In honor of Pride month, we're launching an occasional series where SAAM staff take a close look at meaningful works of art in our collection.

When you close your eyes and picture a gay bar, what do you see? Do you picture Stonewall, or perhaps a scene from Sex and the City? Maybe you picture drag queens or leather? I picture a collage of sorts, comprised of imagery from hundreds of memories. There are performers, silly wallpapers and décor, good drinks, bad drinks, friends, etc. On any given Sunday pre-COVID-19, you might have found me starting my day with brunch at the Duplex Diner on 18th Street in DC and ending it at Trade on 14th Street. I find I gravitate to these places, feeling the most unabashed and comfortable version of myself when I’m there.

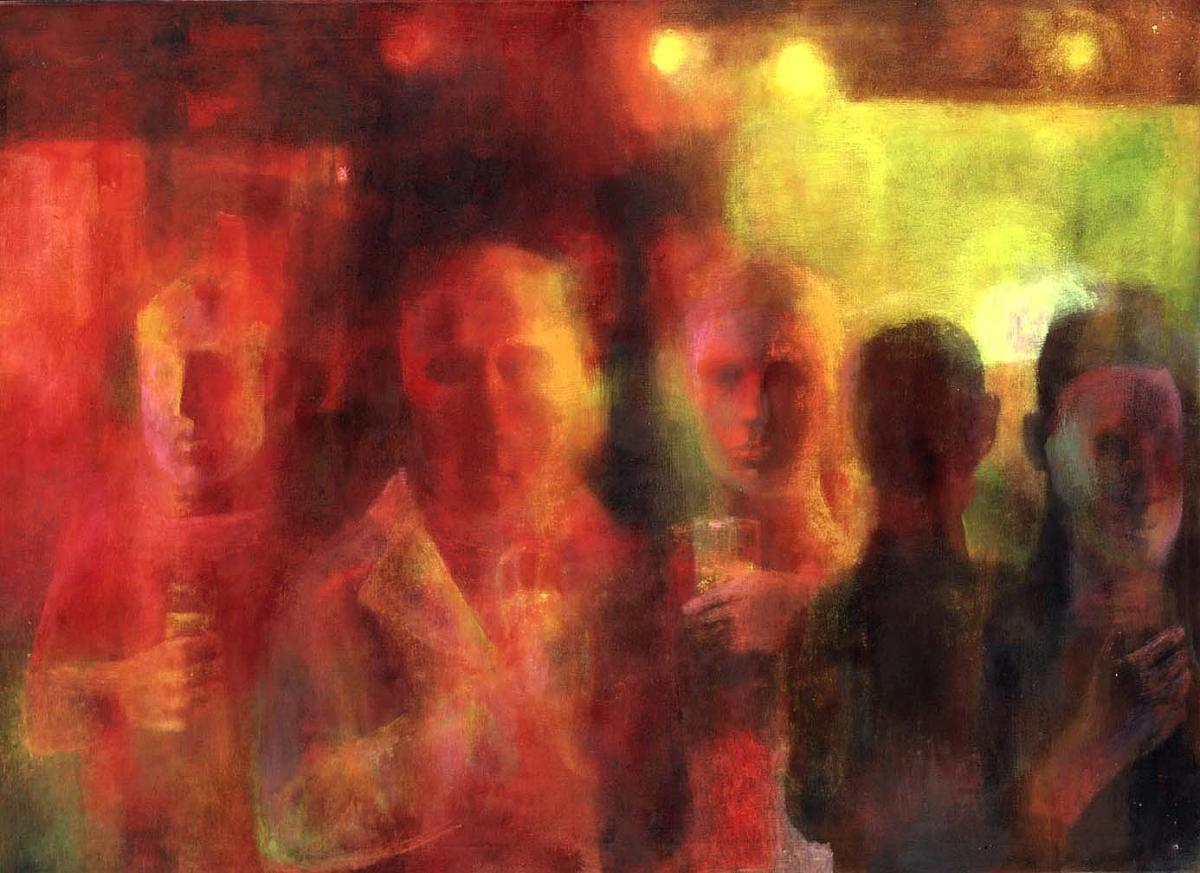

Consider this work titled The Bar, by Bernard Perlin. While I can’t say for certain that this work depicts a gay bar, we know Perlin was active in the 1950 gay bar scene of New York City. A WWII-propaganda and magazine illustrator, Perlin was an established artist who extensively created work depicting gay life. The nondescript figures in the painting are male-presenting and the limited choice of warm color suggests a level of unity, so it wouldn’t be outlandish to suggest the bar he is depicting might be a gay bar. In 1957, when Perlin painted this piece, the establishments he would have frequented would have catered (problematically) towards white, wealthy, “straight passing” men. Effeminate or gender-queer individuals were often excluded in order to mitigate the risk to the bar in the (likely) event of a police raid. During a raid, the more deniability the bar could have, the better. At this time, being gay was a felony in every state. Any area where gay men congregated were frequent targets for the authorities. Although straight people might have known about these places, they likely would have never entered one. The bars existed exclusively on the margins.

The term gay bar is somewhat of a misnomer—there is no one singular gay bar. Gay bars have existed in a variety of forms and are not homogenous. Throughout their history, they have held many purposes. They have served as places to find friends, love, alcohol, safety, and sex. A place to raise money and awareness for HIV/AIDS, and later, a place to host memorials for those in our community who fell victim to the illness. A place to host activist meetings. A place to dance. A place for community. Above all, a place to escape, the often oppressive, heterosexual world.

Contemporary gay bars exist for many of the same reasons and in some of the same forms. The physical threat to LGBTQ+ individual’s safety is ever-present. Just five years ago this Saturday, 49 people were killed during the Pulse Nightclub shooting in Florida. At the time, it was the largest mass shooting in the United States. Five years later—the pain and grief we have for those we lost has not subsided. In addition to the incomprehensible death toll, the attack on a place that was supposed to be a safe place for the LGBTQ+ community was devastating. Gay people carry this with them wherever they go. During the 2019 Pride March in Washington, DC, mass panic occurred when loud noises were mistaken for an active shooter. I ran for my life that day, along with hundreds of others thinking nightmares we all have had somehow manifested into reality. Thankfully, that incident was a false alarm, but no part of that experience felt distant from reality. The threats to the LGBTQ+ community are continuous. 2020 was the deadliest year recorded for trans and gender non-conforming individuals in the U.S. (HRC). This year alone, record numbers of anti-LGBTQ+ legislation have been introduced, fueling hate and intolerance. Our community needs dedicated LGBTQ+ spaces - if not for their significant cultural and historical heritage, then for the support they provide to the LGBTQ+ community.

Due to assimilation, gentrification, and dozens of other factors, the last twenty or so years have seen significant closures of gay bars. They have been appropriated—seen as places for a voyeuristic night out by people outside of the community or razed to make way for luxury condos. Some have closed due to declining patronage—the internet fostered LGBTQ+ connections free of physical limitations. Some individuals simply don’t feel welcome at bars for a variety of reasons—access, sobriety, discrimination within the LGBTQ+ community, etc. In 2020 alone—DC lost two gay bars. At the same time many have remained, or even opened in recent years—filling gaps left by closures and seizing opportunities to create more diverse spaces.

I’m not sure what’s next for gay bars. However, you’ll likely find me at one when I need to escape or I’m in a new city and need to find my footing. Perhaps I’ll be sitting next to the next Perlin—just as it was possible, he was sitting next to Jared French or Paul Cadmus at a gay bar in 1957. What is for certain, though—we haven’t seen the gay bar's final form, if there ever will be such a thing.

Andrew Rondinone is special events coordinator at SAAM.