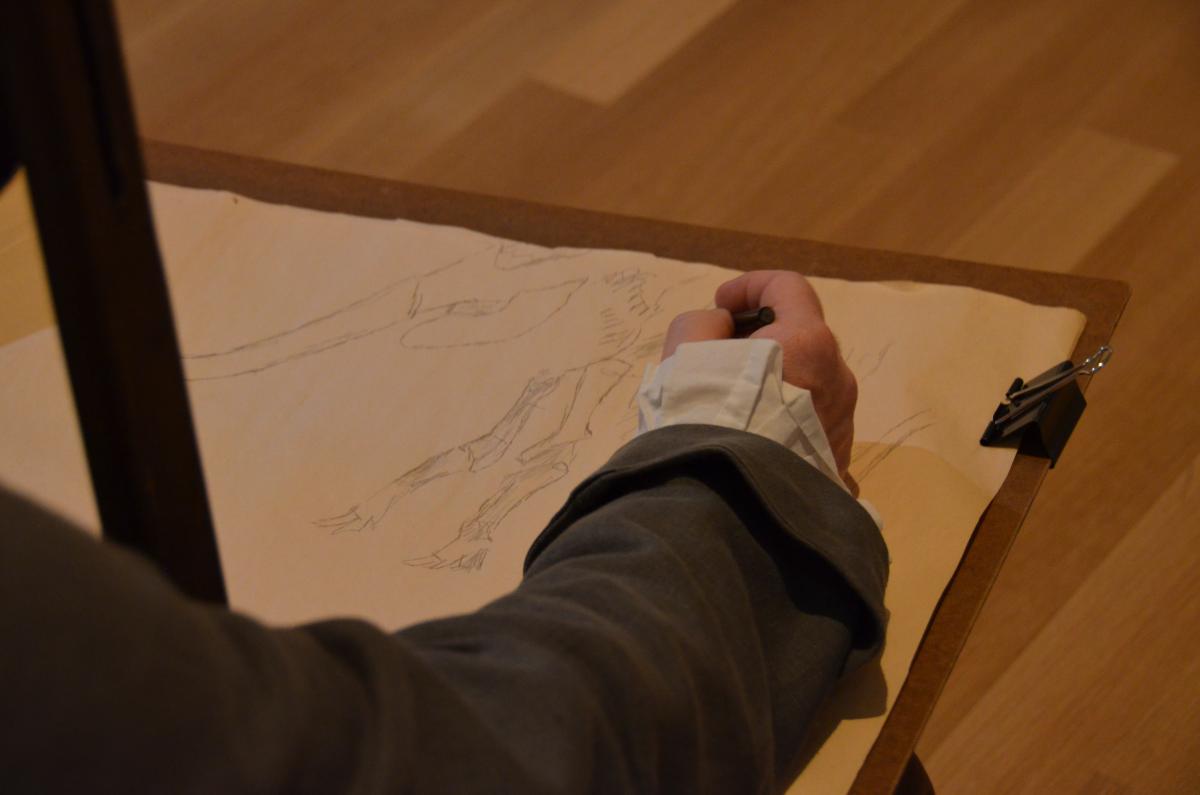

Meet Dean Howarth, a local high school science teacher and an interpreter on the history of science. He has presented "living history narratives" based on the science of Charles Willson Peale and Alexander von Humboldt at Smithsonian Libraries, the National Museum of American History, and other regional museums. Howarth visited SAAM in nineteenth century dress during the summer to sketch the mastodon skeleton featured in the exhibition, Alexander von Humboldt in the United States: Art, Nature, and Culture. He used a "camera lucida," a small sketching tool used in the 1800s similar to a camera obscura but simpler and quicker to use—a favorite tool of 19th-century naturalists, like Humboldt. Enjoy the world of science, discovery, and Alexander von Humboldt through Howarth’s lens.

What were your thoughts on the exhibition? Any particular discoveries or highlights when you came to the museum to sketch the mastodon?

I love the "connectivity" of the exhibition. It wasn't just about items related to or created by Humboldt. It was focused on how the spirit of Humboldt and the developing science of ecology resonated through art, politics, sociology, and literature. In the history of science, there are watershed moments that resemble tributaries and branch out far and wide. Humboldt embodied that, and his influence resonates today.

You call yourself "a curious amateur scientist." As a teacher, what roles do curiosity and discovery play in teaching science? And how do you hope to instill scientific curiosity in your students?

Science can be esoteric and intimidating, especially the way we often present and perceive it today, but it needn't be that way. Einstein said that school often hindered his imagination. He attributed his success to his lifelong curiosity. We need to realize that the youthful curiosity, doubt, and rebelliousness that are already in kids is something that needs to be nurtured and not sucked out of them. I try to remember what it is like to be a kid and hopefully, in turn, preserve the innate wonder found in young people. They are the ones that are going to preserve and explore the wonders of the planet that first inspired Alexander von Humboldt.

What does the camera lucida capture, and how does it work? How is it different from the camera obscura? Who would've used these in Peale's day, and how?

The camera obscura predates the camera lucida by hundreds of years. It was used in the Renaissance by the likes of Da Vinci, who was interested in scientific instruments. At the time, the camera obscura was neither cheap nor an easy way to do art. The idea was you could use lenses to capture an image, and light coming through a pinhole could project the image on a wall. The term "camera obscura” means "darkroom" or "dark chamber." This early model is similar to what you use when looking at an with a pinhole camera.

Once the science of optics took off, scientists realized that they could manipulate and use mirrors to turn the camera obscura into the camera lucida. This device has a lens in the front and a viewfinder in the back, similar to any camera. A projection would be made on a piece of glass that you could look at and be entertained by it, but you could also put a piece of thin paper below the glass and create a very quick sketch of whatever you were looking at. Initially, these were used scientifically, more so than they were used artistically to do scientific sketches in manuals or medical texts. However, soon artists realized it could also be used for art, just like a camera can be used in the world of art or science. And just as I surmise that when the first camera was made, artists were aghast that “Oh somehow we’re cheating.” Da Vinci thought that using the camera obscura was cheating as well. But all in the spirit of science.

How can sketching this ancient mastodon using a historical, scientific instrument illuminate aspects that are not visible to the naked eye?

Although my naked eyes do work passively well with the refractive assistance of my spectacles, the issue is not so much that it’s the naked eye, but it’s the untrained artist’s hand. Thanks to devices like the camera lucida, if I was going into the field, let's say to sketch a living creature, like a bison or bird, or a landscape, I would be able to do it without years of learning how to sketch. If I were to bring an artist with me on an expedition, that’s another entire person with a specialized skill that would have to be trained and outfitted for the journey. But with a camera lucida handy, you could have an assistant who is helpful in the field and a decent drafter use this device to bridge the gap between real artistic skill enough to get the point across. This allows for anyone to make lasting records of their observations. In fact, camera lucidas were marketed for amateurs to be able to do what otherwise an artist would only be able to do. So, thanks to this device, rather than sitting down with oils and paint, I can get a quick enough sketch of this mastodon.

As a life-long fan, what drew you to Humboldt, and what lessons can his work teach to students today?

This is a perfect question because what drew me to being a science educator goes all the way back to 1979–1980. This was when one of my personal heroes, Carl Sagan, put out his series, Cosmos. Inspired by Humboldt, his notion of how all sciences interconnect into the human experience and how the power of our intellect allows for some level of understanding to the chaos that is the opposite of Cosmos is fascinating. Carl Sagan popularized science by being highly visible: he was on TV, in newspapers, in books. Even as an accomplished scientist, he wanted to bring science to the masses because that's where it belongs. The more people are interested in science and the more scientists the earth has, the more mysteries we will uncover.

When I was reading the wonderful book by Andrea Wulf on Humboldt, I learned that one of Humboldt’s first books was called Cosmos. I thought how appropriate that Carl Sagan, with his work Cosmos, perfectly echoes over time Humboldt’s notion that there is a wide world out there, and we need to see it to understand it. Not only to just learn about it for oneself but to make the world of scientific discovery better known. For example, the history of science is ripe with people like Sir Isaac Newton (who, as a physics teacher, I hold in great esteem), yet, he would often be more than happy to make a discovery and keep it under his bed and never share his findings. It is perfectly fine to figure things out for yourself, and hopefully, someone else brings it to life, but it contrasts with Humboldt's direct purpose of letting all this wonder be known.

Today, when we are driven by science more than at any other time in the history of mankind, we are also at a tipping point where fewer and fewer people understand the science that their life is utterly predicated on. It’s only going to get harder just because of the nature of science. We learn more every year than we learned the ten years prior, and that’s probably a gross underestimate. It’s only going to get harder to stay ahead of the curve. This is the reason why science needs to be brought to the masses as early as possible in a way that is accessible as possible.

I think this exhibition highlighting the life of Alexander von Humboldt and the work that the Smithsonian Institution does more broadly to pair art, science, and culture are excellent examples of this mission in practice.

Learn more about Alexander von Humboldt and the United States: Art, Nature, and Culture online!