SAAM marks and mourns the passing of Richard Hunt, who died on December 16, 2023. For nearly five decades, Hunt ranked among the foremost American sculptors. His abstract creations, executed in welded and cast steel, aluminum, copper, and bronze, make frequent reference to plant, human, and animal forms. Hunt self-identified as a "Midwestern sculptor," and he remained famously committed to his hometown of Chicago, where he made his life and career. Upon Hunt’s passing, President Barack Obama declared the sculptor “one of the greatest artists Chicago ever produced.”

He played a leadership role as a Commissioner at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (1980-1988) and on the Smithsonian National Board (1994-1997). Charles C. Eldredge, former director at SAAM, remembered Hunt as a member of the board “who always exercised a quiet but vital voice in debates.…A thoughtful and valued contributor, smart as well as wonderfully skilled in his art.”

Hunt was born on September 12, 1935, the younger of two children of Howard and Inez Henderson Hunt, a barber and a librarian respectively who lived on Chicago's predominantly Black South Side. Both of Hunt's parents provided formative influences during his childhood. He acquired an early interest in politics from conversations he overheard while working in his father's barbershop. His mother instilled a love of reading and classical music and took him to local Black opera companies.

Hunt began drawing as a child, and he enrolled in a summer program at the Junior School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where he received his initial training in sculpture under Nelli Bar. In 1950, Hunt set up a studio in his bedroom and began to model in clay. One of his earliest influences was the work of Spanish sculptor and painter Julio González, whose work he saw in the exhibition Sculpture of the Twentieth Century, held at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1953. Within two years Hunt had taught himself the welded-metal technique.

In 1955, Hunt attended the open-casket funeral of Emmett Till, the young Black Chicago native who was murdered and mutilated by white men, a searingly transformational experience that fortified his social and racial consciousness.

As Hunt’s work evolved throughout the 1950s and 1960s, he received many awards, opportunities, and accolades. In 1957, he was awarded the prestigious Logan, Palmer, and Campana prizes, and the James N. Raymond Foreign Traveling Fellowship, which supported his travels to England, France, Spain, and Italy. Hunt was a Guggenheim Fellow in 1962, a Cassandra Foundation Fellow in 1970, and a Tamarind Fellow (awarded under the auspices of the Ford Foundation) in 1965. He was featured in numerous one-man and group exhibitions, received several honorary degrees, and served as a visiting artist and professor at many schools and universities. In 1969, Hunt became the first African American sculptor to be honored with a retrospective exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. By this time, Hunt was frequently utilizing automobile junkyards as his quarries, and transforming cast-off automobile bumpers and fenders into elegant abstract welded sculptures.

More than thirty examples of Hunt's sculptures can be found in and around Chicago's libraries, community centers, universities, apartment houses, and office buildings. Many other works may be seen throughout the Midwest, South, New York, and here in Washington, DC. Visitors to the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture will encounter Hunt’s soaring Swing Low upon entering the museum’s lobby. Elsewhere in DC, Hunt’s striking Freedmen's Column adorns the campus of Howard University.

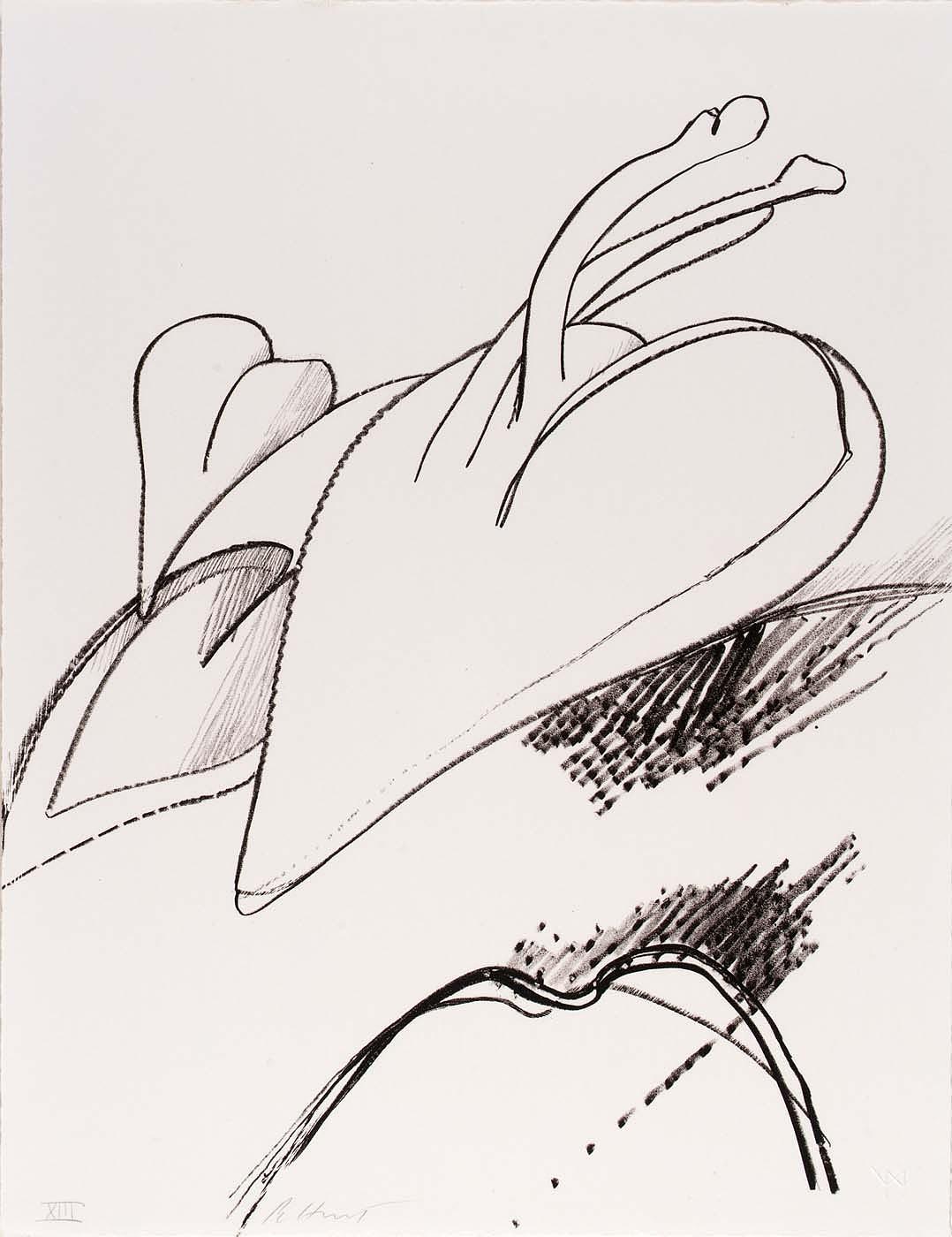

SAAM proudly holds twenty-one examples of his work, including three sculptures and to eighteen lithographs, some of which served as studies for his outdoor sculptural projects. The largest and earliest sculpture by Hunt among SAAM’s holdings, Plant Form (1956) characteristically and beautifully merges naturalistic forms and industrial material (steel). The sculptor created "The greatest obstacle to being heroic is the doubt whether one may not be going to prove one's self a fool; the truest heroism, is to resist the doubt; and the profoundest wisdom, to know when it ought to be resisted, and when to be obeyed."—Nathaniel (1975) for the Great Ideas project, a program that commissioned artists to interpret the writings of the world’s eminent thinkers. Hunt’s title in this instance invokes a passage from Nathaniel Hawthorne’s novel, The Blithedale Romance (1852). Study for Richmond Cycle (1977) is a model for a monumental plaza sculpture outside the Social Security Administration building in Richmond, California. Composed of two distinct parts that are separated spatially but united visually by virtue of shared materials and surface finish, the sculpture evokes the cycle of life in which age and the weight of experience are accompanied by the lightness and promise of youth.

This tribute was adapted from Regenia A. Perry's Free within Ourselves: African-American Artists in the Collection of the National Museum of American Art and includes contributions from Karen Lemmey, the Lucy S. Rhame Curator of Sculpture.