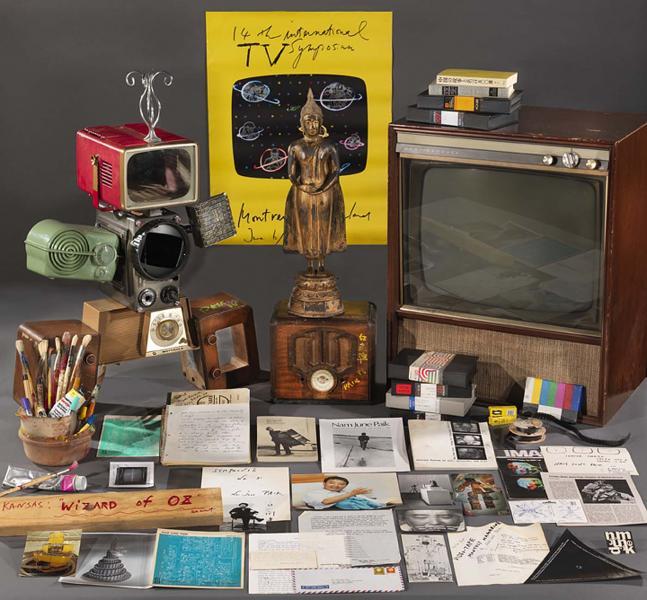

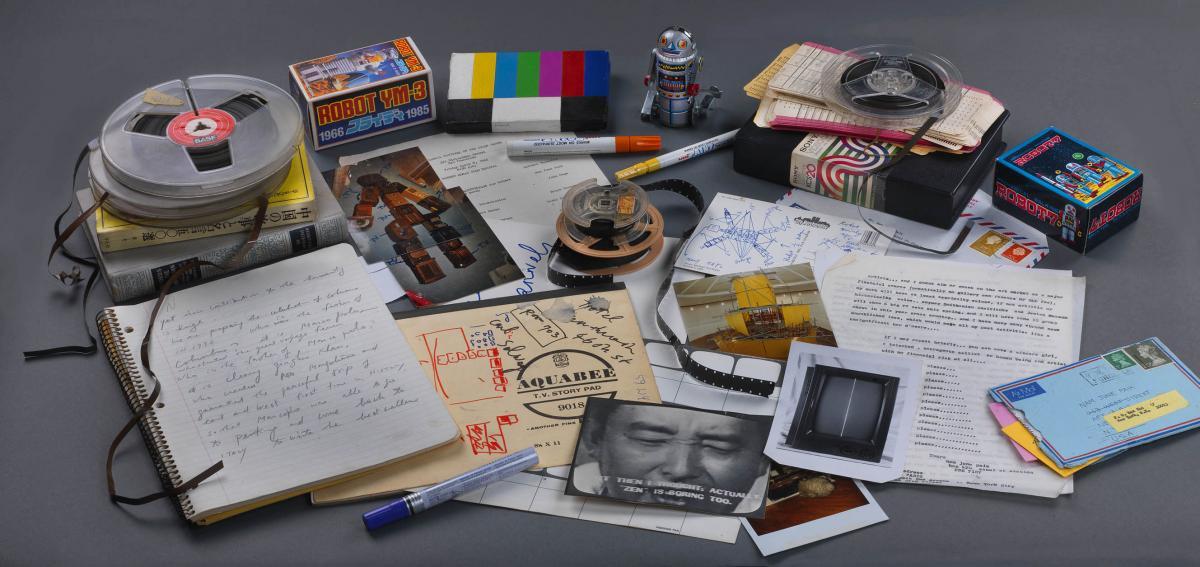

Since being gifted to SAAM by the Paik Estate in 2009, the Nam June Paik Archive has been an invaluable resource on this monumentally important artist. Scholars from around the world visit our Research and Scholars Center to explore the papers, photographs, artworks and objects that Paik amassed over a fifty year career, and curators at SAAM and beyond use these materials for exhibitions on Paik and his circle. Recently, selections from the Paik Archive became even more available to the public, when a book dedicated to his writings and a gallery at SAAM featuring his work appeared almost simultaneously.

On view from October 2019 until late 2021, “Off the Walls” is a newly installed collection-based gallery on SAAM’s third floor, where catalogues, flyers and videos from the Archive narrate Paik’s first decade in the United States. Also in October, MIT Press released We Are in Open Circuits: Writings by Nam June Paik, a collection of essays, project plans and correspondence from across Nam Jun Paik's career. Highlighting many previously out of print and unpublished materials, the book draws heavily upon works from the Paik Archive that, until now, would have required an appointment and a trip to DC to read. To mark this confluence, Hannah Pacious, SAAM’s Paik Archive collections coordinator reached out to Gregory Zinman, co-editor of We Are in Open Circuits and former SAAM fellow, to hear from him about his latest endeavors and his recollections working in the Archive. We’ll hear more from Gregory this summer when he stops by to celebrate this book and Paik’s birthday on July 15, 2020. Until then, enjoy these insights and come see what is on view at the museum!

As one of the earliest scholars to have access to the Nam June Paik Archive, you had an especially unique experience to explore a then “new” collection of archive materials. Can you tell me a little about your initial impressions and experiences?

Well, the first thing was realizing just how much material there was to look at. Fifty-five linear feet is a lot of paper to read through. So the volume of the Archive was a little imposing, to be sure. But I also figured that if there was that much to process, there might also be a bunch of things capable of surprising me, of challenging any preconceptions I had about Paik as an artist, of enriching my understanding of his methods and practice. I was also cognizant of the fact that I was in a privileged position—this was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to have the time, and really, the luxury, to read the writing of one of the most important postwar artists. Furthermore, I was would be doing so in the ideal academic environment, the SAAM fellowship, where I had a mentor, John Hanhardt, who worked with and was friends with Paik, who helped bring Paik to an American museum audience, and who represents one of the greatest individual repositories of knowledge on video art, and particularly, Paik’s art, there to guide me and give me feedback. The program also fostered a robust intellectual and social camaraderie among the fellows, which became so important in developing my research. Finally, I was beyond fortunate to have the resources of the Smithsonian at my disposal, and, in particular, the insights and patience of Christine Hennessey, and later, yourself, as I navigated Paik’s archive.

I also knew that I had to have some sort of plan for keeping track of everything. I went into my time in the Archive with the notion that I would be looking for information relating to Paik’s trio of satellite broadcasts in the 1980s—Good Morning, Mr. Orwell (1984), Bye Bye Kipling (1986) and Wrap Around the World (1988)—which I felt were under-scrutinized works in Paik’s oeuvre. I took a lot of notes, and I ended up starting a spreadsheet that grew and grew and grew until it had more than 500 entries detailing thousands of pages of material. That spreadsheet ended up being the key organizing document for what became We Are in Open Circuits.

Were there any discoveries that changed the trajectory of your research?

The most surprising thing, by far, was coming across Etude 1, a previously unacknowledged piece by Paik that turned out to be among the first works of computer art every made by an artist who had not been trained as a programmer. Paik made Etude 1 as an artist in residence at Bell Labs in 1967. He composed the piece in FORTRAN 66, a computer language that is no longer used, and ran it on a General Electric mainframe that no longer exists. The code as well as the resulting image—a series of concentric circles made up of the words DOG, GOD, HATE, and LOVE—were in the Archive, but they had not been recognized as comprising an original artwork. With the help of some computer scientist colleagues, I learned to read the code, and worked with a friend to rewrite the code in HTML5 so that we could see what the work might look like as an animation. It was thrilling to “discover” this work and bring it to light—Michael Mansfield, SAAM’s former curator of film and media arts, displayed Etude 1 as part of the exhibition Watch This! Revelations in Media Arts in 2015. As I’ve written elsewhere, however, such “discoveries” are not possible without the time, labor and knowledge of the people who collected, organized and made possible the materials in the Archive before any scholar sits down to start reading.

What were some of the most important findings that made their way into this book?

I know that I’m biased, but the book has so many wonderful documents that people can see for the first time outside an archive or collection: project plans like Electronic Opera from 1967—in which Paik outlines a new musical form made by computers and televisions before discursively imagining video telephone technology—computer medical instruments, facial and character recognition software and even the creation of synthetic faces. There is a handwritten page from Paik’s first draft to “Afterlude to the Exposition of Experimental Television,” the essay that accompanied his first solo show in Wuppertal in 1963, where you can see him crossing out and rewriting the text. That text came from MoMA, and we were able to show that alongside a typeset draft of the same from the Sohm Archive as well as the final version, a lithograph that was reproduced from the Walker Art Center. Taken together, you can see the progression of his ideas, and how carefully he reworked those ideas until they reached their desired expression. The last section of the book draws upon the Archive’s substantial collection of Paik's writings on Chinese history and philosophy, which have never before been published in English—the language he wrote them in originally.

How does this book tie into your other work/projects?

Well, I’m a media historian, and Paik plays a large role in my forthcoming monograph, Making Images Move: Handmade Cinema and the Other Arts (University of California Press, 2020), which seeks to rewrite the history of the moving image by considering the ways artists working across media—painted film, kinetic sculpture, light art, psychedelic light shows and video synthesis—attempted to extend the possibilities of abstract painting through motion, all without recourse to photography.

Paik also informs my next project, Screening Publics, which concerns Dara Birnbaum’s now-lost Rio VideoWall (1989), the first multi-screen public artwork in the United States. The piece was noteworthy for its technological innovation as well as for its home: the Rio Shopping Complex, a mall in Atlanta’s Old Fourth Ward. The artwork came to this predominantly black neighborhood via the queer spaces of New York City’s nightclubs, where Birnbaum found inspiration for the piece. Unfortunately, the VideoWall no longer exists today; when the mall was demolished, the artwork was destroyed. But its history can still be documented. Through interviews and archival research, the book exhumes the traces of this singular work and shows how writing the history of public art requires listening to public memory. I’m really excited about telling the secret history of video art in the clubs, where a tremendous amount of work—the bulk of which is, like the Rio VideoWall, lost—was being made seven days a week, alongside the pieces that were starting to be displayed in galleries and museums, but for very different audiences. Paik was one of the very first artists to make art from video walls, so his example will help uncover the story of how a technology of trade shows and theme parks became a medium for artistic expression. Screening Publics will be part social history of the diverse video artists of 1980s New York City, part excavation of the developing economic market for video art in the late 1980s, and part meditation on the care and preservation of digital artworks in the present.

Gregory Zinman is an assistant professor in the School of Literature, Media and Communication at the Georgia Institute of Technology. His writing on film and media has appeared in The New Yorker, The Atlantic, and October, among other publications. He has programmed film and media art at the Film-makers’ Co-op, the Museum of the Moving Image, Asia Society New York and the Ann Arbor Film Festival, as well as at number of venues in Atlanta. He is the author of Making Images Move: Handmade Cinema and the Other Arts (University of California Press, 2020) and co-editor, with John Hanhardt and Edith Decker-Phillips, of We Are in Open Circuits: Writings by Nam June Paik (The MIT Press, 2019).

The Nam June Paik Archive is open by advance appointment only.