Bill Traylor, regarded today as one of America’s most important artists, was born into an enslaved family in rural Alabama around 1853. Traylor and his family continued to work as farm laborers after Emancipation, work that Traylor himself spent some seven decades doing. In the late 1920s, Traylor moved by himself to Montgomery, Alabama. About a decade later, no longer able to take on heavy physical labor, he began to make drawings. What does it mean for Traylor, untrained as an artist, to now be held in such high esteem?

Certainly, part of what makes Traylor’s story so profound is that he chose to become an artist of his own volition; no one suggested he make drawings or showed him how to do it. In fact, in the days of slavery, literacy was strictly the privilege of whites. Reading and writing were regarded as tools of empowerment, and blacks seeking these tools were often harshly punished. Traylor never became literate, and in his time and place, the very act of taking up pencil and paper might have been viewed as an affront to white society—even if it was becoming increasingly common for African Americans to be both educated and successful.

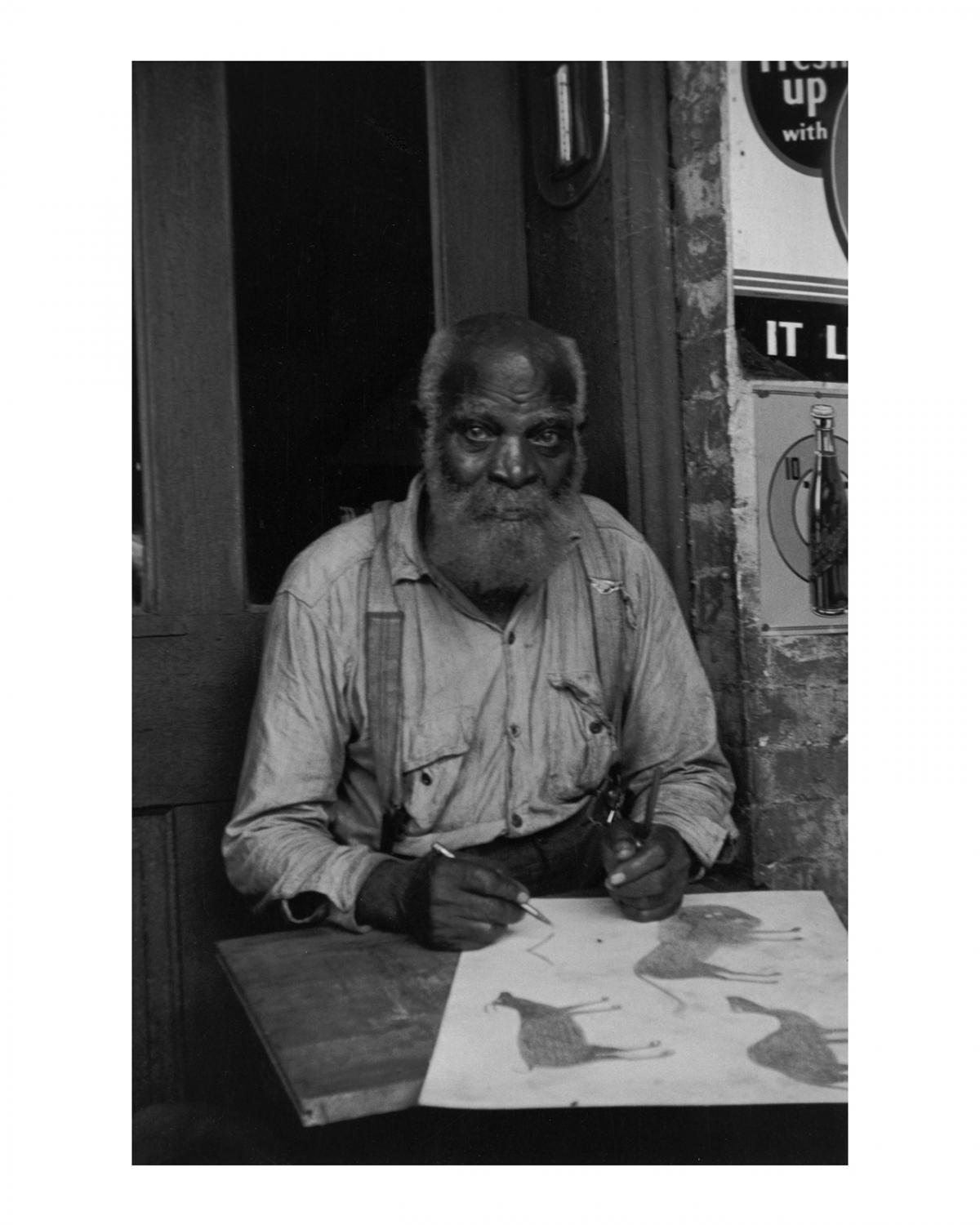

So what Traylor did was radical in multiple ways. He was among the first generation of black people to become American citizens, and Traylor grappled with the meaning of that identity as he sat in the black business district of Montgomery in the 1930s and 1940s and watched a rising class of business owners and community leaders—finely dressed, educated black folks who were strong, creative, and were assertively shaping a cultural identity distinct from that of white America. Traylor created a record not just of his own selfhood, but also of the oral and vernacular culture that had shaped him.

Many terms are bandied about for untrained artists; we often hear them called self-taught, folk, visionary, or “outsider.” Traylor may not have conceptualized being an artist in a predetermined or conventional way, but the way we talk about him and his art matters. Traylor lived and worked quite literally in a different world than that of the mainstream fine arts.. And as is true with any artist, the facts of his life provide meaningful contexts and deeply inform the work he made. It is highly significant that Traylor came through slavery and lived the rest of his days in the Jim Crow South—this life powerfully undergirds the entire body of work.

Still, when we speak of an artist as being successful or important only within a subcategory of art, we diminish an artist’s larger validity. To say, for example, that Traylor is among America’s “most important self-taught artists” is to qualify his importance, to send a signal that his work is ultimately lesser than that of trained, mainstream artists—that it exists in a subcategory without full rank. To call an artist an “outsider” is to note difference as the foremost framework. The term describes the artist, not the art, and ultimately functions as a euphemism for race, class, or social agency. Marketers often grab encompassing terms because they are easy, but “outsider” has always been a disparaging way of grouping individuals by difference, rather than seeking to foster a broader understanding of art and its diverse makers.

Understanding context in a deep way brings meaning to art that is unique and unaffiliated with the mainstream art world, yet it is key to remember that qualifiers always signal disparity. We recognize that it is demeaning and inappropriate to say, for example, that someone is “among the best female employees,” or “among the best black experts,” but we have yet to fully extend this to artists like Traylor. It has been clear for decades that Traylor is among the most important self-taught artists; his work fetches blue-chip prices and is recognized and collected the world over. Today we need to look at the magnitude of what he did against the larger backdrop of art in his nation. He is one of America’s most important artists—no qualifier welcome. Between Worlds fleshes this out and proposes a different, more encompassing course that moves beyond an exclusionary past.

This article originally appeared on the blog of the Princeton University Press.

The exhibition Between Worlds: The Art of Bill Traylor remains on view through March 17, 2019.

# # #

On Tuesday, November 6, from 6-7 pm join SAAM curator Leslie Umberger and folklorist Diana N’Diaye as they discuss the significance that clothing and personal adornment play in Traylor’s work and in African American history and culture. N’Diaye is a curator at the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage.