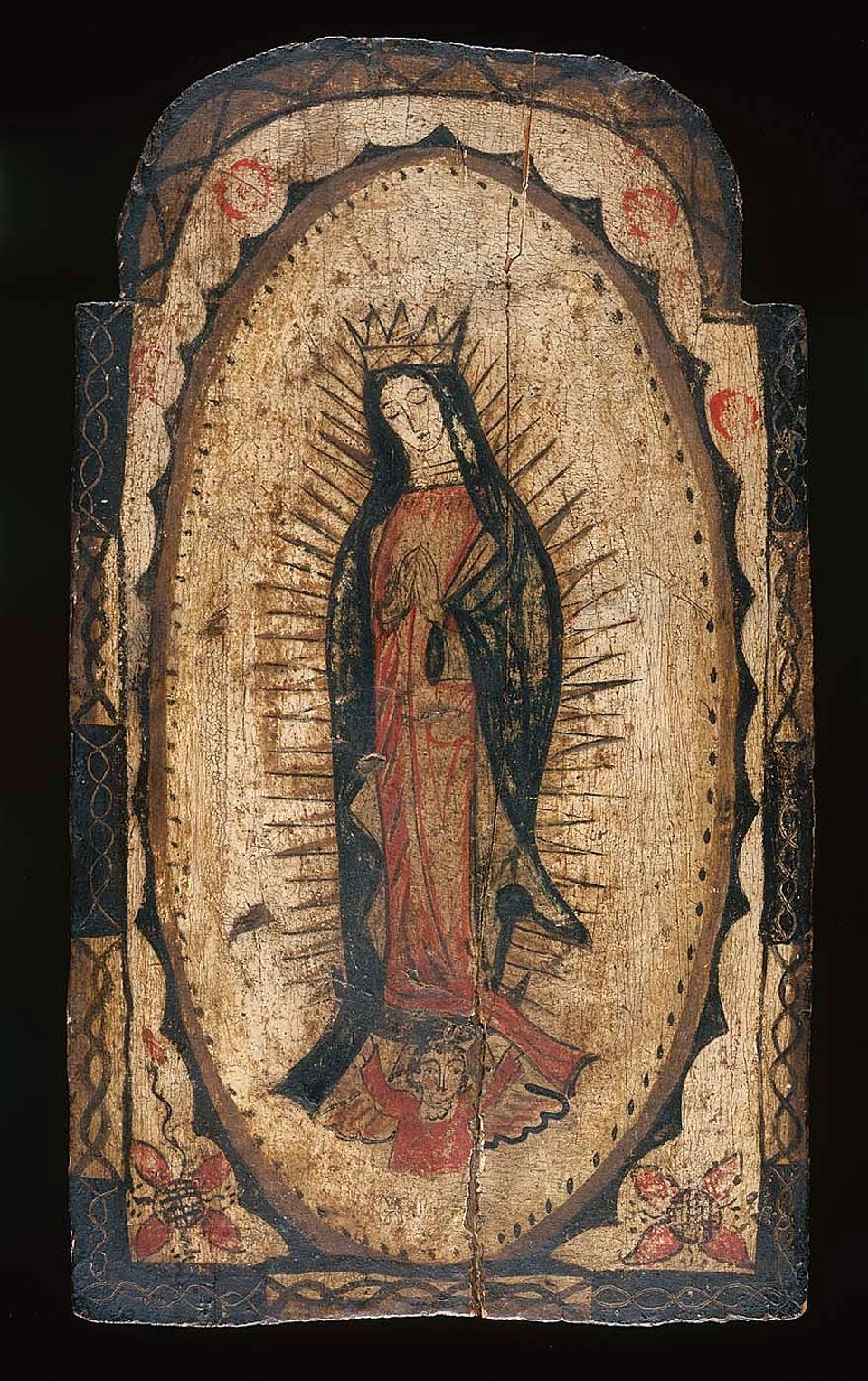

ECR: The humble beauty of Our Lady of Guadalupe, (ca. 1780-1830) by the southwest-based artist Pedro Antonio Fresquís has always made this one of my favorites. Some of my "can't miss" selections are stored away right now, but will be included in the 2013 exhibition. A must see work that falls into that category is Luis Jiménez's Man on Fire, from 1969, which has such a rich history. While works by Latino artists entered the collection as gifts or government transfers from the inception of the museum's history, Man on Fire is probably the first work by a Latino artist that the institution pursued. It was featured in the first Latino exhibition ever presented at American Art, Ancient Roots/New Visions from 1979, which was the first nationally touring exhibition devoted to Latino art. So the work has a kind of "Jackie Robinson" status. Jiménez also deliberately used fiberglass—an industrial and commercial material composed of plastic and glass fibers—to create his sculptures. He was very much a craftsman and wanted to use a material born out of his contemporary times. Thus, the work is both popular in subject and material and resonant with Jiménez bicultural heritage. And there is so much more to say, but people will have to wait until the exhibition opens to hear more.

E. Carmen Ramos asumió el cargo de curadora de arte latino para el Smithsonian American Art Museum el pasado otoño. Ahora que ella ha tenido la oportunidad de ubicarse, la entrevistamos para preguntarle acerca de sus intereses y de la rica representación de arte latino en la colección permanente del museo.

Eye Level: Esta es probablemente una pregunta difícil: ¿Podrías definir el arte latino para mí?

E. Carmen Ramos: Es una pregunta muy básica, pero irónicamente, es difícil de contestar. El arte latino es una categoría imperfecta. Se refiere a obras de arte creadas por lo que me gusta llamar "artistas estadounidenses de origen latinoamericano." Artistas de diversas generaciones, orígines y experiencias pueden caer en esta categoría: puertorriqueños, mexicano-americanos y chicanos, cubano-americanos, dominicano-americanos... y la lista continúa. Si bien parece que el término abarca obras de arte creadas por artistas inmigrantes de América Latina, la realidad es mucho más complicada. Históricamente hablando, no todos los grupos latinos tienen raíces inmigrantes. Muchas comunidades mexicana-americanas tienen sus orígenes en el suroeste, cuando esta parte de los Estados Unidos era México. Por lo tanto, no inmigraron, si no que se convirtieron en estadounidenses de la noche a la mañana cuando los límites de la frontera cambiaron como resultado de la guerra entre México y Estados Unidos de 1848. Los puertorriqueños son otro grupo que no inmigraron. La isla se incorporó a los Estados Unidos después de la llamada Guerra Española-Americana en 1898, y desde 1917, los puertorriqueños han sido ciudadanos de los Estados Unidos. Y esto es apenas la superficie: cada grupo que abarca la categoría de "latino" tiene su propia historia matizada... y todavía no hemos abordado plenamente el tema del arte en su pregunta.

EL: Cuéntame acerca de las obras de arte latino en la colección del American Art Museum. ¿Cuál es el período de tiempo que abarcan? ¿Cuáles son algunos de los aspectos fuertes y cuáles son algunas de las carencias que está esperando resolver?

ECR: La colección latina es muy amplia en términos de período cronológico y medios artisticos. Incluye ejemplos de pinturas coloniales y escultura del suroeste de los Estados Unidos y Puerto Rico que hablan de los orígenes hispanos de la vida en este continente y en las Américas. En realidad, la obra más antigua de todas las colecciones del American Art es una pequeña pintura religiosa, Santa Bárbara, hecha entre 1680 y 1690 por un artista anónimo puertorriqueño que entró en la colección a través de un regalo del coleccionista Teodoro Vidal. Gracias a un regalo del erudito chicano Tomás Ybarra-Frausto, tenemos una excelente colección de gráficos chicanos de la década de los 1960 en adelante. La colección es también muy numerosa en obras de artistas que surgieron antes y durante las décadas de los 1980 y 1990 como Carlos Almaraz, Frank Romero, Pepón Osorio, Ana Mendieta, Alfonso Carlos, Amalia Mesa-Bains, y Luis Jiménez. Mientras considero nuevas adquisiciones para la colección, tengo en mente desafiar las expectativas del público en cuanto a lo que se considera arte latino. En este sentido, recientemente hemos adquirido obras de tres interesantes artistas residentes en la costa este: varias obras basadas en películas de la década de 1950 por Rafael Montañez Ortiz, quien fue un miembro clave del movimiento internacional – vanguardista conocido como destructivismo, y varias pinturas por Freddy Rodríguez y Paul Henry Ramírez, dos artistas de diferentes generaciones, que comparten un interés en la imagen del cuerpo humano a través de un idioma geométrico y abstracto. Mi visión es capturar la vitalidad diversa de arte latino. La definición no se limita a cualquier medio o producción estética.

EL: ¿Tiene usted algún "heroe" personal? Por ejemplo, personas que ayudaron a dar forma a sus puntos de vista sobre el arte o sus opiniones como curadora?

ECR: A pesar de que siempre he estado relacionada con museos de gran escala, mi punto de vista curatorial ha sido influenciado por actividades de museos alternativos y culturalmente específicos en mi ciudad natal, Nueva York. Por ejemplo, el Studio Museum de Harlem o el Museo del Barrio, han instalado exposiciones pioneras y programas dedicados a artistas tradicionalmente excluidos del canon. Hay muchas personas que son para mí modelos a seguir, como Kinshasha Holman Conwill, (en la actualidad directora adjunta del Museo Nacional de Historia y Cultura Afroamericanadel Smithsonian), Susanna Leval y Luis Cancel. Lo dificultoso para eruditos de mi generación es desarrollar modelos útiles que transfieran ese tipo de energía alternativa en un contexto y momento histórico diferente. ¿Qué tipo de trabajo se puede hacer aquí en un espacio de acceso nacional como el Smithsonian? Me intriga el hecho de que la audiencia del Smithsonian es muy diferente a la de un museo culturalmente específico. Tenemos una oportunidad única para educar a un público extenso y ampliar su comprensión de lo que constituye el arte y la cultura de los Estados Unidos.

EL: Cuéntame un poco sobre la exposición que se está preparando para el 2013? ¿Ya tiene un título?

ECR: La exposición estará compuesta principalmente por obras de nuestra colección permanente, y examinará el arte latino desde una perspectiva diferente. Me fascina la forma en que la historia del arte latino ha sido en gran parte contada en exposiciones culturalmente específicas, la mayoría de los cuales se han presentado también en instituciones culturales específicas. Esta historia, que habla de cómo el arte latino ha sido marginado de la categoría de arte americano, ha separado el arte latino del contexto estético y nacional en el que nació. ¿Qué significa considerar seriamente el arte latino como lo que es, arte estadounidense? ¿Cómo es que el arte latino cambia o complica nuestra comprensión del arte y la cultura de este país? Todavía no he decidido un título para la exposición. Una opción minimalista es "América", o America escrito en español. Este título a la vez afirma la "Americanidad" del arte latino, pero también sugiere que el arte latino cambia nuestro concepto de lo que consideramos los Estados Unidos.

EL: En cuanto a las obras que están al la vista en el museo, podrías recomendar obras que "hay que ver"?

ECR: La belleza humilde de Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe, (hecha alrededor de 1780-1830) por el artista radicado en el Suroeste, Pedro Antonio Fresquís, siempre ha sido una de mis favoritas. Algunas de mis selecciones de obras que "hay que ver" están por ahora en nuestro almacén, pero muchas de ellas se incluirán en la exposición de 2013. Una obra que cae en esa categoría es Man on Fire (Hombre en llamas) de Luis Jiménez, realizada en 1969 y que tiene una rica historia. Mientras que muchas obras de artistas latinos entraron en la colección como regalos o transferencias del gobierno desde el inicio de la historia del museo, Man on Fire es probablemente la primera obra de un artista latino que la institución buscó adquirir. Fue una de las piezas principales en la primera exposición de arte latino presentada en el American Art Museum, Ancient Roots/New Visions (Raíces Antiguas /Nuevas Visiones) en 1979. Esta fue la primera exposición nacional dedicada al arte latino que salió de gira. Así que esta obra tiene el estatus de carácter de "Jackie Robinson". Jiménez utilizo deliberadamente la fibra de vidrio, un material industrial y comercial compuesto de fibras de plástico y de vidrio para crear sus esculturas. El era un maestro muy hábil y quería usar un material nacido de su época contemporánea. Así, la obra es a la vez popular en tema y materiales y resuena con el patrimonio bicultural de Jiménez. Y hay mucho más por decir, pero el público tendrá que esperar hasta que la exposición se abra para saber más.