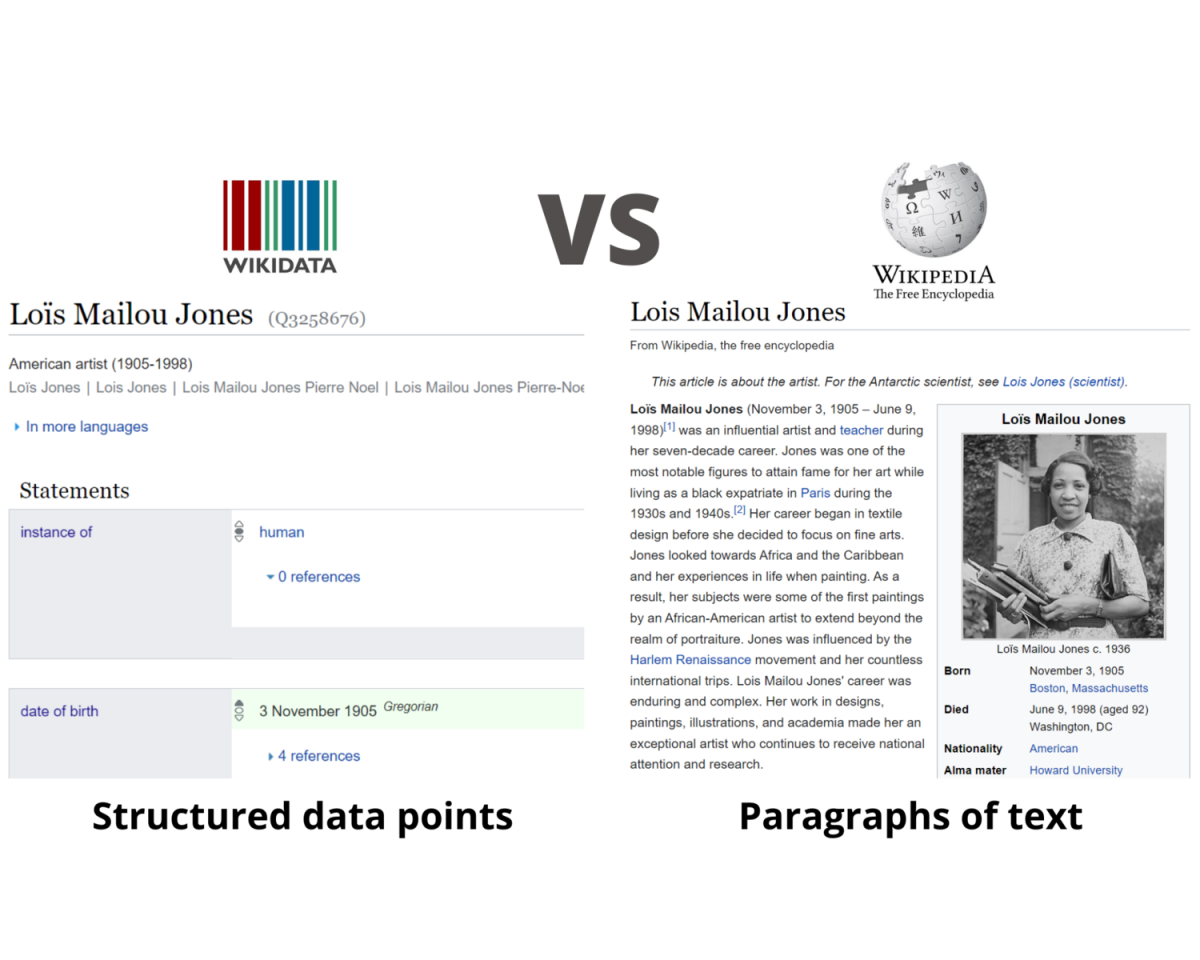

Wikipedia, the online encyclopedia that launched a thousand term papers, has become a fixture in our lives, but there is a lesser known database equivalent, Wikidata. Whereas Wikipedia contains articles written in complete sentences, Wikidata stores data points, like the date of birth for a person or the name of a director for a movie. SAAM and Smithsonian Libraries and Archives are adding all SAAM artist names to Wikidata–but why? More importantly, what does this mean for artists identified or identifying as women?

Artists have rich identities beyond SAAM; sharing the data we have to open platforms like Wikidata builds a web of knowledge–interconnected data points that link people to more and more related information. This is particularly important for women, who for many reasons, are under documented in books, museums, and archives.

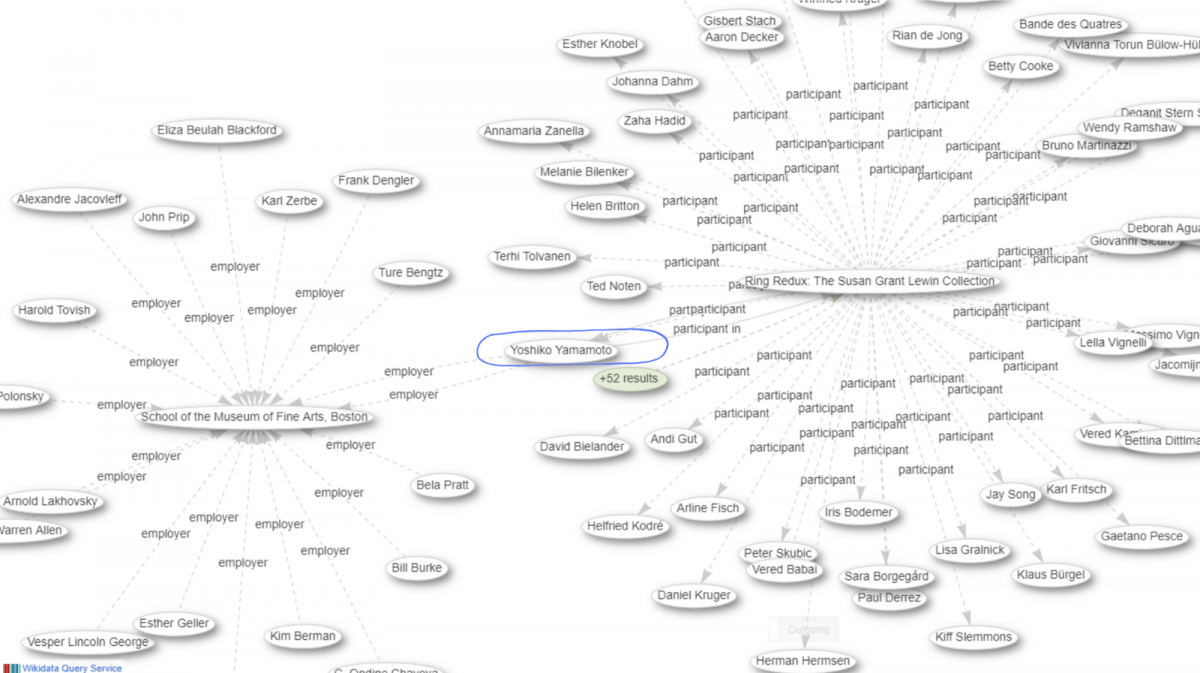

Take Yoshiko Yamamoto, a Japan-born American jewelry artist, for example. Once SAAM data about Yamamoto was uploaded to Wikidata, other people interested in Yamamoto found the information and linked more data to the artist, including other collections featuring Yamamoto’s work such as Ring Redux: The Susan Grant Lewin Collection. “Yoshiko Yamamoto” is a common name; it’s shared by a well-known athlete and a popular printmaker, both of whom are more visible than the jewelry artist on the web. Publishing what we know about Yamamoto in Wikidata, which feeds data to search engines like Google, helps people looking for Yamamoto distinguish the artist from others as well as puts Yamamoto in community with related people and topics.

SAAM's staff and visitors also benefit from the information shared in Wikidata. For example, artist Daisy Hooee Nampeyo has a robust Wikidata presence and a Wikipedia article. Bringing SAAM together with this Wiki universe connects us to information we don’t have to enhance our understanding and that of our visitors.

The veracity of data points in Wikidata is sometimes debated, and incorrect or misleading information can spread quickly on the internet. Citing reliable references is preferred, and people can see references for themselves to decide if the information is trustworthy. Yet Wikidata, which tries to balance open participation with quality, sometimes perpetuates existing power structures by privileging certain types of documentation over others. For example, unrecorded oral history or taking the focal person’s “word for it” are not acceptable references, yet the gender normative practice of inferring that someone is female or male based on their name is. These limitations, however, aren’t necessarily a stop light: they can help us think of ways to transform Wikidata into a more worthy platform for women’s history and additional marginalized histories.

Sonoe Nakasone is a data specialist with SAAM and the Smithsonian American Women’s History Initiative.