Nine years after John F. Kennedy gave his speech, “The New Frontier,” Neil Armstrong became the first person to step foot on the moon. At the height of the Cold War, the American flag Armstrong raised claimed victory for the United States. The Soviet launch of Sputnik in 1957 had spurred the United States into action. The White House’s “Introduction to Outer Space,” published March 1958 outlined the justifications for undertaking a national space program: “The first of these factors is the compelling urge of man to explore and to discover, the thrust of curiosity that leads men to try to go where no one has gone before. Most of the surface of the earth has now been explored and men now turn to the exploration of outer space as their next objective.” Several months later, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, or NASA, was founded.

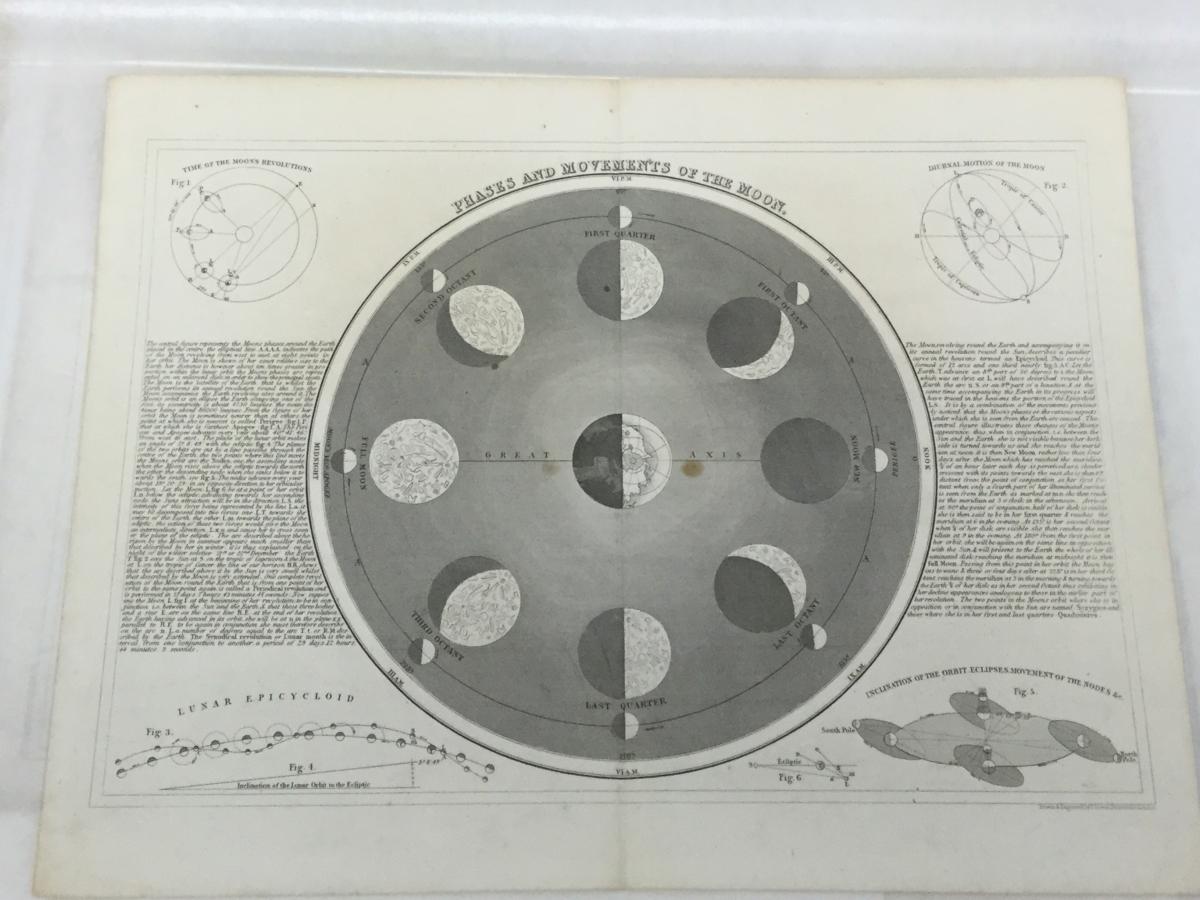

One of America’s most inventive and influential artists, Joseph Cornell, was keenly interested in these celestial explorations too. An avid amateur astronomer and pop culture aficionado, Cornell had been awed by the magnitude of the universe as a teenager and developed an appreciation for astronomy and stargazing that stayed with him throughout his life. He found inspiration in a variety of sources related to science. Magazines like Scientific American and antique maps of the moon and constellations equally captivated him. In the late 1950s, Cornell began a series of collages including Americana: Natural Philosophy (What Makes the Weather?) in which the “frontier” of interest was space.

In the mid-1960s, American popular interest in the solar system was growing, with news of astronomical discoveries and advancements in technology broadcast everywhere—from scientific journals to children’s books. The Space Age permeated society. Even on television, science fiction reigned supreme. The Twilight Zone debuted in 1959, and, in 1966, Star Trek’s intergalactic adventures were introduced. Each episode opened with the now iconic statement: “Space: the final frontier. These are the voyages of the starship Enterprise. Its five-year mission: to explore strange new worlds. To seek out new life and new civilizations. To boldly go where no man has gone before.”

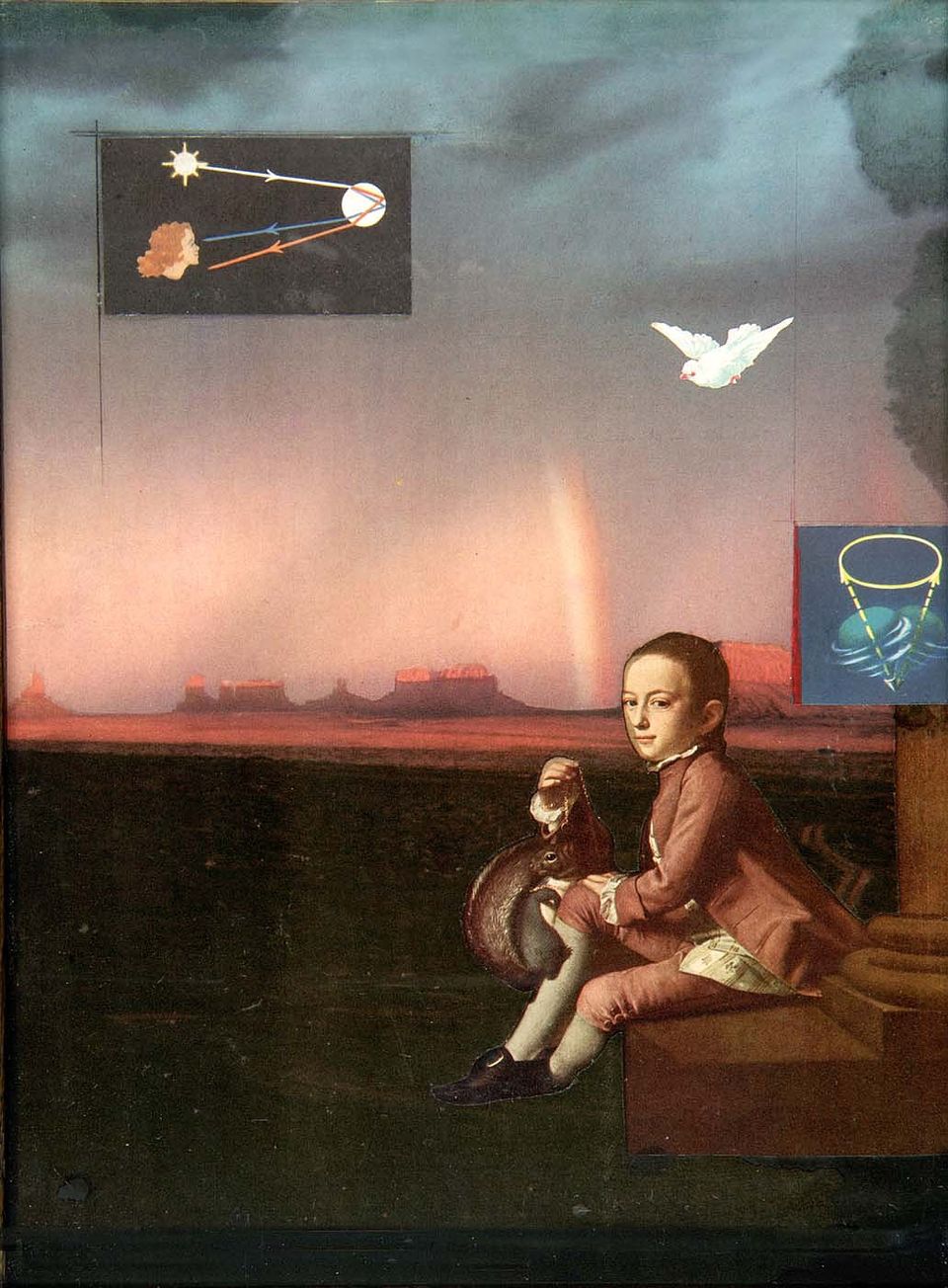

Americana: Natural Philosophy (What Makes the Weather?), currently on view in SAAM's permanent collection galleries, alludes to the nineteenth-century belief in Manifest Destiny, that it was the fate of the United States to expand westward. The collaged illustrations of scientific phenomena also reveal Cornell’s underlying and ongoing fascination with celestial discoveries of the modern era. Situated amidst a glowing southwestern landscape, a young boy appears to be sitting at edge of the western frontier. John Singleton Copley’s original portrait of the boy, Daniel Crommelin Verplanck, portrays the young colonial at his family country home in Fishkill, New York holding his pet squirrel—a sign of his urban, upper-class status. Copley, one of the preeminent American portraitists, primarily painted the wealthy New England elite before eventually relocating to England. Cornell admired Copley, considering him to be one of the first and best “American artists who worked out their own style of seeing.” With those two elements combined with the first part of the title, “Americana,” it is easy to read the collage as a celebration of America’s colonial triumphs—both in claiming independence from England and the fulfillment of Manifest Destiny a century later.

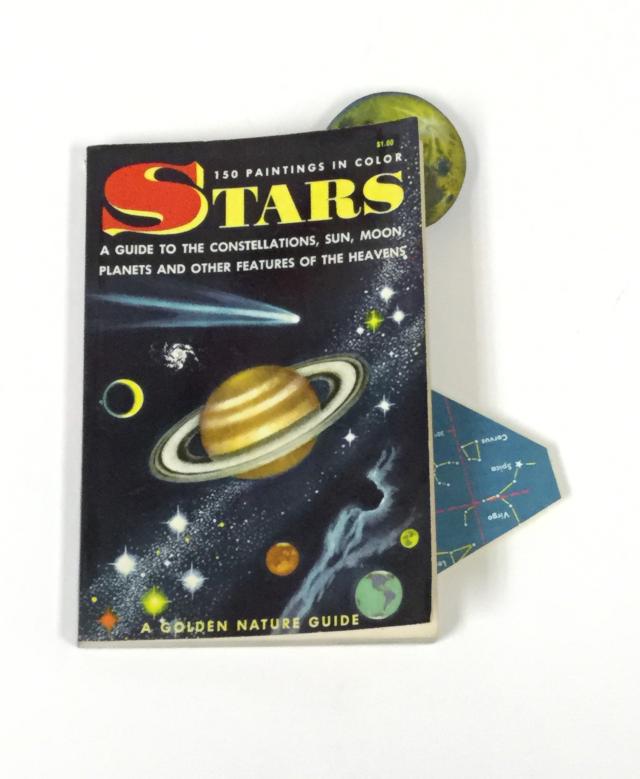

The cutouts are from The Golden Guides, a series of children’s books that featured simple illustrations to help the reader understand complex scientific concepts. In Americana: Natural Philosophy (What Makes the Weather?), the upper left illustration is from Weather: A Guide to Phenomena and Forecast. The book contains a section on rainbows that includes the diagram, which illustrates how rainbows are formed by light refracted by raindrops.

The second illustration along the center right edge of the collage illustrates the precession, or rotation, of the Earth due to the gravitational pull of the sun and moon on the Earth. Clipped from Stars: A Guide to the Constellations, Sun, Moon, Planets and Other Features of the Heavens, the illustration would have been of particular interest to Cornell due to its association with the discoveries of Albert Einstein, Isaac Newton, Galileo, Tycho Brahe, and Johannes Kepler, all whom Cornell greatly admired. Of particular note, Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity, which offers an explanation of why the moon orbits the Earth and why the Earth orbits the sun, was proven by the famed 1919 solar eclipse while 15-year-old Joseph Cornell was majoring in science at Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts.

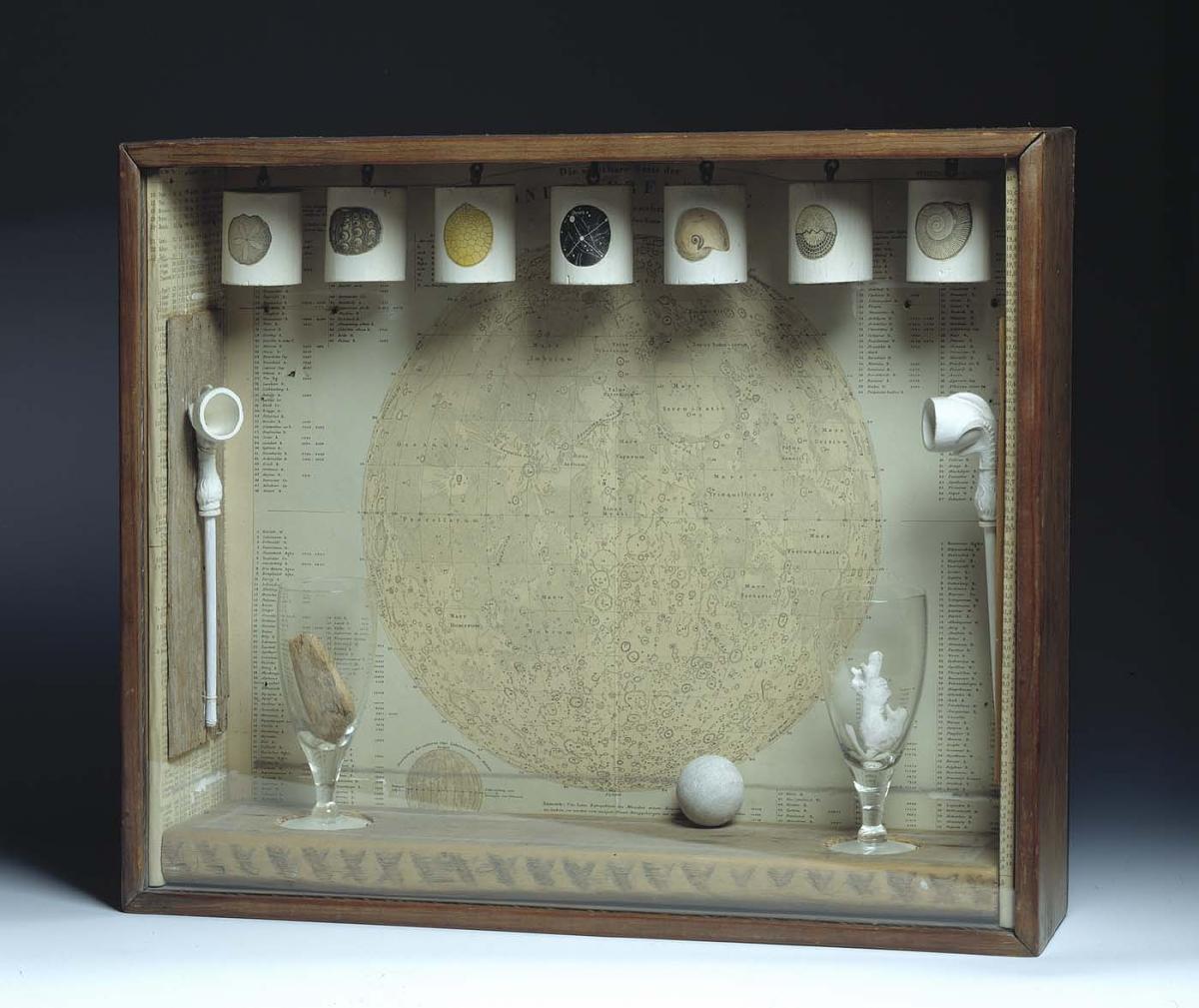

In some ways, Cornell’s artistic life was bookended by major scientific breakthroughs. From his earliest Soap Bubble Sets, which were certainly influenced by the 1929 confirmation of a rapidly expanding universe, to his late collages incorporating constellations and astrology, Cornell’s experiments in celestial navigation were very much a contemporary response to the rapid advancements in space technology and exciting discoveries of the twentieth century.

The Joseph Cornell Study Center at SAAM contains source materials and studio effects belonging to the late artist. The Study Center contains thousands of printed pictorial and textual ephemera and three-dimensional artifacts that served as both inspiration and raw material for Cornell's boxes, collages, and films.