Born 1960 in Larchmont, NY

Lives and works in New York City

Walton Ford has been depicting animals for as long as he can remember. Although immediately reminiscent of traditional natural history painting, Ford’s images double as complex allegories, blending depictions of nature with historical events and sociopolitical commentary. Over the last twenty years, Ford has created more than one hundred paintings and prints with birds as the primary subject.

Image Gallery

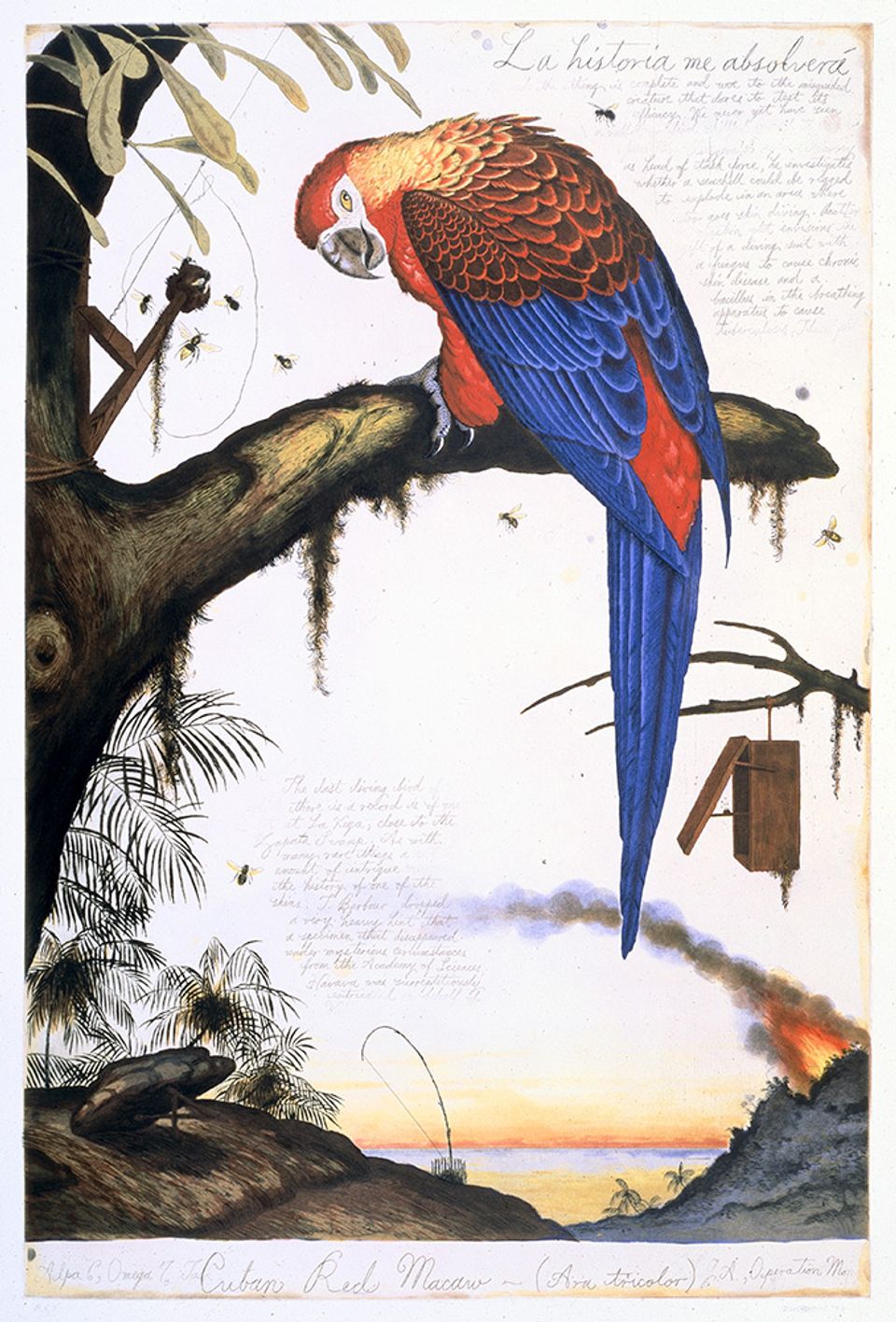

Walton Ford, La Historia Me Absolverá, 1999, color etching, aquatint, spit bite, and drypoint on paper, 44 x 30 in., Courtesy of the artist and Paul Kasmin Gallery, Image courtesy of the artist and Paul Kasmin Gallery

La Historia Me Absolverá features the now-extinct Cuban red macaw as a personification of Communist leader Fidel Castro. The title, which translates as “History will absolve me,” references the closing lines of a speech delivered by Castro before being jailed in 1953 for the attack on an army barracks. Castro’s subsequent release and rise to power led to numerous attempts on his life. Ford represents these threats as flies and snares surrounding the defiant macaw. He portrays the bird as a dying breed—like Castro himself—gripping tightly to a broken tree branch that might symbolize Cuba’s beleaguered state or Castro’s legacy.

Walton Ford, Eothen, 2001, watercolor, gouache, and pencil and ink on paper, 40 x 60 in., The Cartin Collection, Image courtesy of the artist and Paul Kasmin Gallery

Made in the wake of 9/11, Eothen is one of Ford’s most brooding and enigmatic paintings. The title is a Greek word meaning "from the east" and also a reference to a nineteenth-century travel account of the Ottoman Empire. According to the artist, the besieged peacock represents the conflicts waged on Middle Eastern soil over the centuries. The bird’s smoldering train might also reference the ancient belief that peacocks were immortal. It is unclear if Ford’s bird is rising from the ashes or being devoured by them. In either case, it is a powerful commentary on death, resurrection, and geopolitics.

Walton Ford, Compromised, 2002, color etching, aquatint, spit bite, and drypoint on paper, 44 x 30 in., Courtesy of the artist and Paul Kasmin Gallery, Image courtesy of the artist and Paul Kasmin Gallery

Walton Ford, Falling Bough, 2002, watercolor, gouache, and pencil and ink on paper, 60 1/2 x 119 1/2 in., Private Collection, Image courtesy of the artist and Paul Kasmin Gallery

In Falling Bough, Ford depicts one of the great migratory events of the nineteenth century as a nightmarish scene of overpopulation and self-destruction. A branch laden with passenger pigeons is momentarily lifted skyward as it splinters beneath the weight of the snaking mass. Scenes like this were well documented by hunters and naturalists alike. John James Audubon witnessed the astonishing sight while traveling through Kentucky. He wrote, “The pigeons, arriving by thousands, alighted everywhere, one above another, until solid masses were formed on the branches all round. Here and there the perches gave way under the weight with a crash, and, falling to the ground, destroyed hundreds of the birds beneath.”

Walton Ford, Madagascar, 2002, watercolor, gouache, and pencil and ink on paper, 120 x 60 in., Private Collection, Image courtesy of the artist and Paul Kasmin Gallery

The Great Elephant Bird, Aepyornis maximus, lived on the island of Madagascar until its extinction in the late eighteenth century. There are no accounts of what the bird actually looked like, but skeletal remains suggest it was ten feet tall and may have weighed nearly half a ton. Like many island species, the elephant bird had few predators until settlers arrived on Madagascar and began hunting it and pilfering its enormous eggs. In Ford’s image, the perpetrators appear to be pirates. The hobbled bird lets out a squawk as a chick calmly watches the assault. In the background, scenes of piracy and exploitation allude to man’s lasting impact on the fragile island ecosystem.

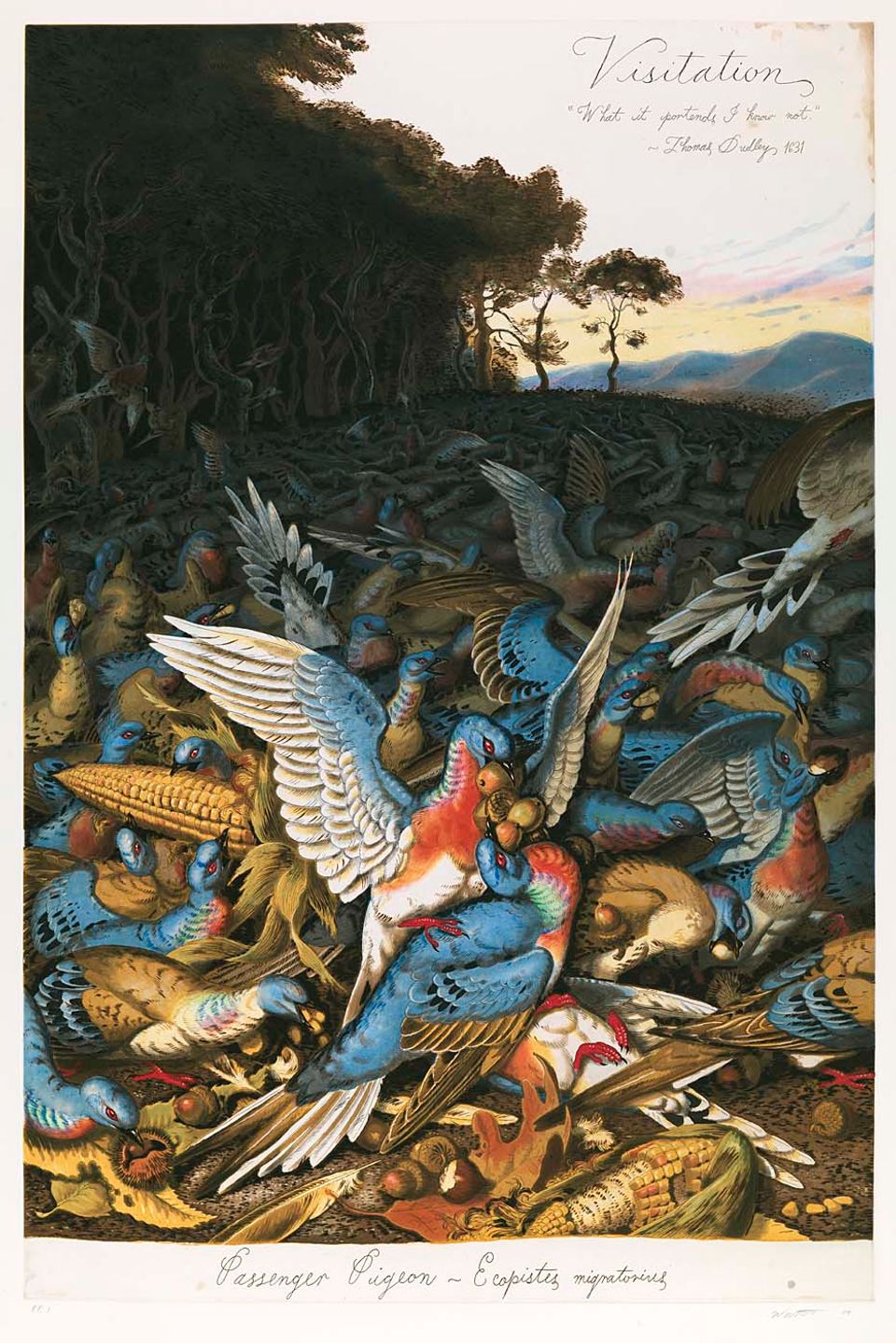

Walton Ford, Visitation, 2004, color etching, aquatint, spit bite, and drypoint on paper, 44 x 31 in., Smithsonian American Art Museum, Museum purchase through the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment, 2010.3

In Visitation, a large flock of passenger pigeons gorge themselves in a field strewn with fruit and nuts. Ford’s scene recalls a written description by Audubon, "Whilst feeding, their avidity is at times so great that in attempting to swallow a large acorn or nut, they are seen gasping for a long while as if in the agonies of suffocation." The birds’ ravenous feasting on the bounty of the land could symbolize the profligate exploitation of natural resources perpetrated by European settlers in the New World, which ultimately led to the extinction of the passenger pigeon. Ford also notes that the image alludes to the human tendency of blaming victims for their own destruction.