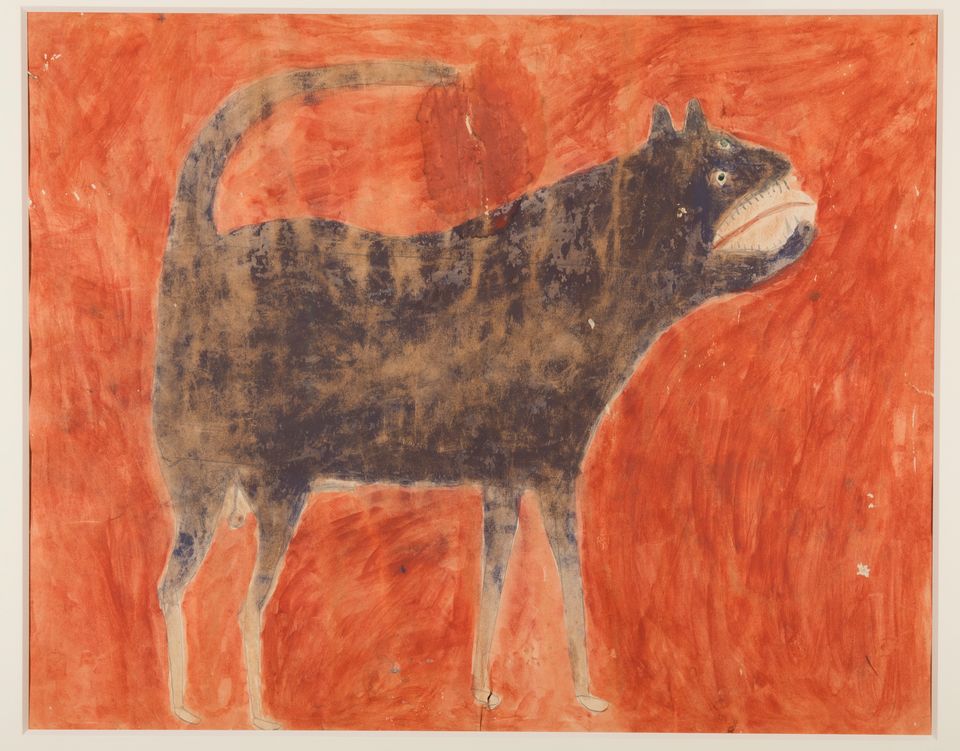

Bill Traylor, Mean Dog (Verso: Man Leading Mule), ca. 1939–1942, poster paint and pencil on cardboard. Collection of Jerry and Susan Lauren © 1994, Bill Traylor Family Trust. Photo: Matt Flynn © Smithsonian Institution

Who was Bill Traylor?

Bill Traylor was born into an enslaved family in rural Alabama around 1853. Although slavery ended when Traylor was about twelve, things in Alabama didn’t change dramatically or rapidly after that, and families like Traylor’s had limited options for finding work, shelter, and safety elsewhere—so they often stayed on as laborers, living in the same cabins as they had before Emancipation. This is what Traylor’s family did.

Traylor spent over seven decades working as a farm laborer. His life was split almost evenly between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, so he was eyewitness to enormous change over a lifetime that almost reached ten decades. Around 1927—Traylor’s wife had died and most of his grown children had given up on life in the South—he made the choice to move, alone, into Montgomery. The city was segregated, and he was increasingly old and frail between then and his death in 1949. But in the last years of his life, Traylor began to draw and paint memories, stories, and dreams recalling that remarkable lifetime and observing black life in an urban setting. Against the odds, many of the artworks he made in the late 1930s and early 1940s survived, and today he is acclaimed as one of America’s most significant artists.

The exhibition and catalogue are titled Between Worlds: The Art of Bill Traylor. What “worlds” was Traylor between?

Traylor’s lifetime spanned an epic period of American history that encompasses slavery, Emancipation, Reconstruction, Jim Crow segregation, the Great Migration, two world wars, and, through it all, the steady rise of African American culture in the South. Traylor didn’t live to see the civil rights movement, be he was among those who laid its foundation. Six years after Traylor died, Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a bus to a white passenger just a few blocks from where Traylor had sat and painted.

Throughout his life, Traylor straddled markedly different worlds: slavery and freedom, plantation and city life, and overarching it all, black and white cultures. “Racial etiquette” was the custom in the Jim Crow South wherein black people had strict and demeaning rules governing what they said and how they behaved in the presence of white people—any minor infraction of which might literally imperil that individual’s life. Traylor knew these systems, and his drawings nimbly employ symbolism, allegory, and ambiguity to send different messages to black and white viewers—to “code switch” as we would say today. He lived between worlds, looking back at a long life of labor and oppression, and ahead at the long, hard road toward freedom his children were traveling on.

What kind of topics did Traylor depict in his artworks?

Traylor covered a lot of territory in his subject matter. He became known not only for deceptively simple renderings of horses, mules, and other animals he knew from farm life, but also for many other species, including dogs, snakes, and birds. Traylor knew these animals and their visages well, but his representations of them are complex, for he also had a deep grasp of their symbolism. For example, the mule as a metaphor for black slaves or laborers, or the snake as a symbol of deceit—the lurking enemy.

Throughout his oeuvre there is a strong thread of storytelling. He often revisits particular themes or memories, and very often the works cohere when seen together in ways they don’t when viewed alone. A particular focus of both the exhibition and the book is to give certain images adjacency and draw out related themes, so that the artworks can function collectively and tell their stories more completely. Traylor depicted people he recalled from plantation days as well as the finely dressed black citizens of Montgomery he saw before him. His drawings are often quite enigmatic, as the artist engaged dreams, superstitions, and various spiritual belief systems.

Some of Traylor’s most iconic drawings present multifaceted narratives, chaotic action that swirls around a house, a tree, or a local site such as the fountain in Montgomery’s Court Square. He devised a manner of presenting story lines, sometimes left to right on the page but more often from top to bottom—or bottom to top. He discovered that vertical arrangements gave the story a different reading: events unfold rapidly or simultaneously, instead of sequentially. The viewer’s eye is caught in a swirling eddy of action that obscures Traylor’s meaning, which, in turn, gave him a higher degree of safety among white viewers. These works have a quality of operatic drama and demand a deep look: narratives that might at first seem humorous are often quite dark; the unspeakable violence of Traylor’s life and times looms large.

Traylor’s body of work is a sizable pictorial record of the oral culture that had shaped him. He embarked on making a record of selfhood that he devised for himself, one picture at a time.

The exhibition, Between Worlds: The Art of Bill Traylor, remains on view at SAAM through March 17, 2019.

This interview originally appeared on the blog of Princeton University Press, publisher of the exhibition catalogue.