Curator of Time-Based Media Saisha Grayson's 2018 blog post on World AIDS Day seems especially poignant as we grapple with our current pandemic(s) and the collective actions needed to address them. In the early years, A Day Without Art encouraged museums to close their doors or shroud their masterpieces to prompt shared reflection on those lost to AIDS. Perhaps this year’s longer closures can be reimagined as not only health precautions, but as extended opportunities to acknowledge the continual, disproportionate losses and suffering that both AIDS and Covid-19 have brought to communities across the United States, and around the world.

December 1, 1988, thirty years ago today, was designated by the World Health Organization as the first World AIDS Day, in order to raise awareness of the growing global pandemic. In 1989, Visual AIDS organized the first Day Without Art, encouraging cultural institutions across the country to recognize the distinct toll this public health crisis was having on the arts and creative communities. Since then, museums have taken this day to explore different ways to mourn and honor those lost, and to activate and educate audiences around the continuing impact and search for a cure.

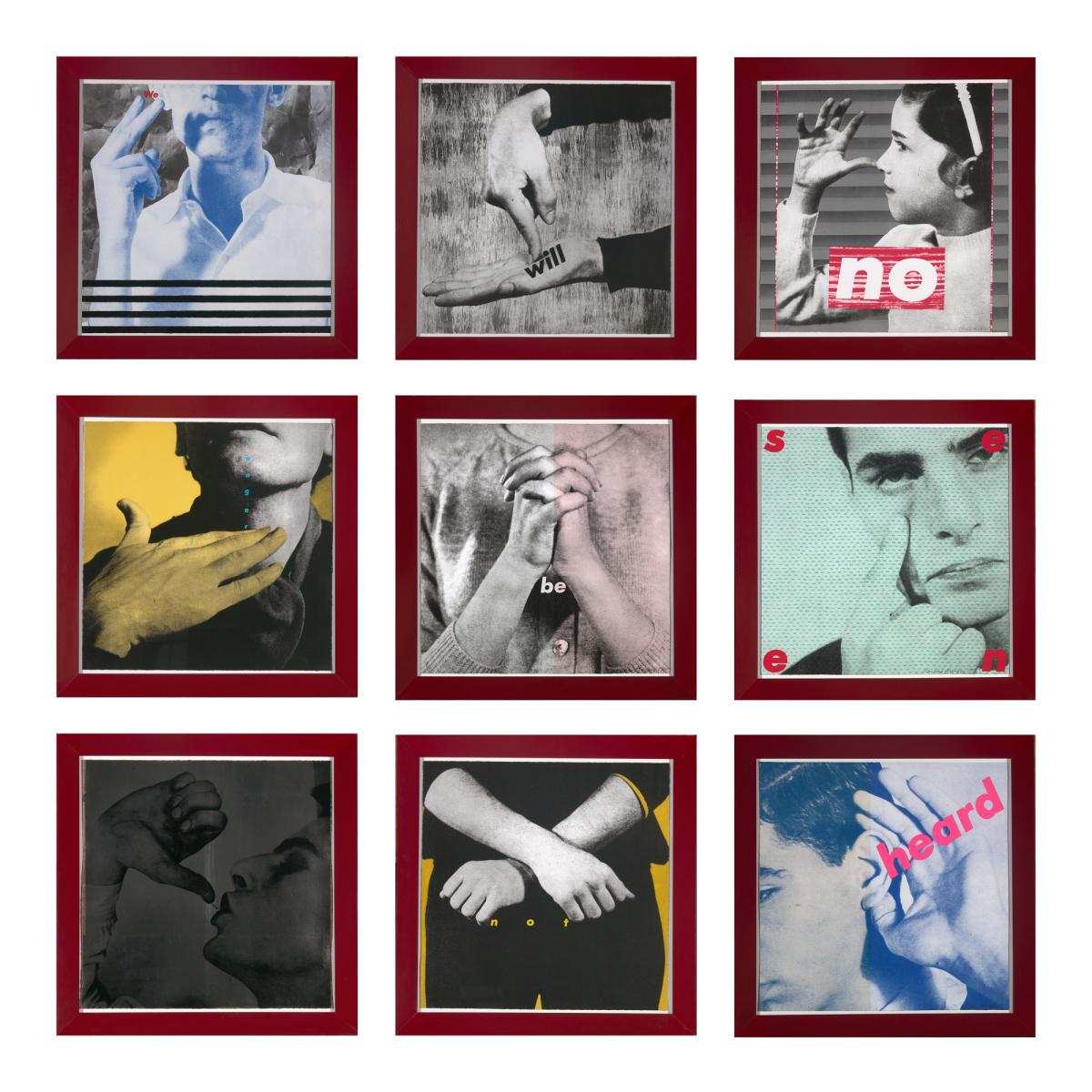

Thinking about what works from SAAM’s permanent collection might speak to this moment of reflection, I pulled up our monumental, multi-part piece by Barbara Kruger, Untitled (We Will No Longer Be Seen and Not Heard). The piece is not obviously connected to AIDS activism, and yet it was made in a key year for the struggle. From the virus's identification in 1981, when 234 deaths were determined to be HIV-related, to 1985, when that number reached 5,636, hard-hit communities in California and New York fought to be heard by public officials as infection rates grew. In 1985, the issue finally broke into national news, with the death of film star Rock Hudson and President Ronald Reagan’s first public address of the topic.

By 1985, Kruger was well known for her dramatic juxtapositions of found photographs and provocative text, which she used to interrogate mass-media images and the messages they encode, particularly from a feminist perspective. However, while the “we” in many of her images is assumed to refer to women, because this particular piece incorporates a range of figures its meaning seems less specific, more open to encompassing all those who have been told to be silent… even when silence might be a death sentence.

Perhaps I thought of this work, then, because it prefigures what would go on to be the animating slogan of AIDS activism in the years that follow. In 1987, a group that came to be known as the Silence=Death Project, created an iconic graphic with that slogan and pink triangle, which became the central image in ACT-UP’s activist campaign against the AIDS epidemic. (A neon incarnation was recently on view in the lobby of the Hirshhorn Museum).

Or perhaps it was because, while I’m still researching to see if there is any way it could be, the figure holding WE like a cigarette reminds me of the late great David Wojnarowicz—painter, photographer, performance artist and AIDS activist—and the subject of a recent major retrospective at the Whitney. He died of the disease in 1992 at the age of 38, and his loss remains all of our loss, never to be forgotten.