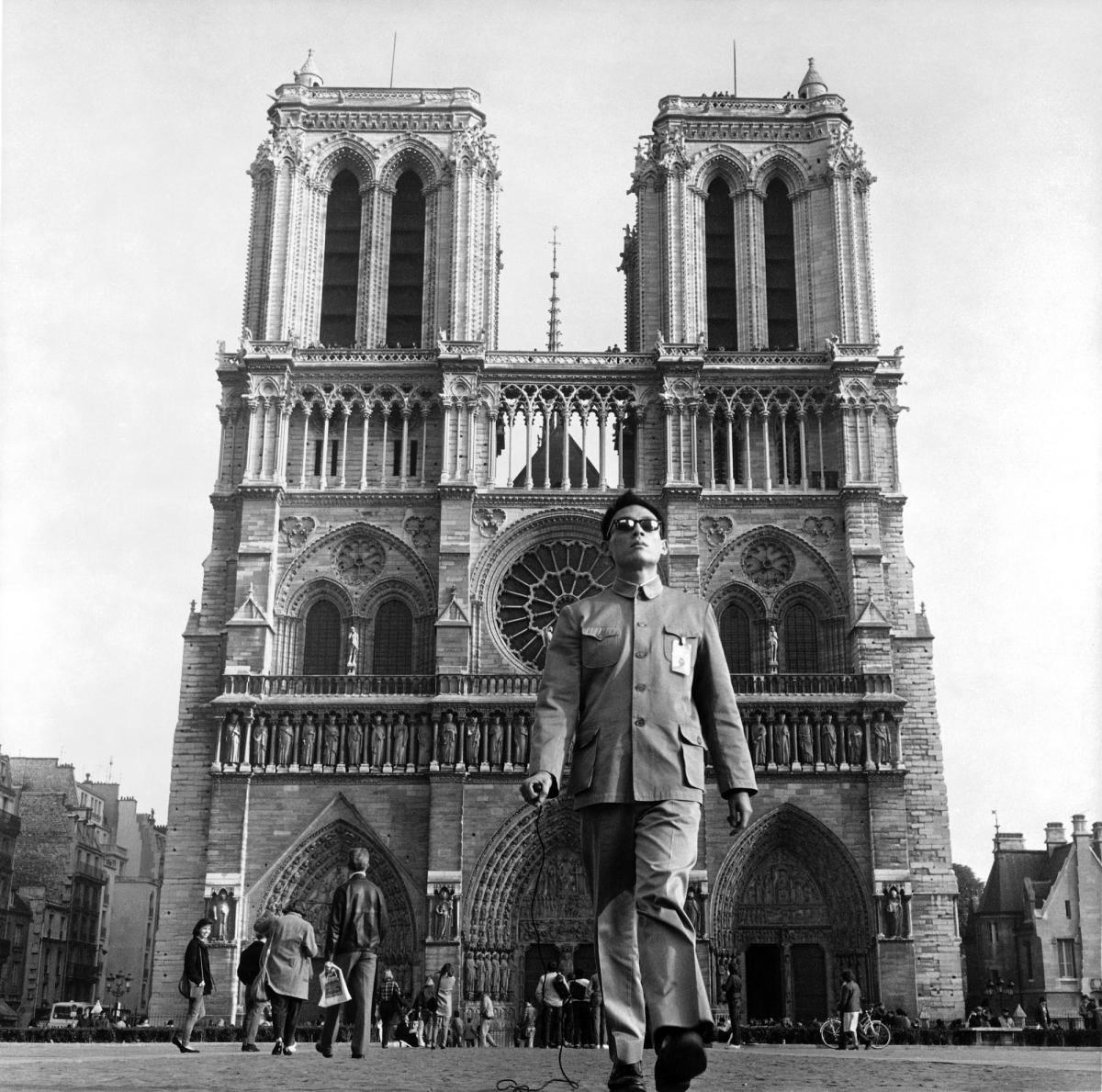

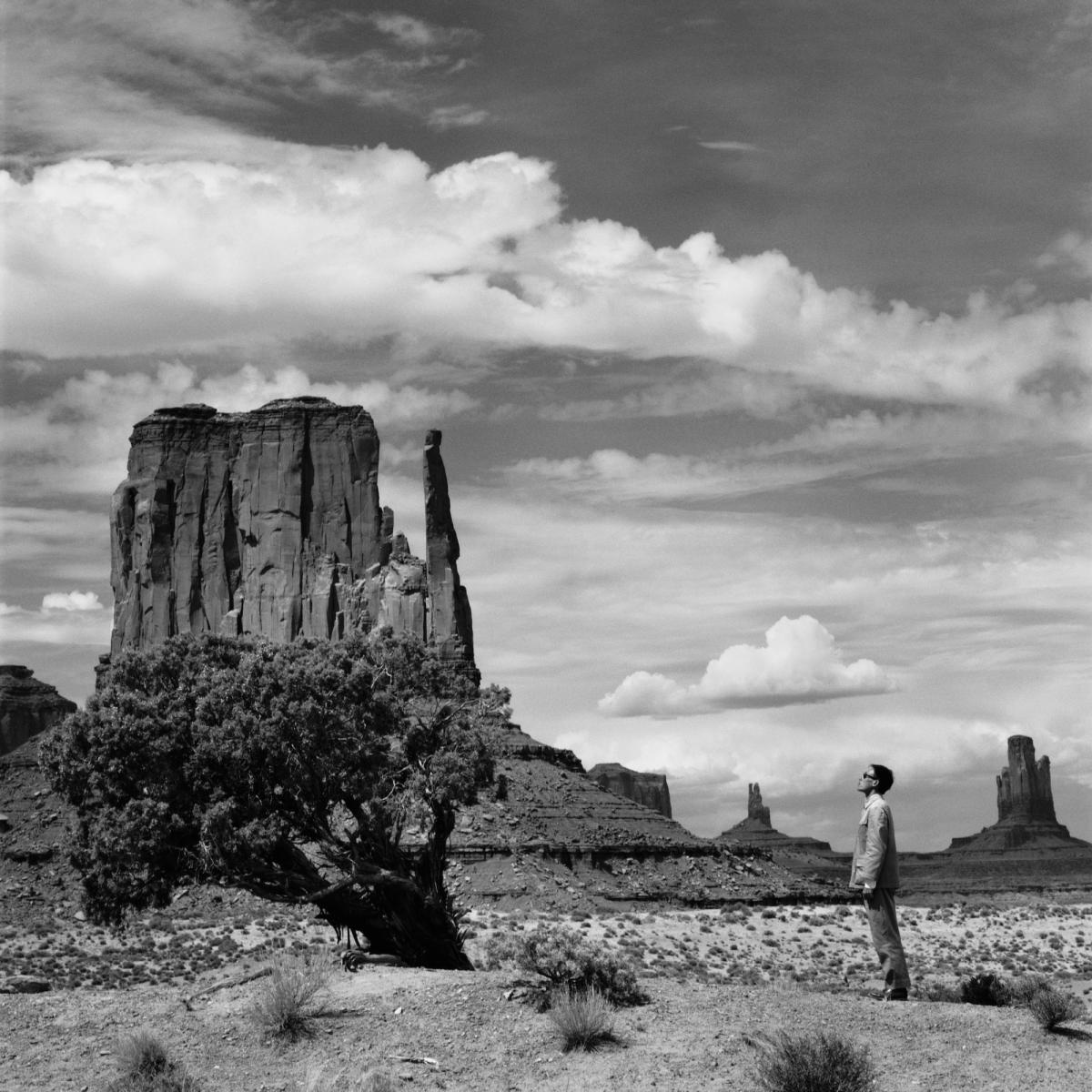

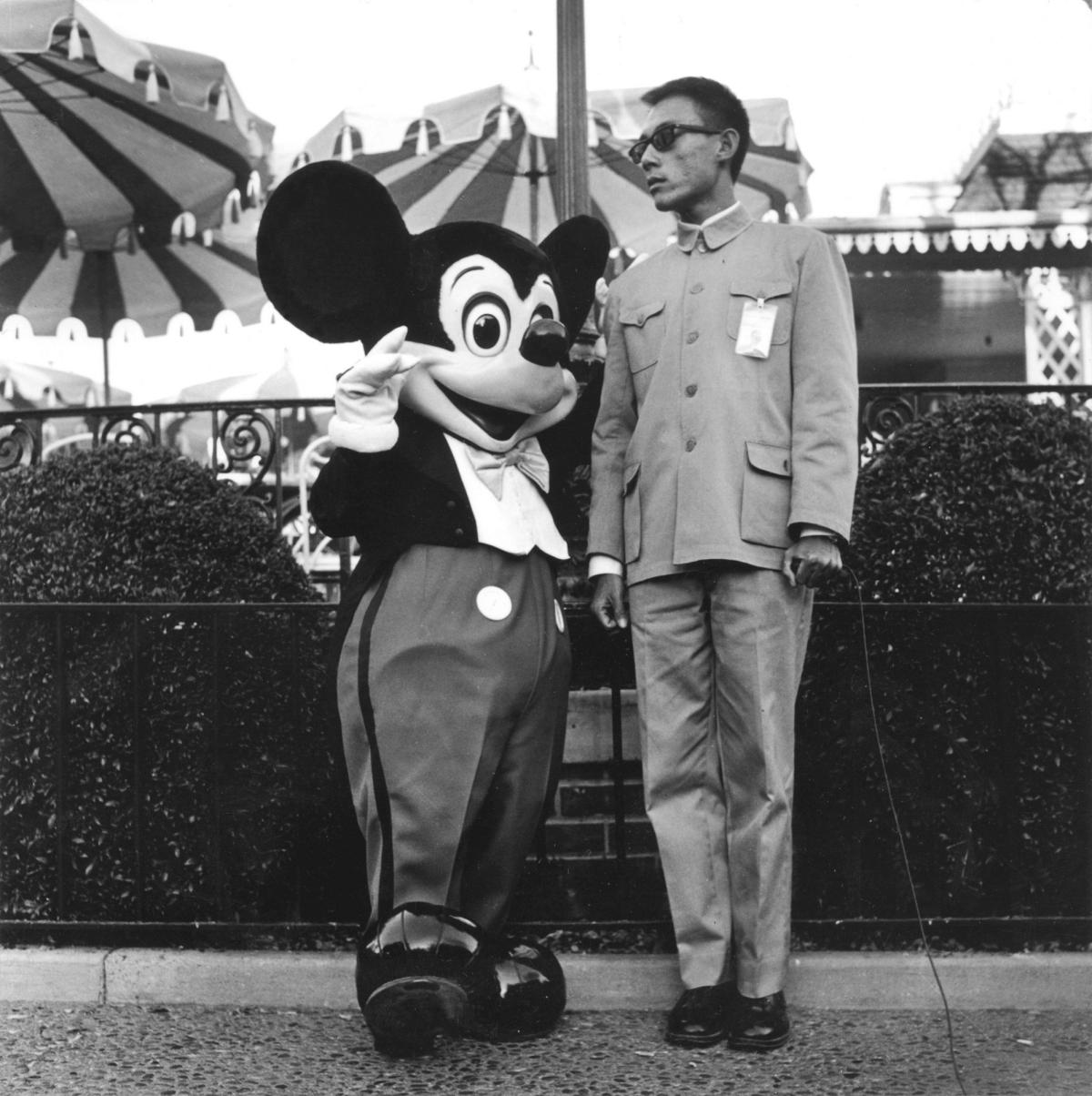

In 2021, SAAM acquired six photographs by Tseng Kwong Chi from his signature series East Meets West. In these images Tseng inhabits a persona he referred to as the “Ambiguous Ambassador.” Wearing a Mao suit (the grey uniform associated with the Chinese Communist Party) and mirrored sunglasses, he poses next to landmarks and monuments, many of them emblems of American national identity. Like the Untitled Film Stills of Cindy Sherman—also produced in the late 1970s—East Meets West is a groundbreaking photographic work that illuminates the changeable and socially constructed nature of identity. It is also a rare piece of conceptual art to specifically reflect on the racialized experiences of Asian people in the United States. When I first encountered one of Tseng’s images in the late 1990s, I felt a jolt of recognition. It was startling to stumble across a work of art that so precisely confirmed my lived experience as a person of Chinese descent in late-twentieth-century America.

According to his sister, the dancer and choreographer Muna Tseng, Tseng’s first performance as the Ambiguous Ambassador happened by accident. While visiting their children in New York City in the late 1970s, Tseng’s parents decided to treat Muna and Kwong Chi to a meal at Windows on the World, the restaurant at the World Trade Center. Muna recalls:

“Since the dress code was suit and tie, and he didn’t have a suit and tie, he showed up in this uniform [the Mao suit].... The maitre d’ took one look at him and treated him like a VIP, like a dignitary.”

China and the United States were then working to normalize diplomatic and trade relations after decades of estrangement. Perhaps having seen images of Vice Premier Deng Xiaoping in his Mao suit being toasted at the White House, the maître d’ was eager to welcome this unexpected emissary from the East. In their eyes, no doubt, Tseng’s racial features authenticated his costume. A Chinese man in a Chinese uniform would seem to present a hyper intelligible identity to the world, one in which race, culture, and nationality are unambiguously aligned.

The reality of Tseng’s multifaceted and transnational identity was far more complicated. An irony of what became Tseng’s career-long adoption of the Mao suit is that his father had served in the Chinese Nationalist Army against the Communists and fled the mainland for Hong Kong after the Revolution in 1949. Tseng himself never set foot in Communist China, having been born in Hong Kong in 1950 and emigrated with his family to Canada in 1966. As an adult, Tseng moved to Paris, where he studied photography and, in 1978, to New York City. There he found his niche in the burgeoning East Village art scene, in particular, among the groovy, gender-fluid cohort that congregated at Club 57. Sociable and high-spirited, Tseng formed close friendships with fellow artists Keith Haring, Ann Magnuson, and Kenny Scharf. As for the Mao suit, it was a thrift-store purchase, bought by Tseng in Montreal.

Tseng’s history of displacement and migration would not have been apparent to the restaurant host at Windows on the World. They saw, simply, a Chinese—someone of and from China. Such a conclusion is not surprising, for to be Asian in America is to be constantly reminded of the abiding significance of one’s origins. “What are you?” people commonly ask—or (and this is meant to be the same thing), “Where are you from?” Despite ongoing challenges to essentialist conceptions of race, the belief still lingers that racial identity is fixed and can tell us something significant and true about an individual. Certainly in the 1970s, but even to a surprising extent today, racial identity for people of Asian descent in the U.S. has been equated with profound foreignness.

For a stranger to quickly assess Tseng as “Chinese” and assume other details of his identity from there, was therefore not unusual. What was unusual, and surely amusing to Tseng, was that racial stereotyping, in this instance, had netted him preferential treatment. At a moment of high excitement about Sino-American relations, Tseng in his Mao suit was received “like a VIP, like a dignitary.” Paradoxically, by allowing his identity to be read reductively through his race, and by accentuating rather than attempting to mitigate his visible “foreignness,” Tseng found a way to achieve the status of honored guest rather than marginalized immigrant.

A gay man, Tseng was well-aware of the signifying power of dress, gesture, and posture. His donning of the Mao suit can be understood as racial camp—a playful, self-protective maneuver that did not prevent Tseng from being misinterpreted but did allow him to take control of the manner of the misreading. To those who perceived the levity with which Tseng wore the suit, something was revealed about his ironic sensibility. The dissonance of his appearance—the fact that the suit looked both “natural” and “unnatural” on him was not effaced but highlighted, at least to the knowing beholder. But when people were unable to see past type, the misconception did not come at the cost of Tseng’s psychic humiliation.

Tseng went on to create roughly 150 images comprising East Meets West. His performance of “Chineseness” in these photographs reveals his acute awareness of the stereotypes of Euro-American Orientalism. His blank, robotic demeanor in images such as Disneyland, California invite stock associations of the Chinese as “Yellow Peril,” and the repetition of this pose in numerous photographs would seem to tap into White America’s century-long dread of being overrun by Asian immigrants. In other images, Tseng’s stylishness and humor come through—some of the earliest photographs picture him coolly strolling the boardwalk and beaches of the popular gay vacation spot of Provincetown, Massachusetts, appearing more like a character from a French New Wave film than a visitor from the People’s Republic of China. The shutter release Tseng plainly grasps in many pictures reminds us that he is the author of these varied depicted realities; that, even as he presents himself to the Orientalist gaze, he is in command of the means of representation. Given that racial identities circulate and perpetuate via staged images—and that European American assumptions have traditionally driven those images—this is a significant gesture.

Tseng’s art was prompted by and embedded in live social relations. It is this trait—its sense of performance—that accounts for its power. Performativity allows us to see art as consisting of social actions and reactions, not just collectable objects; and it authorizes artists to engage with real-world conditions of representation. Something was at stake for Tseng when he put on the Mao suit in public. The guise of the Ambiguous Ambassador was calculated artistic strategy, but also lived experience—a performative act with the power to affect genuine social disruption.

Looking at Tseng’s images today, I find them funny, sad, and inspiring all at once—and it makes me wonder how young Asian Americans, growing up at a different geopolitical and social moment, apprehend them. Have the racist and xenophobic stereotypes Tseng satirizes in East Meets West become unrecognizable? If this is ever the case, it will be thanks to generations of people who, like Tseng, reject conventional codes of identity and insist on new, ambiguous conditions of being.