Watch This! Revelations in Media Art

The second half of the 20th century introduced an array of technologies and electronic phenomena that set art in motion. Innovations in high-fidelity stereo, broadcast television, videotape and satellite technologies contributed to the frenetic pace of social change through the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s, simultaneously shattering and shaping modes of communication and expression. From the ’80s into the millennium, the electronic age burst into the digital age, opening entirely new terrain for creative exploration. Artists have fearlessly engaged these technological leaps, finding in them new modes of expression that continuously defy and redefine the boundaries of “art.”

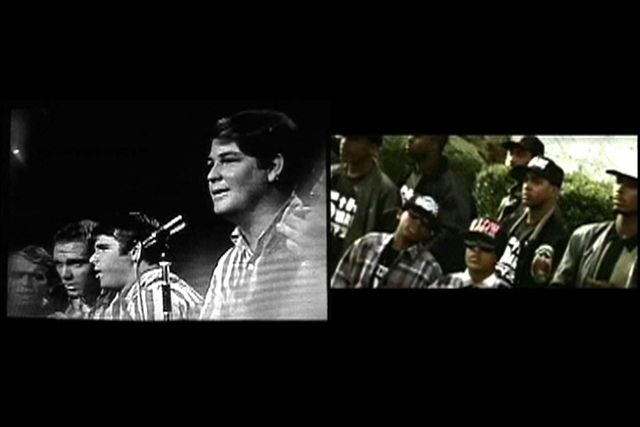

Watch This! Revelations in Media Art presents pioneering and contemporary artworks that trace the evolution of a continuously emerging medium. The exhibition celebrates artists who are engaged in a creative revolution — one shaped as much by developments in science and technology as by style or medium — and explores the pervasive interdependence between technology and contemporary culture. The exhibition includes 44 objects from 1941 to 2013, which were acquired by the museum as part of its longstanding commitment to collecting and exhibiting media art.

Description

Watch This! includes major works by artists Cory Arcangel, Hans Breder, Takeshi Murata, Bruce Nauman, Raphael Montañez Ortiz, Nam June Paik, Martha Rosler, Eve Sussman, Bill Viola and others that highlight the breadth of media art, including 16 mm films, computer-driven cinema, closed-circuit installations, digital animation, video games and more.

Two video games—“Flower” (2007), by Jenova Chen and Kellee Santiago and “Halo 2600” (2010) by Ed Fries—represent a rapidly-evolving new genre in media art. Both will be on view for the first time since the museum acquired the games in 2013 . The museum is a leader in identifying video games as an art form, and it was one the first museum in the United States to acquire video games as part of its permanent collection, marking a commitment to the continuing study and preservation of video games as an artistic medium.

An exciting highlight in the exhibition is the debut of two newly uncovered works by Paik, considered the “father of video art.” An early FORTRAN computer program—the existence of which was previously unknown—developed by Paik with Bell Labs, and an early rendition of one of the artist’s famed “TV Clocks” that was long thought lost, were discovered in the artist’s archive after it was acquired by the museum in 2009. The exhibition is the first time the FORTRAN program and its related print have been exhibited to the public.

Archival materials related to the artworks on view expand on the varied and unorthodox practices among media artists. Schematic diagrams, correspondence, storyboards and other ephemera that shed light on the engineering behind custom-built electronics, broadcast performance pieces and pioneering computer programs are included in the exhibition.

The exhibition is organized by Michael Mansfield, curator of film and media arts.

Visiting Information

Videos

Watch This! Revelations in Media Art - Exhibition Essay

_MEDIA, ART

The Big Business Man smiled. "Time," he said,

"is what keeps everything from happening at once."

Raymond Cummings, The Girl in the Golden Atom. 1922

In the 21st Century: Innovation is old news. Invention lacks originality. These conventions are so readily applied to readings of American history as to become banal. Indeed this entire socio-political structure — the very birth of the nation — was an innovative and new invention. It is ironic then, that writing any account tracing achievement through the lens of invention is maybe not all that inventive. It creates nothing new. Applying innovation as a means to understanding the evolving shape of contemporary culture gives us no better means of understanding culture in the present. It would be unimaginative. Art and artists too have long engaged the most advanced materials and techniques afforded them, inventing new strategies and devices that may better express their creative vision. So what that these defining expressions index the health and vibrancy of what must be an extraordinary experience? After all, invention and innovation in the artist's practice are also matters of settled tradition.

These conventions are clearly reflected in traditional arts such as painting, sculpture, photography and craft — each one an accepted expressive medium that incorporates the contemporary materials of their day — throughout the history of art not only in America, but also well beyond. Sculpture regularly assumes new materials and techniques, from direct carving to casting, pointing and assemblage. Painting is both a verb and a noun, and reinvents itself at every turn. Photography once employed mammoth glass plate negatives and now no negative at all. These incremental, procedural changes in traditional media leave them yet static. They still produce paintings, sculptures and photographs. This is certainly not to suggest that there is no merit in considering these material evolutions, or that reconsidering them in time provides no valuable cultural insights. All art is revealing. Rather, it can be said that these traditions in art sit motionless. And they did so through the first half of the 20th century. The second half of the 20th Century exploded these traditions, both figuratively and literally, giving rise to a staggering array of tools, technologies, and communications phenomena that sent humanity careening down a path of relentless acceleration toward futurity, and with it, set art in motion.

What follows here is a primer on the material and conceptual exchange with technology that is shaping artistic practice. It accompanies the exhibition Watch This! Revelations in Media Art, and outlines the organizing principals for a gallery of time and technology based art practices. Watch This! is an introduction to media art drawn from the permanent collection at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Its arrangement is an invitation to examine a broad spectrum of technology-based works of art in dialogue with — and within sight of — one another. The immense range of materials is both a testament to the fantastic advancements in electronics and a spectacular critique of the cultural meanings embedded in them. This not only highlights the pervasive interdependence between contemporary culture and technology, but also introduces the means in which art largely possesses and reconceives itself in the technological forms and relations of the present.

Advances in technologies and human ingenuity that were necessitated by the Second World War precipitated an enormous surge in demand for consumer electronics that followed. Creative and commercial innovations in hi-fidelity stereo, broadcast television, videotape, and satellite technologies, conceived in the 1940s, ignited a frenetic pace of social change through the 50s, 60s and 70s, simultaneously shattering and shaping modes of communication and expression. From the 80s into the present millennium the electronic age burst through to the digital age, advancing in previously inconceivable directions at blinding speeds and opening entirely new terrain for creative explorations. Today, motherboards, video games, cellular communications and smartphones continue to transform ideas of historiography, representation and access — not to mention velocity and possession — both publically and privately, locally and officially.

The rebellion against semblance, art’s dissatisfaction with itself, has been an intermittent element of its claim to truth from time immemorial.

>> Theodor W. Adorno, 1970

Artists have encountered such technological leaps with impunity and within them, shaped an extraordinary rebellion that continuously redefines how we imagine, receive and understand our time. Media Art realizes Adorno’s confrontation with semblance. It is one that defies and redefines the formerly fixed boundaries of traditional disciplines such as painting, sculpture and photography; even theater, performance and literature, and one that challenges all previously settled conformities of expression. This fearless embrace of contemporary materials is a striking disclosure of the ambitions it engenders. It is either optimistic or insidious, or both. It fuels a range of aesthetic styles, formal practices and conceptual engagements with technology that together empower artists to confront the complex histories of the present and to inspire new futures.

The essayist Paul Virilio identified the “integral accident” as an irony intrinsic to invention. Basically, when you invent something, you also invent its accident. If you invent the train, you invent derailment. Harnessing electricity simultaneously introduced electrocution. “Every technology carries its own negativity, which is invented at the same time as technical progress.” Accidents are inventions in their own right. A compelling perspective can be assembled from this framework, expanding far beyond the limited scope of technology alone, but describing an influence technology asserts in social, civic and cultural spheres. It composes a mesmerizing conspiracy of events that portray (or betray) the most detailed contours of any contemporary renderings of history or culture, perfectly situated for the information age.

It is interesting to consider Virilio's "integral accident" in relation to the evolutions of media and the history of art, or more specifically media art and technology. Technological developments have accompanied and distinguished progress, contributing both triumphs and catastrophes that define our shared experience. The internal logic of these technologies can be simplified as an exercise in distilled contrasts. Celluloid film is illuminated through densities of black and white. Analogue video is recorded in waves of peaks and valleys. Digital media is coded in binary 1s and 0s — on or off. One instance is used to articulate the tendencies of another. And technology has maintained this state of progressive flux since its inception; ironically 'colluding with' and 'evolving in' parallel events of unforeseeable but intricately intertwined contradictions. The sublime invention of television was immediately coopted by political and pornographic manipulations. And then, there is atomic energy andthe atom bomb, Woodstock and Altamont, free love communes and the Manson Family, Spielberg's E.T. and Reagan's Star Wars defense plan, German Re-unification and China's Tiananmen Square Massacre, (or the Berlin wall comes down followed by erecting walls elsewhere like Texas and Jerusalem). Artificial intelligence contains the doomsday machine. In today's media scape, these contrasts are compounded in the form of mass media megalopolies and narrowcasting social media. Think News Corp and Google versus SnapChat and Instagram. More acutely, we live with the NSA and Anonymous. Media actors, channels and languages develop in tandem with the events they possess, define and propagate, even while they are occurring. OJ Simpson became famous for running, both on the football field and on the 405 Freeway, both of which were broadcast live and both of which intensified his presence in popular consciousness, celebrated and reviled. And the potency of such contradictory occurrences is amplified through the very technological promise that invests them with such a concentrated speed of distribution. The Internet trumpets equality as a democratic tool for breaking down all hierarchies, but also exists as a panopticon of surveillance and totalitarian manipulations. Each of these instances technologically entangles the ideals we optimistically romanticize with calamities we could scarcely imagine. It is within this complex media existence that experience itself becomes fantastically difficult to pry apart or interpret; the narrow and broad, near and remote, real and illusory, minute and gigantic, the live and the recorded.

Such a schizophrenic reading is perhaps an oversimplification. Each dramatic extreme is what garners the most attention, or the only attention. The repetitive whiplash snaps off most of the nuance, loosed in the fray. But these are the consequences of an unrelenting competition among images and for recognition. And in a cultural terrain largely colonized by media and technology, it precisely locates the frames of engagement among media artists.

_MEDIA ART

These extremes also identify media art’s complicity in confronting the modernist metanarrative as a form of “progress,” and challenges ideas of a single history plodding along in any meaningful way towards fulfillment. Here, it enables an artistic misdirection as both appropriation and repurposing images and technologies become strategies for artists to liberate themselves with a lightning like intensity.

Technology’s proximity to mass media consumerism — which once complicated its relation to the arts — now makes it a curious bedfellow to artistic practice. That transition, from unsavory to seductive, marks a critically important new dimension. As John Hanhardt points out in his 1995 essay “Video/Media Culture of the Late Twentieth Century”,

[...] Video as a technology and as the basis of a complex aesthetic discourse has played a key role in both facilitating and critiquing the circulation of media images and ideas between the worlds of art and popular entertainment. Since the 1960s the rapid expansion of the cultural industries of movies, television, music, and radio has been paralleled by an attitude toward mass media that is undergoing a transformation as artists moved from a modernist disdain of mass entertainment to a postmodernist appropriation and transformation of popular culture as a new discursive strategy.

While Hanhardt and Villaseñor were writing specifically about video, the thinking can be expanded to include all contemporary media art and better define its vocabulary and flexibility as a medium. In terms of media, art is being rendered from a now loosened framework in which history is no longer seen as a source of authority, but a source of virtual and reflexive material.

_DEFINITION, DISTRIBUTIONS

Media art has evolved so rapidly, enveloping so many disciplines with such a concentration of perplexing materials that it begs constant rediscovery. Its definition is in constant flux, making it notoriously difficult to place, but it is also revealing. Film and media art engage a diverse range of emergent and receding technologies, including filmmaking and projection, digital and computer graphics, analogue and computer animation, web or internet art, virtual and augmented reality, interactive art and video games. It also includes computerized robotics, 3D printing, biotechnologies and artificial intelligence. Each innovation and its resulting, recombinant affect are un-fixed by new practical, sociological and conceptual underpinnings that challenge traditional modes of expression. Media Art’s rebellious character (coupled with varying levels of intention and self-awareness) situates it as a mongrelized art form somewhere between the plastic arts of drawing, painting and sculpture, and the temporal arts of theater, dance and music. Where most contemporary art is preoccupied with concerns about medium — defining a medium’s specificity or what makes it unique - media art blurs the focus on technological media and distinguishes itself in a critique of the social and creative exchange itself.

Rather than chronicle a progression of inventions and innovations, the vibrant exchange between media artists and electronic technologies, as well as their historical reverb, alludes to a non-linear telling. There appears no secondary or first but a flexible distribution that looks both forward and backward. This novel panoramic is perhaps best approached as series of nomadic arrangements relating conceptual and material operations on the surface of a deeper “media history in art”. This exhibition is not an essentialist reading of contemporary art, or even media art alone. But as an introduction to the materials and practices, it can guide a process of simultaneous reflection and activation that provokes a better understanding of media art’s character and maturity as a mode of expression among artists.

_FILM

Cinema and moving image film as we know them are late 19th century inventions. Professional studio cameras and cinema’s 35mm film standard are large, unwieldy contraptions. They are quite expensive to operate. Making moving images was exceedingly difficult without professional studio assets and production assistants. It wasn’t until the early twentieth century that the 16mm film gage was created as an inexpensive, alternative moving image format intended for amateur use. Its portability and ease of operation made for early adoption by scientists, educators and the military. The broadcast industry turned to 16mm film to capture live news events in the field for relatively quick playback in and broadcast from the studio. At the outbreak of the Second World War, 16mm film’s ease of distribution was championed by the US government as a means to educate soldiers; and as a result, trained soldiers in the technical processes necessary to create films and animations. The US military contributed to a large network of professionally trained filmmakers, who, as the war ended, returned from a theater of war with a fantastic set of creative and technological skills. Years on, film’s official and political origins have been reoriented among avant-garde filmmakers, animators, and artists seeking to identify the cultural margins of the moving image and define a practice novel to themselves.

_MUSIC

Classical music is a recurring springboard for radical interventions in the performing and visual arts, and musicians are often the first to challenge tradition. Representing the political and social superstructure of "high culture", rigid instrumentation and traditional compositions of orchestral music have repeatedly been targeted by a creative class seeking to disrupt conventions and repossess modes of expression. At the turn of the 20th century, a "crisis of tonality" was identified as composers and musicians began to systematically press the edges of the score. From sophisticated harmonics and complex chords to singular instruments and minor notes, composers assembled and deconstructed nearly every aspect of music in a conscious and deliberate attempt to redefine musical arrangements from within the medium. The influential composer Arnold Schoenberg confronted the crisis and conceived of the "emancipation of dissonance" as a strategy to release composers and audiences from their harmonic bonds. Another composer, George Antheil, removed musicians altogether and wrote scores for mechanical pianos, airplane propellers and sirens, to be performed "as beautifully as an artist knows how". And then there was John Cage, who approached the piano, lifted the lid, and sat motionless in silence for 4 minutes, 33 seconds. These provocative responses to tradition in classical music would prove a watershed for generations of creative minds armed with the electronic tools of mass media. These tools brought the recordability of sound, giving physical dimension to time itself — found or created — and shaping time and sequence into objects during performances, events or happenings. The territory between hi and lo culture further became valuable ground. Many artists moved to subvert hi-fidelity recording technologies and disrupt slick corporate productions, in some cases abandoning them altogether, as deliberate political and ideological tactics. It was a means to repossess cultural meaning and invest the composition, score, and staged performance with new conceptual importance.

_TELEVISION AND VIDEO

Live distribution and corporate broadcast mechanisms established by radio were built over decades, precipitating those used for television. But the sudden and accelerating televisual saturation of American culture has not been subtle. Its impact was immediate and noticeable from the outset. During the Second World War there were only about 40,000 TV sets in use, most of which were located in and around New York City. Tellingly, that was where the majority of broadcast stations were also located. By the end of the decade there were an exponential 10 million. By 1959 that number had grown to an estimated 70 million. The television set transformed not only the structure of the American home through the introduction of new furniture, but also the daily routine and economy of family life. In the 1960s, televisions sets became the most common purchase for the home, surpassing the piano. Newsreels beamed the front line directly into the living room. Live broadcasts of international events evaporated geographic and celestial distance in dramatic ways, suggesting a new realization of our place in the world. Consider watching the news from Dallas while sitting in Boston, or the Moon Landing from Hollywood. Large television corporations took shape and began producing new mass media networks, fed by commercial advertising, focused on cultural and entertainment programming, and assuming a passive audience.

The reach and influence of this new medium was immediately recognized on a number of fronts. The federal government seized regulatory controls and licensed bandwidth to broadcasters in exchange for educational and news programming. The federal government also sought to empower communities through the National Endowment for the Arts. In addition to funding traditional artists, the NEA funded artists’ access to the burgeoning mediums of film, television and video by supporting and promoting both individuals and collectives. The intent was clear, “While no government can call a great artist or scholar into existence, it is necessary and appropriate for the federal government to help create and sustain not only a climate encouraging freedom of thought, imagination and inquiry, but also the material conditions facilitating the release of this creative talent.” This principal enabled individual communities to demand greater public access and create community network stations that could be populated with locally sourced and created programming. Consumers of television were also now newly minted producers, further spurring developments in video and sound systems that empowered local voices and providing a semblance of ownership over representation.

_COMPUTERS

While our interaction with computers today may mostly occur from social or consumer perspectives, through Amazon, Wikipedia, Google Maps and video games, the computer’s origins are inextricably linked to the military industrial complex. Mainframe computers and the languages articulated for them are the invention of research centers largely funded by the United States Army and the Pentagon. The ENIAC machine, the first electronic computer system, was created in the mid-1940s to calculate firing tables for artillery. But the computer’s political and creative potentials were immediately coopted to predict democratic elections, like Dwight D. Eisenhower’s 1952 election victory, or code videogames such as Alan Turing’s computer chess programs in the late 1940s and 1950s. In the late 1960s, the Department of Defense was further developing ARPANET (fore runner to the world wide web) as a means to decentralize authority and safeguarding information in response to geopolitical tensions with the Soviet Union during the cold war. The thinking was that spreading information out would make it less easily destroyed, similar to the depository library system. Simultaneously, commercial companies like the Western Electric Company and American Telephone and Telegraph Company (AT&T) were funding artist residencies at Bell Telephone Laboratories, Incorporated, more commonly referred to as “Bell Labs”. As military computers envisioned the triggering of a nuclear apocalypse, artists were envisioning an alternative, or in the least, a more human application.

While computer technology and geopolitics have become far more complex since the 1960s, many of the same forces are still at play, only amplified by the computer's global reach into nearly every culture and industry. The computer's shape-shifting roles in enabling catastrophe and cataloguing 3.7 billion cat videos is matched by the significant part it plays in contemporary arenas of commerce, and reflected again in one of its principal economies, that of video games. The videogame 'industry' has too been an exercise in conformity and counterculture in a way that parallels the history of television, encapsulating commerce, popular entertainment and individual creativity. Systems engineered for the serious business of big data computation were spun-off into arcade culture where gaming machines included a cup holder for your beer and an ashtray. The first computer arcade game was Computer Space, a multi-directional, extra-terrestrial shooter. This marked the beginnings of a consumer video game industry with a projected annual value of $91 billion worldwide. By comparison, the book industry generates approximately 60 billion. Mirroring television, video game development and distribution was once the sole domain of corporations, but was soon thereafter repurposed by creative programmers and artists seeking to subvert those corporate monopolies, establishing an independent gaming community that authors alternative works well outside of the industry standard.

Michael Mansfield

Curator of Film and Media Art

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Online Gallery

Artists

Nam June Paik (1932–2006), internationally recognized as the "Father of Video Art," created a large body of work including video sculptures, installations, performances, videotapes and television productions.