Karen Canova is a dedicated Luce Foundation Center volunteer and art history enthusiast

The Luce Foundation Center currently has 22 paintings on view by William H. Johnson (1901-1970), one of America’s foremost African American artists and a major figure in 20th century art. Luce visitors may notice that Johnson’s paintings appear to be done in two very different styles. These two styles can be separated into time periods, 1926-1938 and 1939-1945.

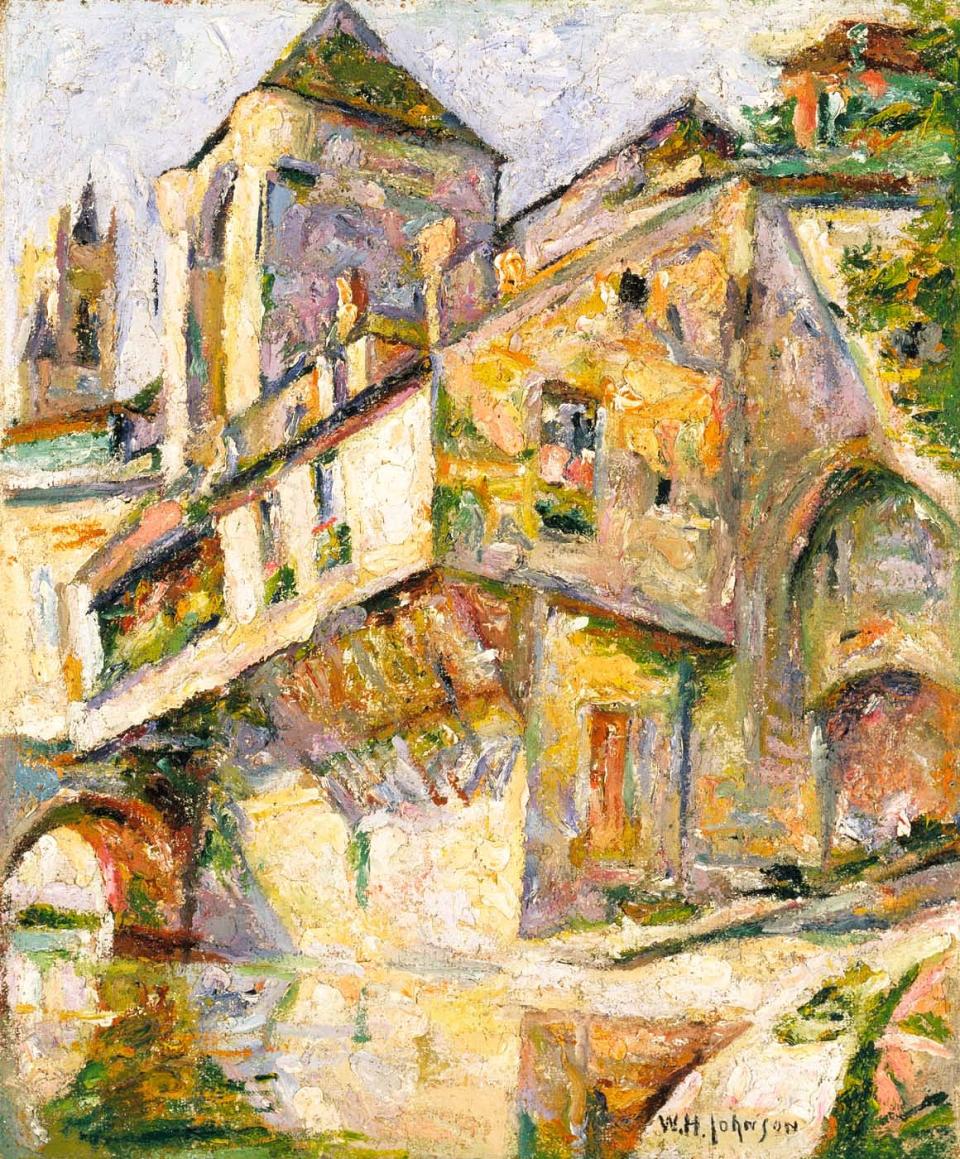

Johnson spent the early part of his career in Europe, primarily due to the lack of opportunity for black artists in the U.S. After studying at the National Academy of Design in New York City, Johnson moved to France in 1926 to continue his studies. While living first in Paris, then in the south of France, Johnson painted in the style of the French Impressionists. The painting Vieille Maison at Porte (ca. 1927), is a good example of the artist’s early style, in which he used thick strokes of color to convey the bright sunlight and reflected shadows that fall on an ancient house in the town of Chartres. At some point while still living in France, Johnson was influenced by the German expressionist painters of the 1920s and changed his painting style to emphasize emotional expression rather than external appearances.*

After three years in France, Johnson returned to the U.S. in late 1929. While planning his return to Europe, he first visited his family in Florence, South Carolina, whom he hadn’t seen in twelve years. In Jim (case 30B), a portrait of Johnson’s sixteen-year-old brother, the background is almost equally divided between dark and light shades, seen as an attempt by the artist to evoke his place between two different worlds.

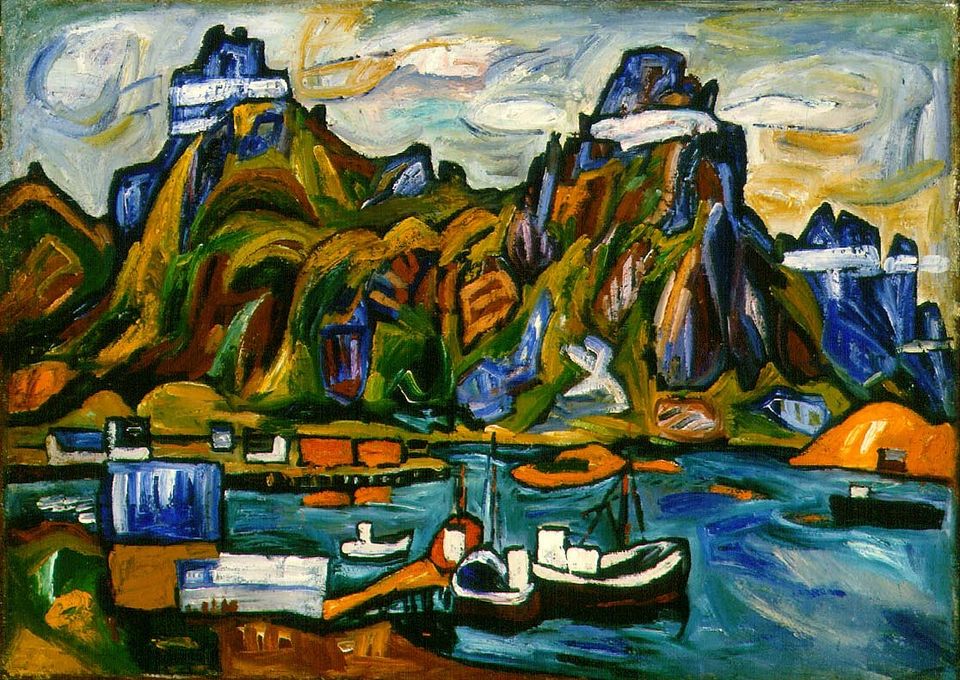

The remaining paintings from Johnson’s European period that can be seen in the Luce Center were all completed when he lived in Scandinavia in the 1930s. Examples include Harbor, Svolvaer, Lofoten (case 30B) and Portrait of a Man (case 30B). While this portrait is almost a caricature, Johnson never intended to satirize his subjects, he always aimed to capture what he called “the essential characteristics” of his sitters, people whose features were shaped by the harsh environments in which they struggled to survive.

In the late 1930s, with Nazism on the rise in Europe and modernist artists increasingly under attack for producing what the authorities labeled “degenerate art,” Johnson and his Danish wife, artist Holcha Krake, moved to New York City. Johnson found work there as a teacher at the Harlem Community Art Center, a Federal Art Project supported by the Works Progress Administration (WPA). Through the Center, Johnson immersed himself in African American culture and traditions, producing paintings characterized by their folk art simplicity and a self-consciously primitive style. Johnson became determined to “paint his own people” and celebrated African American imagery and culture in both rural and urban settings.**

Examples in the Luce Center from this period of his life include The Breakdown (case 31A), Chain Gang (case 31A), and Art Class (case 31B). The Breakdown shows a scene familiar to Americans after years of drought and economic depression, but the title also refers to the moments of despair that punctuate African American blues music. With Chain Gang, Johnson may have chosen this subject while working for the Works Progress Administration, where archivists helped preserve the stories and songs of prisoners. The painting Art Class reflects Johnson’s experience teaching in the Harlem Community Art Center, which gave young African American artists far greater opportunities than Johnson had known two decades earlier.

After the U.S. entered World War II, Johnson painted a large number of works that featured African Americans involved in the war effort, primarily soldiers and nurses. Soldiers Training (case 32A) contrasts the patriotism of black enlistees with the military’s segregationist policies at the time. Black soldiers served in their own units, “black” blood was kept separate from “white,” and recruits took on the most menial jobs at military bases and on ships.

In 2012, the United States Postal Service issued a commemorative Forever stamp honoring Johnson’s work and legacy. The stamp highlights his painting, Flowers (case 36B), a still life depicting a vase of brightly colored blooms on a small table. The Luce Foundation Center is honored to have this painting on permanent display. In addition to the 21 paintings by Johnson on view in the Luce Center, SAAM currently displays five Johnson paintings in various galleries. The Museum owns over 1,000 works of art by William H. Johnson in a variety of media.

References:

(quote) William H. Johnson, An American Modern, edited by Teresa G. Gionis, University of Washington Press, 2011

*William H. Johnson, the Scandinavian Years (Exhibit Catalog), Smithsonian, 1982

**Richard J. Powell, Homecoming: The Art and Life of William H. Johnson, Rizzoli, 1991.