Every year, we start planning SAAM Arcade by selecting a theme. We look for something that’s engaging, timely, and—most importantly—deeply related to the museum’s mission and collections. SAAM Arcade is about fun and nostalgia, but we also seek to ask deeper and more meaningful questions about the visual culture of our world. How do video games like Halo 2600 or A Slow Year fit into the story of American art?

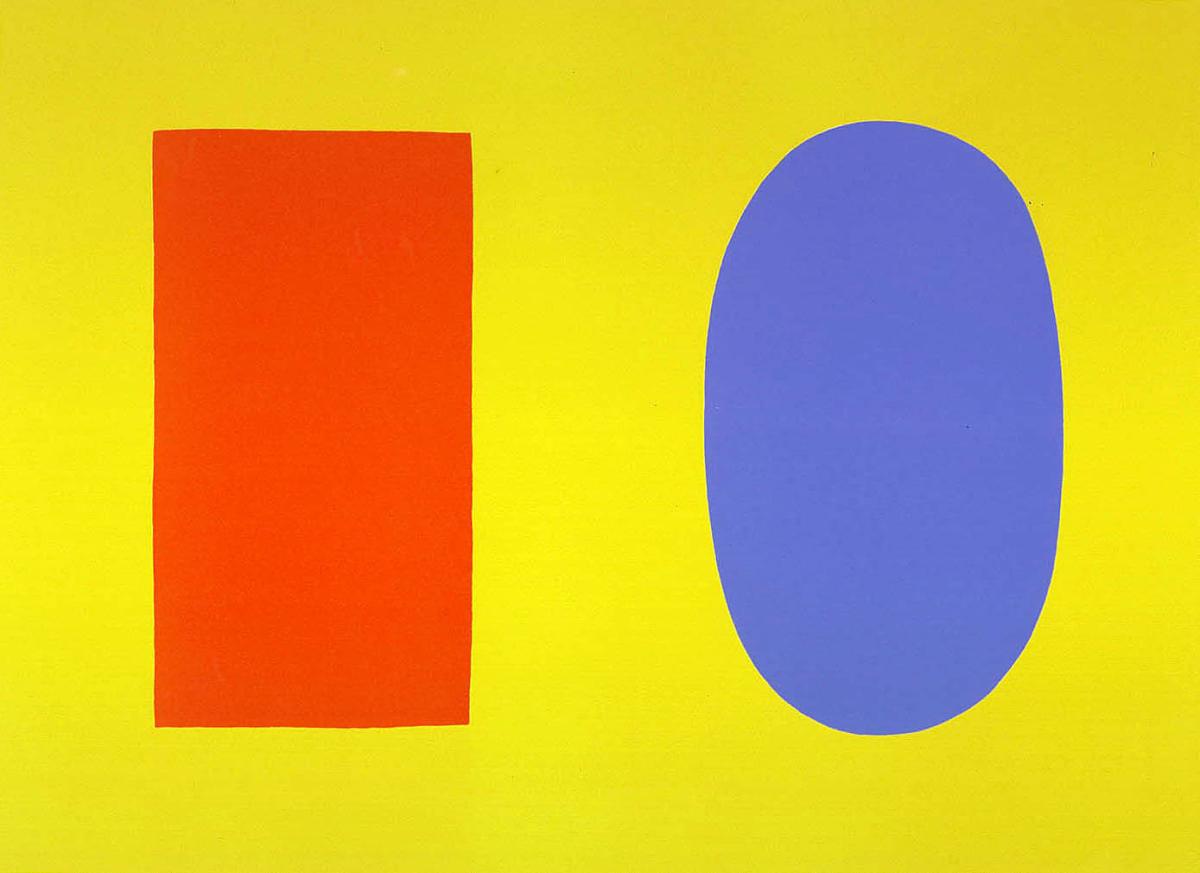

For the 2022 Arcade, we selected the theme “Color, Line, and Form.” We were inspired by the art scene of the mid-twentieth century, which saw artists experiment with the boundaries of artistic expression as they adjusted to a post-WWII world. Specifically, we drew inspiration from the work of American painter Ellsworth Kelly: in 1951, he created a series of studies—predominantly paintings and collages—centered around the concepts of line, form, and color. He proposed that these studies be compiled into a book and published, that the works within comprised “an alphabet of lines, forms, values and colors” that made up the most basic elements of art. While the idea of an art alphabet wasn’t new in the mid-twentieth century, Kelly and his fellow minimalists expanded on the notion that certain aspects of an artwork were essential and some were unnecessary; those unnecessary elements could be removed to reveal a more honest, objective work.

Whether or not you agree with the minimalists, it’s an interesting way to approach a work of art. What makes something art, or craft, or design? A painting has essential visual elements that add up to be more than the sum of its parts, but it also has a medium (for example, oil, acrylic, gouache) and a support (e.g: canvas, wood, masonite). Are those a part of the alphabet? It’s tempting to say they are not, but as we explore more complex ways of making art, the boundaries between the physical aspects of an artwork and its visual language grow thin. Minimalist artists like Dan Flavin and James Turrell used fluorescent lights or architectural spaces to create immersive works of art while contemporary fiber artists like Do Ho Suh or Bisa Butler employ needle and thread to express their artistic identities. An essential piece of performance art can be the artist themselves performing; an essential piece of video art can be the screen on which it’s shown.

It’s important to take the opportunity to step back and think about the parts instead of the whole. Part of the appeal of minimalism—of any abstraction, really—is that you’re forced to really consider what you see, to take time to dig into what the artist or maker or designer is trying to show you. When we talk about video games, we’re obligated to think about a much larger set of basic elements—line, color, and form are present alongside code, interaction, and parameters. Without diving into the inscrutable world of ludology, what can an average person expect to find if they boil down a video game into its most basic forms? Code, certainly. Color, perhaps. But what about fun? Games like That Dragon, Cancer and Gone Home (and if you’re not into self-punishment, any Dark Souls title) would suggest otherwise. What about invoking an emotional response? I’d say that anyone who has ever mindlessly played Candy Crush or Tetris while they watched TV or rode the subway would disagree.

A game like Pong seems quintessentially minimal, but we also recognize in its mechanics and visuals something familiar and comforting: ping pong. Even a massively complex triple-A title like Call of Duty or a constantly-evolving MMORPG like World of Warcraft are made up of those same basic elements, the same skeletal structure beneath the final product (elaborate or otherwise). If we accept that video game design is an artistic medium just like painting or sculpture, then it follows that new terms may need to be added to our artistic alphabet.

This year, we’re inviting museum visitors to engage with artists and debate these terms themselves by attending the Arcade, playing new and old favorites, exploring the collections with a special scavenger hunt, and making their own games online. The program will include works by eight independent developers from around the world showcased alongside modern and vintage consoles and arcade cabinets.

SAAM Arcade 2022: Color, Line, and Form will take place on July 30 from 11:30 a.m. to 7 p.m. at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, DC. The 2022 SAAM Arcade Game Jam will be hosted online at AmericanArt.itch.io. This program is sponsored by Events DC. For more information about SAAM Arcade, please visit AmericanArt.si.edu/arcade.